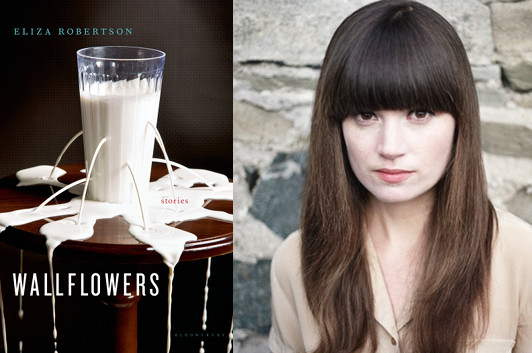

Eliza Robertson: A Voice Beyond Words

photo: via Bloomsbury

As I’m reading through Eliza Robertson’s debut collection, Wallflowers, the stories that stand out in my memory are often those where the characters find themselves grappling with profound emotional losses, like the young narrator of “Ship’s Log,” whose attempts to dig a hole to China from his grandparents’ yard in Ontario barely overly his grief and fear at his grandfather’s death, or the narrator of “My Sister Sang,” listening to the black boxes from crashed airplanes, or Natalie, the protagonist of “Where have you fallen, have you fallen?” whose story is told in reverse chronological order.

These stories, and others in the collection, show Robertson’s formal playfulness to strong effect. In this essay, she discusses how Jonathan Safran Foer pushes language even further—beyond the written word, even—to arrive at the right way of hitting his story’s emotional register.

My PhD subject is prose rhythm. I’ll spare readers the gory details, but rhythm has led me to think about voice—how we use that word so often we have forgotten it’s a metaphor. “Voice of a generation.” “New voice.” “A voice piece.” (Which often translates to: the characters talk funny.) From here, if you will follow me down the wormhole, I started to think about how the term “voice” is premised on utterance. Don’t get me wrong: I talk about voice in fiction too. I will continue to talk about voice. But I wanted another word that included silence, whitespace and punctuation. Enter rhythm. Enter also “A Primer for the Punctuation of Heart Disease” by Jonathan Safran Foer.

The title summarizes the story very well. It is a primer for the silences and emphases (read: punctuation) organic to the narrator’s family communication on love, the holocaust, and yes, heart disease. The sentiment emoted by these symbols is so much more urgent—even vital—than what could be relayed by words. That is: the symbols undercut, footnote and italicize what is spoken.

For example, in the following passage, the silence mark, â–¡, represents an absence of language, and â– , the “willed silence mark,” represents an intentional silence— often employed in response to questions you don’t want to answer. As seen here:

The “insistent question mark” denotes one family member’s refusal to yield to a willed silence, as in this conversation with my mother.

“Are you dating at all?”

“â–¡”

“But you’re seeing people, I’m sure. Right?”

“â–¡”

“I don’t get it. Are you ashamed of the girl? Are you ashamed of me?”

“â– ”

“??”

This story builds its own shorthand. The readers learn Foer’s symbols, and like acquiring a new language, you begin to listen for them and feel small bursts of gratification when you get it right. Foer plays with form in his other books too—particularly Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, which features erratically spaced letters from the protagonist’s grandparents. In this book, whitespace (and typographical spacing) convey as much emotion as the words themselves.

I disagree with the critics who find these experiments cheap. As in “A Primer for the Punctuation of Heart Disease”—silence mingles with words to represent the mystical unsaid in communication with loved ones. The succession of words and punctuation builds an anticipation of the beat—like a song you know, or a joke building to a punch line. And like a joke, this story is funny. It’s also wrenchingly sad. Jonathan Safran Foer masters that balance. Part of his facility with tragicomedy comes from, I think, his willingness to unhinge from normal language. Anyone who writes text messages with emoticons will understand the careful play needed to write without words. However, this story precedes the widespread use of emojis by at least five years. In fact, one of his punctuation marks, the “corroboration mark” is shaped like a smiley face:

It would be a mistake to think that it simply stands in place of ‘I agree,’ or even ‘Yes.’ Witness the subtle usage in this dialogue between my mother and father:

“Could you add orange juice to the grocery list, but remember to get the kind with reduced acid. Also some cottage cheese. And that bacon substitute stuff. And a few Yahrzeit candles.”

“☺”

“The car needs gas. I need tampons.”

“☺”

“Is Jonathan dating anyone? I’m not prying, but I’m very interested.”

“☺”In the above exchange, Foer makes decisions with “real” punctuation to sharpen the mother’s tone and persona—for example, the comma-but construction in the first sentence, followed by a series of fragments. Plus the parallel construction of: “The car needs gas. I need tampons.” These are decisions any writer must make, but they work in support of his kookier “corroboration marks”—which do shift in meaning, however subtle.

Puritans may suggest that a writer should only rely on careful word choice to convey tension, but why? There is an art to the text message. There is an art to emojis. (See: Emoji Dick.) It is the twenty-first century, and we have a larger tool box.

12 October 2014 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.