How David McGlynn Found His Home in “Worry”

Like many in the publishing industry, I was stunned two weeks ago when I read about the closing of SMU Press—even though the university has been speaking of this as a “suspension of operations” rather than a full termination, the apparent suddenness of the move, as well as the confusion it has already spawned about both the extensive backlist and the books that were supposed to come out this year, have an air of irrecoverability about them. Folks are doing what they can to persuade SMU to keep the press alive, and I wanted to do what I could to testify to its value—the contributions it has made to the short story genre have been of particularly consistent excellence. With that in mind, I worked on rounding up some of the great short story writers SMU has published and introducing them to you.

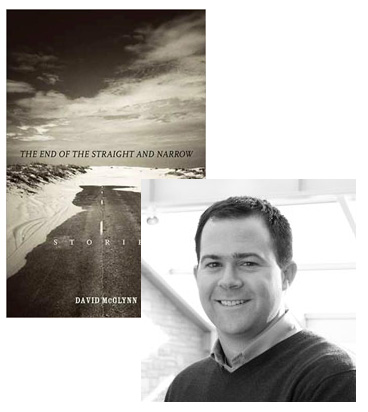

Some of them, like David McGlynn, have chosen to write about other authors published by SMU Press. But after you’ve read McGlynn’s take on Scott Blackwood, be sure to read his own collection, The End of the Straight and Narrow. He writes with enormous grace about people dealing with the tensions between their evangelical faith and the pressures of the world—you may not always agree with their actions, but you can’t write them off, either, and you can’t not care about how their stories turn out.

I grew up in Houston, Texas, but moved away the week I turned eighteen, vowing I’d never live there again. The entire state seemed, in my desperation to flee, a haven of rednecks and rockfaces, so utterly boring and suburban that nothing interesting could come from there. Surely no good stories came from there. My parents and grandparents had two books on their shelves I recognized as unmistakably Texan—James Michener’s Texas and Larry McMurtry’s Lonesome Dove, two big tomes my mother used to hold the skinnier books in place. Their names were the only two I knew, and given the size of both books, I was content to leave them quietly on the shelf.

It wasn’t until I was in graduate school and beginning to work on the stories that would eventually become The End of the Straight and Narrow that I found myself once again interested in Texas. My mother lived in Austin, but even still, I didn’t visit more than once a year, and only for a few days at a time. I found myself in a quandary, writing about Texas but feeling cut off from its people and culture. I began casting around for something to read.

Asking for names of Texas writers is sort of like asking for examples of famous rock bands from Georgia. Just as most people can probably name the B-52s, REM, and the Indigo Girls, most readers can rattle off that, in addition to McMurtry and Michener, Donald Barthleme was from Houston, Sandra Cisneros is from San Antonio, and Cormac McCarthy lived in El Paso. I read those writers with enthusiasm, but also with detachment; in each of them, I saw a Texas I recognized but didn’t belong to. Both McMurtry and McCarthy tended toward a Texas without the seemingly endless sprawl of billboards and big box stores and car dealerships, the Texas I knew and remembered. I needed a wider net.

17 May 2010 | selling shorts |

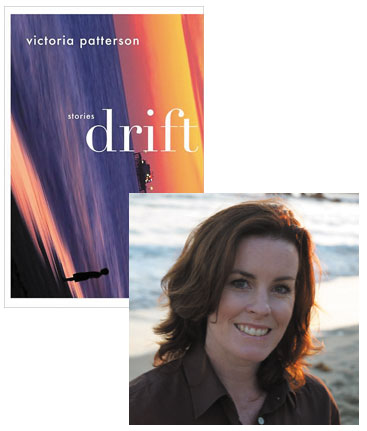

Victoria Patterson on Busch’s “Ralph the Duck”

When I started working for Houghton Mifflin Harcourt a few weeks ago, I reaffirmed my commitment to introducing you to books from other publishers; I didn’t want (and I’m sure you don’t want) Beatrice to become simply an extension of my day job. That said, every now and then there’s going to be an HMH title that I can’t help but write about, and today it’s Drift, one of three short story collections nominated for this year’s Story Prize. (And as long as we’re in full disclosure mode, I was a judge for that prize a few years back.) Patterson’s stories show us Newport Beach from the perspective of characters who live in its margins, people we might otherwise miss, blinded by the glare of Southern California’s coastal mystique. She’s already made some appearances in the literary blog world, including a guest essay at The Millions an an interview at The Elegant Variation, and in this essay she tells us about learning everything she could about one story’s author—having just missed the opportunity to tell him how much that story had meant to her.

In February 2006, I read Frederick Busch’s “Ralph the Duck” for the first time. “Ralph the Duck” is told through the first person voice of Jack, a 42-year old security guard at a private Northeastern college, taking advantage of the free classes offered to employees there, married to Fanny, an emergency room nurse, both of them mourning the death of their infant daughter. Tender and full of loss, moving through the murky region of despair, and imbued with a sense of high stakes, here was a story that played it straight, laid back the skin and cut to the bone. Later, I read that Antonya Nelson called it “a short story masterpiece.”

“I woke up at 5:25 because the dog was vomiting.” So begins Jack’s narration. The dog, we learn, “loved what made him sick.” Jack swears he can hear his wife blink because of “the damp slash of lash after I have made her weep.” Their marriage is suffering—faltering—from grief. They go to the movies and Jack “fell asleep, and I’m afraid I snored.” Jack’s voice is sad and funny, wise and knowing, aware of his shortcomings. When he sets out to save a local teenaged girl, he conflates it with the loss of his own child (“She better not die this time”).

20 January 2010 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.