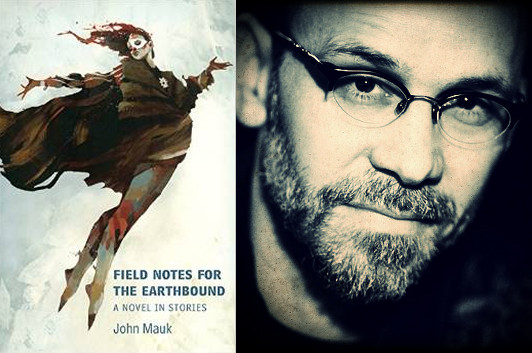

John Mauk: The Urgency of Lee K. Abbott

photo: JohnMauk.com

The stories in John Mauk‘s Field Notes for the Earthbound are situated into an uncanny niche between realism and fantasy—a world where magic is folded into the ebb and flow of everyday life… until it bursts through to the surface. But not everything that’s weird in John Mauk’s corner of Ohio is supernatural, and those parts of the stories have an unsettling power as well. In this essay, Mauk discusses another short story writer whose voice compels him with each reading…

If I get waylaid or traffic jammed, I want something to study, something dense and alluring. So I carry a book nearly everywhere I go. For several months, that book has been All Things, All at Once, a panoramic collection of new and selected stories by Lee K. Abbott. All Things has been shoved in my backpack and crammed in various bags. It has slithered between couch cushions and ridden along like a family dog in the backseat of my Honda. My past ride-alongs include Close Range (Annie Proulx), Seven Nights (Jorges Luis Borges), One Hundred Years of Solitude (Gabriel Garcia Marquez), Cloud Street (Tim Winton), The Postmodern Explained (Jean Lyotard), and Negotiations (Gilles Deleuze), books that reshape the neurological and emotional landscape, that are worthy of a million reads. Abbott’s collection is that worthy. It’s full of stories that go hard and characters that yearn like crazy.

When it comes to fiction, I want to be tossed around, lulled, and then awakened by a bucket of something, anything. I want the most lush experience possible. I want a narrator to undo my thinking, to pull my teeth out. I want to go all gummy into the next sentence or page. Don’t get me wrong: I don’t want hijinks. I’m not a fan of narrative trickery. What I’m after is a narrator that sizzles or shimmers in some weird way—a voice that walks up to the line of propriety, looks both ways, and then steps over it.

And here’s the thing about Abbott’s narrators: they feel urgent—as though they’ve been lost in the desert for months, as if they’ve just wandered into town with nothing but clarity. They sound wild-eyed and prophetic, rambling in some beautiful desert tongue. They have so much stuff to report, and it’s all crucial. Every speck, recollection, and fussy qualifier matters. Consider this passage from “Revolutionaries,” in which the narrator recalls how an old friend went politically rogue:

“Toward the end—before the campus cops and four state policemen broke it up by dragging Jimmy off—he delivered a rambling singsongy declaration that mentioned Abe Maslow, Aldous Huxley, Carol Rogers, D.T. Suzuki—names that passed over me like clouds. They were the dead or the living, or the never-were. I wanted him to talk—if that’s all this was—about being afraid, about what dead William Wordsworth’s verses skills had to do with anything, and about what I was supposed to be doing in five or ten years. But he went on—“We’re discussing human worth here!”—his hair flyaway, his T-shirt too small and covered with buttons, his cheeks painted like an Apache’s, ignoring the hecklers who said he was queer, or chickenshit, or a commie.”

29 November 2014 | selling shorts |

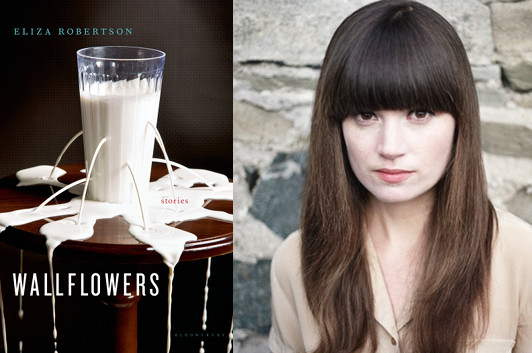

Eliza Robertson: A Voice Beyond Words

photo: via Bloomsbury

As I’m reading through Eliza Robertson’s debut collection, Wallflowers, the stories that stand out in my memory are often those where the characters find themselves grappling with profound emotional losses, like the young narrator of “Ship’s Log,” whose attempts to dig a hole to China from his grandparents’ yard in Ontario barely overly his grief and fear at his grandfather’s death, or the narrator of “My Sister Sang,” listening to the black boxes from crashed airplanes, or Natalie, the protagonist of “Where have you fallen, have you fallen?” whose story is told in reverse chronological order.

These stories, and others in the collection, show Robertson’s formal playfulness to strong effect. In this essay, she discusses how Jonathan Safran Foer pushes language even further—beyond the written word, even—to arrive at the right way of hitting his story’s emotional register.

My PhD subject is prose rhythm. I’ll spare readers the gory details, but rhythm has led me to think about voice—how we use that word so often we have forgotten it’s a metaphor. “Voice of a generation.” “New voice.” “A voice piece.” (Which often translates to: the characters talk funny.) From here, if you will follow me down the wormhole, I started to think about how the term “voice” is premised on utterance. Don’t get me wrong: I talk about voice in fiction too. I will continue to talk about voice. But I wanted another word that included silence, whitespace and punctuation. Enter rhythm. Enter also “A Primer for the Punctuation of Heart Disease” by Jonathan Safran Foer.

The title summarizes the story very well. It is a primer for the silences and emphases (read: punctuation) organic to the narrator’s family communication on love, the holocaust, and yes, heart disease. The sentiment emoted by these symbols is so much more urgent—even vital—than what could be relayed by words. That is: the symbols undercut, footnote and italicize what is spoken.

For example, in the following passage, the silence mark, â–¡, represents an absence of language, and â– , the “willed silence mark,” represents an intentional silence— often employed in response to questions you don’t want to answer. As seen here:

The “insistent question mark” denotes one family member’s refusal to yield to a willed silence, as in this conversation with my mother.

“Are you dating at all?”

“â–¡”

“But you’re seeing people, I’m sure. Right?”

“â–¡”

“I don’t get it. Are you ashamed of the girl? Are you ashamed of me?”

“â– ”

“??”

12 October 2014 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.