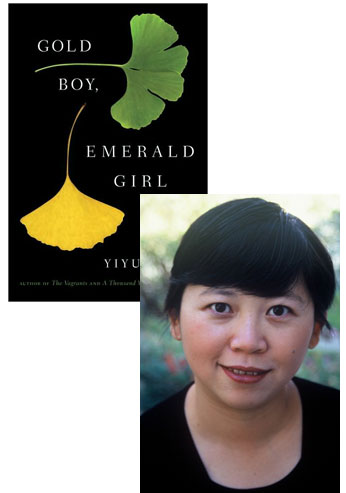

Yiyun Li: A Razor-Sharp V.S. Pritchett Story

Emotional isolation and making the best of what life’s put in front of you are two themes that get a serious workout in Yiyun Li‘s new short story collection, Gold Boy, Emerald Girl, from the opening novella, “Kindness,” to the eponyous short story that ends the volume. The stories might seem cold and distant at first, but give them time to sink in—and they’ll probably wind up sticking with you much like the tale told to the narrator of the short story Li’s chosen to write about for Beatrice.

A couple years ago I taught a story by V.S. Pritchett (an under-read master of short stories, whom, in my opinion, should be read along with Chekhov and William Trevor) in a course of reading short stories to seven undergraduates. The story is titled “You Make Your Own Life.” After my opening, there was a moment of silence, and a student raised his hand. “Professor, we know you love sad stories, but this is unbearable! This is too much! Where’s the hope?”

(Off-topic: “where is the hope” seems to be a question asked often of me. Growing up in a different place, my answer is that as long as one can read and write about bleakness, as long as one can understand it, the world is still hopeful; it would become a crueler and bleaker place when hope puts on a costume of deception and propaganda, which happens only too often.)

The story is short—six pages, written in first person. It opens when the narrator, waiting in a small town for a train that was not to come, spots a barbershop and decides to have a haircut. Other than this one impromptu decision, we learn nothing more about the narrator himself for the rest of the story. But what propels a man to enter a barber’s shop when his should be waiting for the train to leave the town? Already it is described as “a dead place,” and “ten miles from this town the skeletons of men killed in a battle eight centuries ago had been dug up on the Downs.”

17 September 2010 | selling shorts |

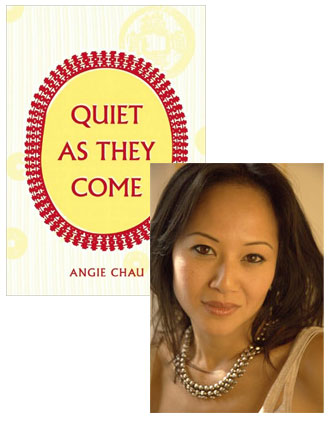

Angie Chau Thinks About “Every Little Hurricane”

Quiet As They Come, the debut collection by Angie Chau, gives us multiple perspectives on an extended family of Vietnamese immigrants, beginning five months after their arrival in San Francisco, as eight-year-old Elle recalls a Fourth of July during the summer all twelve of them lived in the same three-bedroom house. One of Elle’s aunts, Kim, becomes the focus of the next story, then her mother, Huong, then her father, Viet, and so on, before returning to the adult Elle in the final story. The shifting points of view give us access to a variety of experiences and insights into how we can still feel out of place even after years of living in the same location. In the story she’s chosen to write about for Beatrice‘s “Selling Shorts” series, Chau touches upon similar feelings of existential alienation and a child’s-eye view of an unsettling world all too close to home.

I relish personal stories. In life, I love listening to secrets, confessions, tidbits of gossip. In fifth grade I started a game with my two best friends called True Confessions. My best friend’s father was a jazz musician and had a sound proof studio behind the house. We stood on the make shift stage, turned on the microphone, and announced the one “true confession” that we would never admit out loud at school. The game didn’t last long. I don’t think my friends were as interested in this same sense of exposed purging. To this day, however, I am a good secret-keeper. Friends, neighbors, and coworkers always come back to tell me more.

In fiction, I crave the same kind of intimacy. I want it to be our world, yours and mine, alone. I want to feel like you trust me enough to reveal something untold to others, something you are uncomfortable about. And maybe through your courage, your vulnerability, through your telling of it, I get to admit things I didn’t have the words for before. I can acknowledge a shared fear or shame, I can ask questions I’ve never asked before.

A story that has inspired me is Sherman Alexie’s “Every Little Hurricane,” from The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven. Its technical brilliance, dark humor, and sweet sadness, distill a world in all its complexity into one night. Because I had never encountered Spokane Indians or any Native Americans in literary fiction, the story feels otherworldly, both refreshing and haunting. I was immediately struck by how these people were both absolutely foreign, yet somehow familiar.

14 September 2010 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.