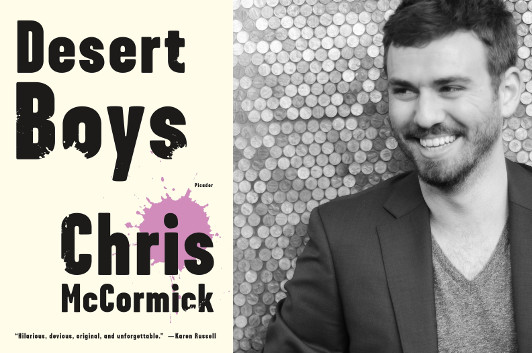

Chris McCormick & the Management of Grief

photo: Jenna Meacham

“The Antelope Valley is not the California most people imagine,” Chris McCormick writes. “This could be a good thing, but almost never is. The stories in McCormick’s debut collection, Desert Boys, are centered around Daley Kushner, a young man who grew up in Antelope Valley, left to go to school in Berkeley, and became a writer—much like McCormick himself. How much like, I wouldn’t know, but I can tell you that stories like “Mother, Godfather, Baby, Priest” and “You’re Always a Child When People Talk About Your Future” give a strong sense of what it must have been like to come of age as a gay, half-Armenian teenager in the desert north of Los Angeles in the years just after 9/11, and finding your way toward an adult identity as a twentysomething today.

I guess one reason for stories is the management of grief. The grief in question can be shared or private, but sometimes, fluttering between worlds, it can be both. Like a spirit, or—more interesting to me—like any regular person torn between an old home and a new home, or between belonging to a community and relying on an idea of selfhood, or between the raucousness of an inner life and the contrived but more palatable version we present to others. These conflicts, I think, are some of the prices we pay for freedom, and they only get more tangled and impossible to parse when grief, the fluttering kind, is involved.

Shaila Bhave, the narrator of Bharati Mukherjee’s “The Management of Grief,” has just lost her husband and sons to the terrorist bombing of Air India Flight 182. The plane—from Canada to Delhi through the UK—has exploded over Irish waters, killing the 329 people onboard, most of whom were Canadian-Indians visiting the country, and the family, they’d left behind.

Shaila—just one of hundreds in her community whose family has been ruptured by the attack—quickly garners a reputation as “a pillar,” somebody who has taken the tragedy “more calmly” than the others. But what others see as strength, Shaila understands to be a deep flaw: “This terrible calm will not go away.”

7 May 2016 | selling shorts |

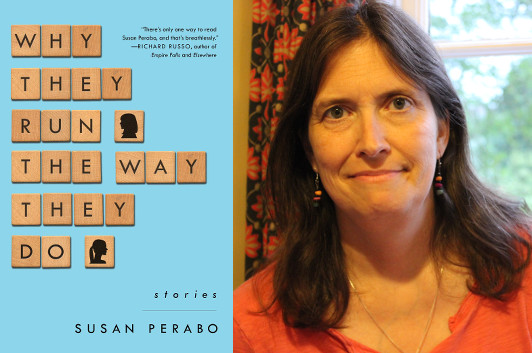

Susan Perabo & Wolff’s Audacious “Bullet”

photo: Sha’an Chilson

The short story Susan Perabo has chosen to write about is one of my own favorite short stories, and the thing that draws her to that story is similar to what draws me to “This Is Not That Story,” one of the stories in her new collection, Why They Run the Way They Do. Perabo plays with our recognition of the act of reading a short story, of the expectations that we bring to such an experience, of how it will be told and what it will tell us, and yet when she dodges and weaves past those expectations, the self-consciousness is barely visible, and never distracting. The metafictional elements are front and center, yet it’s the fictional components that have stayed with me long after I’ve finished reading. In her other stories, her technique calls even less attention to itself, but remains at that consistent level of excellence. If you care about short stories, Susan Perabo should be on your radar—if she hasn’t been before, then you’re in for a great surprise.

Great short stories happen to you. In this way, stories are more like poems than like novels. A short story is a singular, uninterrupted experience, an event, occurring all at once. If you are someone who is passionate about literature, you probably have at least one story that’s so profound an event in your life that you recall where you were when you first read it, in the same way you recall where you were when you received some important, life changing piece of news. In the case of the story, maybe your whole life didn’t change, but your reading life, or your writing life did.

One story that happened to me is Tobias Wolff’s “Bullet in the Brain.” I was at my job as a literature tutor for the intercollegiate athletes at the University of Arkansas. I was in the women’s study hall, located in the old Barnhill Arena. I was “on call,” which meant I sat around reading magazines until a student needed to talk with me about Oedipus or Gatsby or Marvell’s coy mistress. Most nights I was in the men’s study hall and worked pretty much nonstop, but once a week I was in the women’s study hall and had a lot of time to read. (Not a judgment—just an observation.)

The reading I had that night was the September 25th, 1995 issue of The New Yorker. It included the story “Bullet in the Brain,” which I noted happily was only three pages long. This was good because it meant I likely could read it without interruption.

7 March 2016 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.