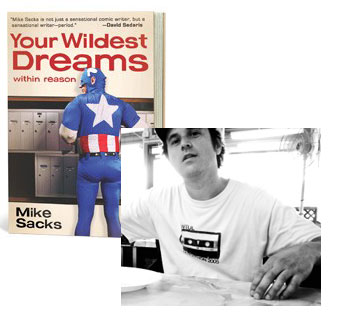

Mike Sacks and His Naked Admiration

There’s a copy of Mike Sacks’ Your Wildest Dreams, Within Reason somewere in this apartment, and if I could track it down I would quote for you verbatim from the piece within it that had me laughing out loud on the 7 train, especially since it was about the 7 train, at least glancingly. Oh, wait, that particular joke is online: “Kama Sutra: The Corrections.” (Note: Totally NSFW, which made reading it on a rush-hour subway train a bit of a challenge; eventually, I flipped back to “The Rejection of Anne Frank,” which Sacks co-wrote with Teddy Wayne; it’s actually probably even more outrageous, but at least not visually so.) And then there’s “IKEA Instructions,” which just flat out reduces both me and my wife to tears of laughter… Anyway, suffice to say Mike Sacks is my type of humor, and in this essay, Sacks pays tribute to one of his favorite humorists.

David Sedaris is always mentioned by both readers and writers as being one of their favorite humorists, and for good reason. Technically, I find him one of the best writers currently working, in humor or any other genre. All of his books are top-notch, but for the sake of this mini-essay, I’m going to mostly concentrate on his 1996 book Naked. And I’m going to talk about two things that impress me about his writing: his endings and his dialogue.

First, endings. Sedaris is a master at creating endings that end on just that perfect note of pathos and optimism (not an easy combination). This ending is from his story “Ashes,†a beautiful piece about the loss of his mother:

“Our mother was back in her room and very much alive, probably watching a detective program on television. Maybe that was her light in the window, her figure stepping out onto the patio to light a cigarette. We told ourselves she probably wanted to be left alone, that’s how stoned we were. We’d think of this later, each in our own separate way. I myself tend to dwell on the stupidity of pacing a cemetery while she sat, frightened and alone, staring at the tip of her cigarette and envisioning her self, clearly now, in ashes.â€

I don’t know many writers, in any genre, who can end a story on such a darkly poetic note without sounding maudlin.

Sedaris has been criticized for not adhering too strictly to historical fact, especially when it comes to dialogue, which I’ve always found ridiculous. Sedaris is a humorist first and foremost, and the most important job of any (worthy) humorist is to entertain. He’s not an historian. Often, historians aren’t even historians. How do we really know what was said five hundred, two hundred, even twenty-five years ago? And, besides, how entertaining would it be to really and truly be accurate? Stories would read as transcripts from C-SPAN, which, as anyone who has ever read a transcript from C-SPAN can tell you, is not the best way to pass the time on a beach or on a subway ride home from work.

Besides, Sedaris openly admits that he tweaks his dialogue to make it more entertaining! Creative writing teachers are constantly telling students to listen to the dialogue that exists around them and use what they hear when they write. While a worthy pursuit, try it sometime. It can be a bit, um, boring.

Some of my favorite pieces of Sedaris’s dialogues are up there with the best dialogue from any comedy film—going back to S.J. Perelman or even Woody Allen. This is from the story “Planet of the Apes,†and it takes place just after David is picked up while hitchhiking. The driver is a grizzled, elderly woman. David speaks first:

I told her my father was attending a peace conference in Stockholm, Germany, and that my mother was a long-haul truck driver on a run to the West Coast with a loadful of panty hose.

“Right,†the woman sad, tamping her cigarette into the smoldering ashtray, and I breast-feed baby camels in my backyard just for the freaking fun of it. Just tell me where you live, Pinocchio, and save me the baloney for lunch.â€

Or this, from the story “The Girl Next Door,†from his 2004 book Dress Your Family in Corduroy and Denim. Back story probably doesn’t even matter:

“Oh, he speaks Chinese now! Tell me, Charlie Chan, what’s the word for six straight hours of vomiting and diarrhea?â€

Or this, from “C.O.G.,†spoken by a middle-aged man named Curly; a charmer who lives in a trailer with his mother and collects artificial penises:

“So what do you think?†Curly said, lowering himself onto the waterbed.

“That’s really some . . . bedspread you’ve got there,†I said, hoping to focus the attention toward the color scheme. “It’s a real . . . orange orange, isn’t it?â€

“I guess you could say that,†he said, reaching over to stroke something that closely resembled a thermos. “What do you think of my toy collection? I figured you’d appreciate it more than anyone else I know. First time I saw you, I said to myself, ‘There’s a boy who needs a playmate.’ So what do you say, Charlie Brown, you ready to play?â€

What can I say? David Sedaris is the best. He’s at the top for a good reason. And I have very little doubt that he’ll stay there for a good long time.

28 February 2011 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.