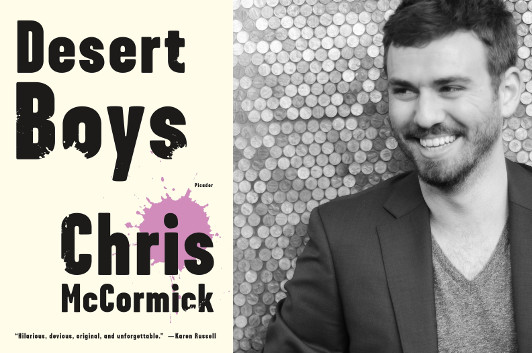

Chris McCormick & the Management of Grief

photo: Jenna Meacham

“The Antelope Valley is not the California most people imagine,” Chris McCormick writes. “This could be a good thing, but almost never is. The stories in McCormick’s debut collection, Desert Boys, are centered around Daley Kushner, a young man who grew up in Antelope Valley, left to go to school in Berkeley, and became a writer—much like McCormick himself. How much like, I wouldn’t know, but I can tell you that stories like “Mother, Godfather, Baby, Priest” and “You’re Always a Child When People Talk About Your Future” give a strong sense of what it must have been like to come of age as a gay, half-Armenian teenager in the desert north of Los Angeles in the years just after 9/11, and finding your way toward an adult identity as a twentysomething today.

I guess one reason for stories is the management of grief. The grief in question can be shared or private, but sometimes, fluttering between worlds, it can be both. Like a spirit, or—more interesting to me—like any regular person torn between an old home and a new home, or between belonging to a community and relying on an idea of selfhood, or between the raucousness of an inner life and the contrived but more palatable version we present to others. These conflicts, I think, are some of the prices we pay for freedom, and they only get more tangled and impossible to parse when grief, the fluttering kind, is involved.

Shaila Bhave, the narrator of Bharati Mukherjee’s “The Management of Grief,” has just lost her husband and sons to the terrorist bombing of Air India Flight 182. The plane—from Canada to Delhi through the UK—has exploded over Irish waters, killing the 329 people onboard, most of whom were Canadian-Indians visiting the country, and the family, they’d left behind.

Shaila—just one of hundreds in her community whose family has been ruptured by the attack—quickly garners a reputation as “a pillar,” somebody who has taken the tragedy “more calmly” than the others. But what others see as strength, Shaila understands to be a deep flaw: “This terrible calm will not go away.”

She tells the story in exactly that tone, a terrible calm borne of all the contradictory ingredients of grief: detachment and pain, helplessness and the need for control, utter confusion and the most dreadful clarity—so clear, at times, that it’s almost funny: “She learned this from a swami in Toronto. I have my Valium.” The result is yet another contradiction, deeply sympathetic and wholly unnerving. We get the frightening sense that the story is in the hands of a woman who might choose to stop telling it at any moment. That she might get up someplace in the middle and start walking in another direction, leaving the story like a package on a park bench for someone else to pick up and tell.

Maybe the story could be picked up by the rational Dr. Ranganathan, a widower and electrical engineer in whose “orderly mind, science brings understanding, it holds no terror.” Or maybe Shaila’s superstitious friend, Kusum, whose husband and favorite daughter are among the dead. Kusum has sold her house in Canada to live in an ashram in Hardwar, “pursuing inner peace.” Or maybe Judith Templeton, the well-intentioned but condescending white social worker assigned to the case, who seeks Shaila’s help in communicating with the more “hysterical” and unassimilated relatives of the victims.

Any of them would fail to talk about the management of grief without talking about the management of time, and Mukherjee’s brilliance is to understand that. Hazy months—years?—pass in these incredible seventeen pages, wherein Shaila and the other relatives of the victims travel from Canada to the Irish coast to India and back again. Eerily simple sentences (“Three months pass. Then another.”) unfurl in our minds: Why not “Four months pass”? Why the breakage? Why the present tense throughout the story, until the very end when another breakage occurs into the past tense? We sense we know the answers to these questions, and yet it’s so difficult to articulate them without sounding like frauds, like Judith Templetons, bureaucrats of grief. Here’s a story that confounds and moves us by saying perfectly what’s best left unsaid.

“I am trapped between two modes of knowledge,” Shaila tells us, halfway through the story, trapped there too. “At thirty-six, I am too old to start over and too young to give up. Like my husband’s spirit, I flutter between worlds.” Go read Bharati Mukherjee’s story. It does what all great stories do. It captures, however briefly, that fluttering.

7 May 2016 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.