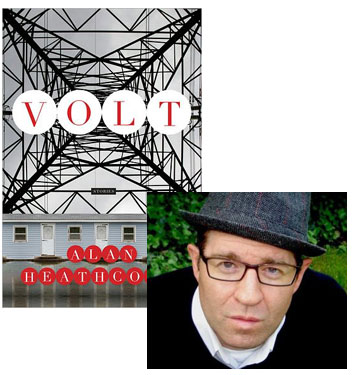

Alan Heathcock, Carried Off “Upon the Sweeping Flood”

The stories in Alan Heathcock‘s debut collection, Volt, are compellingly stark: Unable to deal with the emotions churned up by the accidental death of his son, a man simply wanders off, until he winds up in a new community where he earns money withstanding other people’s physical assaults; a sheriff goes to extraordinary lengths to preserve the tranquility of her community, and then a flood forces her to revisit her actions. The violence in Heathcock’s stories takes on a surreal quality, and yet for all its unworldliness it doesn’t lose its visceral immediacy. In this guest essay, he explains how he’s been inspired by a master of such tales.

I must steel myself. Must be brave. I must not look away. It’s hard and self-conscious and everything in me tells me I’ve gone too far. What will they think of me? What will they think if they know my mind? This is my dilemma, being a writer. I’m a naturally private man, yet the written word eventually becomes very public, judged, interpreted, and for that I try to be brave, to not falter.

I need help. When I am at my weakest I read the work of authors who’ve gone far beyond me, ahead of me, who are revered. In this regard, Joyce Carol Oates is the bravest of writers, one of the fiercest champions of unflinching truth I know.

I own an old ragged paperback of the story collection Upon the Sweeping Flood. The pages are yellow and brittle. On the first page, before any of the stories, is a quote from Oates: “I am concerned with only one thing, the moral and social conditions of my generation.” Just like that. So easy, so focused. My problem is clear. I am distracted, focusing on many things, while her concern is distilled into a single sentence. And oh how she pays out that focus.

The first time I read the title story, I was sitting in a condo on the fifth floor of a building in Chicago, Illinois. I remember it was fall, probably October, and I put the book down, trembling a bit, and stared for a long time into the golden tops of the locust trees outside my window. I was a budding writer then, and remember reflecting on my own work and thinking something like, “You’re not even close. Not even in the ballpark yet.”

13 April 2011 | selling shorts |

Mike Sacks and His Naked Admiration

There’s a copy of Mike Sacks’ Your Wildest Dreams, Within Reason somewere in this apartment, and if I could track it down I would quote for you verbatim from the piece within it that had me laughing out loud on the 7 train, especially since it was about the 7 train, at least glancingly. Oh, wait, that particular joke is online: “Kama Sutra: The Corrections.” (Note: Totally NSFW, which made reading it on a rush-hour subway train a bit of a challenge; eventually, I flipped back to “The Rejection of Anne Frank,” which Sacks co-wrote with Teddy Wayne; it’s actually probably even more outrageous, but at least not visually so.) And then there’s “IKEA Instructions,” which just flat out reduces both me and my wife to tears of laughter… Anyway, suffice to say Mike Sacks is my type of humor, and in this essay, Sacks pays tribute to one of his favorite humorists.

David Sedaris is always mentioned by both readers and writers as being one of their favorite humorists, and for good reason. Technically, I find him one of the best writers currently working, in humor or any other genre. All of his books are top-notch, but for the sake of this mini-essay, I’m going to mostly concentrate on his 1996 book Naked. And I’m going to talk about two things that impress me about his writing: his endings and his dialogue.

First, endings. Sedaris is a master at creating endings that end on just that perfect note of pathos and optimism (not an easy combination). This ending is from his story “Ashes,†a beautiful piece about the loss of his mother:

“Our mother was back in her room and very much alive, probably watching a detective program on television. Maybe that was her light in the window, her figure stepping out onto the patio to light a cigarette. We told ourselves she probably wanted to be left alone, that’s how stoned we were. We’d think of this later, each in our own separate way. I myself tend to dwell on the stupidity of pacing a cemetery while she sat, frightened and alone, staring at the tip of her cigarette and envisioning her self, clearly now, in ashes.â€

I don’t know many writers, in any genre, who can end a story on such a darkly poetic note without sounding maudlin.

28 February 2011 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.