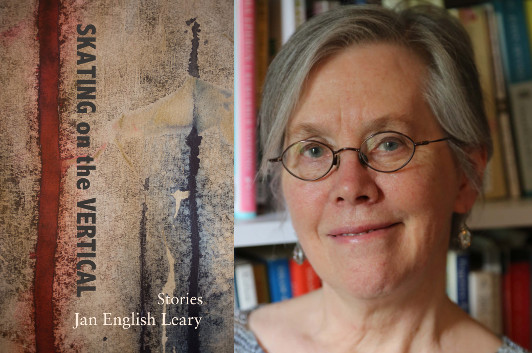

Jan English Leary on Antonya Nelson

photo: John Leary

Many of the protagonists in Skating on the Vertical, the debut short story collection by Jan English Leary, are women on the edge: A young teacher frustrated by a system rigged against one of her immigrant students; a mother desperate to persuade her teenage daughter not to have an abortion; women struggling not to relapse into self-destructive habits in the face of stress. Nobody comes out the other side “fixed,” but they find the strength to push through just the same. In this guest essay, Leary talks about a writer whose emotional depths helped her realize that she, too, not only had stories to tell but could find the means within her to tell them.

I came late to writing fiction, later than most writers. I was in my mid-thirties with two small children and a full-time job teaching French. I’d always been an addicted reader and a lover of language, but it never occurred to me that I could write fiction. I could write analytical essays about other people’s work, but I couldn’t imagine generating stories myself. It was motherhood that brought me to writing, that made me want to explore the intricacies of human relationships through stories.

Back when I was in high school, I read Salinger’s Nine Stories, and my eyes opened to the magic of short fiction. I started reading my parents’ issues of The New Yorker and came to know the work of Eudora Welty, John Updike, John Cheever, and Isaac Bashevis Singer. As a young adult, I loved the work of Ann Beattie, Alice Munro, Tobias Wolff, and Lorrie Moore. But it wasn’t until the early 1990s, after I’d been writing fiction for a few years myself, that I encountered the work of Antonya Nelson in The New Yorker and The Best American Short Stories. In her work, I knew I’d found someone who spoke to me not only as a writer but also as a woman and a mother.

Nelson writes about the power of maternal love, but she doesn’t shy away from allowing her characters to have moments of doubt, regret, even rage and to make big mistakes. She is unflinching in her honesty. No one does a better job than Nelson of populating her stories with families that are broken and cobbled together but bound by fragile yet fierce love. Sometimes these are biological bonds; sometimes they are alliances made of marriage. And with Nelson, there’s always a complicated family web: ex-spouses, in-laws, step-children. But what endures are the bonds of familial love.

11 December 2017 | selling shorts |

Laura Hulthen Thomas Plays a Long Game

photo: Ron Thomas

Hey, if you’re going to be in Ann Arbor, Michigan, on August 21, 2017, you should swing by the University of Michigan campus in the afternoon, because Laura Hulthen Thomas will be reading from her new story collection, States of Motion, along with Linda Gregerson, Mike Ferro and Debotri Dhar.

And if you’re not going to be there, you should track this book down, because these are some fantastic stories. I’m particularly enamored of the way Thomas goes all in on her narratives, drawing out the main action so expertly that you want to dwell longer in these worlds, dive deeper into their backstories. One of the most effective ways she does that is to hit her characters with multiple stressors, like the woman in “State of Motion” who’s trying to coach her son through a school competition while sorting out her extramarital affair with the janitor, or the driving instructor in “Adult Crowding” scrambling to cope with his dying mother while taking two argumentative teens out on a driving lesson. In this essay, she explains how she came to love stories that aren’t so short, as both a reader and a writer.

Whenever I’m asked, “Why do you write short stories?” I’m honor-bound to point out that I’m not a short story writer! The stories in States of Motion clock in at around thirty pages, with a couple of longer pieces, too. Why am I so devoted to the longer story at a time when readers and writers are having so much fun reimagining storytelling through micro-fiction, prose-poems, posts and tweets? Literary evolution has taken us from the days when Dumas was paid by the word for The Count of Monte Cristo to Amy Hempl’s or Etgar Keret’s radical narrative slimming. Readers’ habits trend towards brief, intense portraits of situation and experience, easy on the dialogue, enough with the navel-gazing already.

21 August 2017 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.