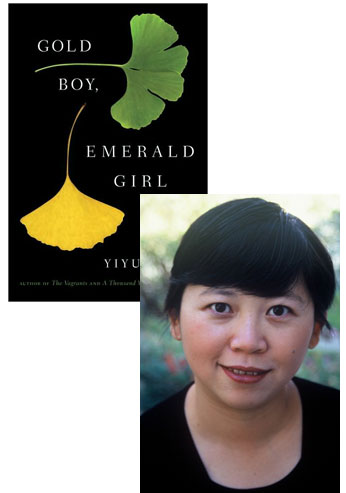

Yiyun Li: A Razor-Sharp V.S. Pritchett Story

Emotional isolation and making the best of what life’s put in front of you are two themes that get a serious workout in Yiyun Li‘s new short story collection, Gold Boy, Emerald Girl, from the opening novella, “Kindness,” to the eponyous short story that ends the volume. The stories might seem cold and distant at first, but give them time to sink in—and they’ll probably wind up sticking with you much like the tale told to the narrator of the short story Li’s chosen to write about for Beatrice.

A couple years ago I taught a story by V.S. Pritchett (an under-read master of short stories, whom, in my opinion, should be read along with Chekhov and William Trevor) in a course of reading short stories to seven undergraduates. The story is titled “You Make Your Own Life.” After my opening, there was a moment of silence, and a student raised his hand. “Professor, we know you love sad stories, but this is unbearable! This is too much! Where’s the hope?”

(Off-topic: “where is the hope” seems to be a question asked often of me. Growing up in a different place, my answer is that as long as one can read and write about bleakness, as long as one can understand it, the world is still hopeful; it would become a crueler and bleaker place when hope puts on a costume of deception and propaganda, which happens only too often.)

The story is short—six pages, written in first person. It opens when the narrator, waiting in a small town for a train that was not to come, spots a barbershop and decides to have a haircut. Other than this one impromptu decision, we learn nothing more about the narrator himself for the rest of the story. But what propels a man to enter a barber’s shop when his should be waiting for the train to leave the town? Already it is described as “a dead place,” and “ten miles from this town the skeletons of men killed in a battle eight centuries ago had been dug up on the Downs.”

Once in the barbershop, the narrator serves entirely as ears and eyes for the readers. In the barber’s chair is a sickly-looking young man, grim as the town seems to be. But wait, there’s also the barber himself, who, despite not speaking to his customer, is efficient and dutiful and contented with his job. “A peculiar look of amused affection was on his face as he looked down at the soaped head.” And when the customer was gone, “the barber was smiling to himself like a man remembering a tune.”

A happy man! As one can easily make a happy man talk, the narrator, with a few questions, is able to make the barber tell a triangle love story. But is it the narrator’s accomplishment? The more the barber talks, the more the readers realize that no, the narrator could be any stranger from out of town—the barber has been waiting for the moment to recount his tale of triumph all along. The narrator only surrenders himself when loneliness drives him into the barbershop.

And the story of triumph in love—how the barber beat his best friend to marry a girl they both courted—is an old story, and the barber, a good storyteller as Pritchett himself was, does not dwell on his success but more on his friend’s deterioration in his lost battle. First he tried to poison the barber, and when that failed, the friend sent the couple “the best man’s present” by slitting his throat, but that effort failed, too.

“Funny present,” the barber said. The couple lived happily ever after, with the friend coming to visit all the time, playing with their children. “The only thing is he doesn’t like shaving himself now,” the barber said of his friend. “I have to go over every morning and do it for him. I never charge him.”

The story is over. It’s time for the narrator to exit the barber shop. A short story is always like that, showing you the way out before you are ready, closing the door behind you, but only when you hurry down the platform to catch the train do you realize that the story has taken part of you hostage: the barber in with his bemused smile; the slowly-dying friend who feels the touches of the barber’s hands every day. “Where’s the hope?” bemoaned my young student, and not knowing how to make him feel better, I gave him a very American answer. “The hope,” I said, “is with the title of the story—You Make Your Own Life.”

17 September 2010 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.