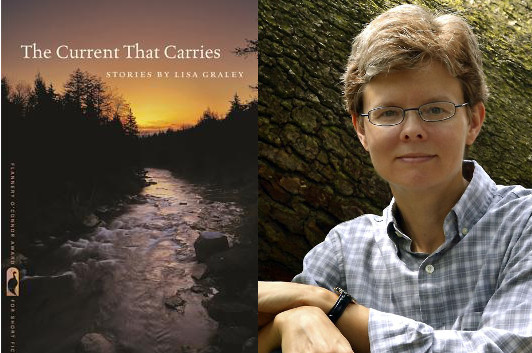

Lisa Graley: When Bad Things Happen to Good Characters

photo: Chelsea Ellison

Last year, the University of Georgia presented the Flannery O’Connor Prize to Lisa Graley for the short stories collected in The Current That Carries. One of the first things you’ll notice about Graley’s writing is her ability to get inside the heads of her characters, like the widower in “Vandalism” who starts out seeking payback against the joyriding teens who’ve been knocking over his mailbox but finds himself drawn into a much more complex emotional drama, or the narrator of “A Wild, to the Rim, Net or Nothing, Oven-Fired Ladling of Love,” reflecting on growing up in ’70s West Virginia, and how she and her grandmother formed an emotional bond watching Kentucky basketball star Kyle Macy. In many ways, Graley’s characters are defined by how to respond to crisis; in this essay, she reveals just how hard it is for her to put her characters in those situations…and how she’s learned to push through her resistance.

The first time I read Gabriel GarcÃa Márquez’s Love in the Time of Cholera and encountered Juvenal Urbino’s death, every thread of my readerly self cried, “Foul! You can’t kill the main character at the end of the first chapter!” I felt such attachment to the chess-playing, parrot-chasing, asparagas-urinating Doctor Urbino. I had invested so much. Hadn’t GarcÃa Márquez, as well?

It seemed as though Garcia Marquez had answered some kind of writer’s dare, loving and lingering over an adored character and then killing him so quickly. What audacity. What confidence.

Unlike Gárcia Márquez, I have a difficult time hurting my characters, much less killing them. Sure, I know pain is for their own good, and death, perhaps, good for some of their fellow characters. My hesitancy, I think, stems from a childhood where my brother and I played with toy guns but weren’t allowed to pretend-kill anyone. Aiming to maim was similarly discouraged.

Of course, characters aren’t people. But then again, they are. When you’re pulled into a story, you read to discover what happens to characters. You become involved—as if you were on an airplane hearing someone relate the true story of himself or herself or an acquaintance. When you’re writing, you tend to identify with characters the same way.

11 October 2016 | selling shorts |

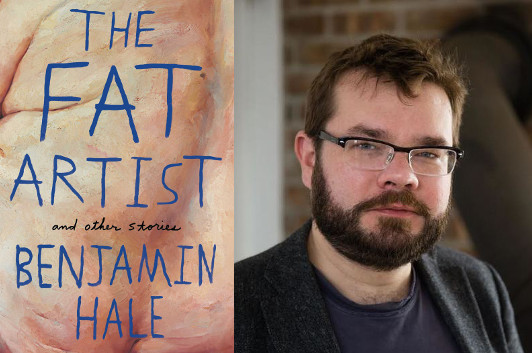

Benjamin Hale & “A Game of Clue”

photo: Pete Mauney

I liked Benjamin Hale‘s The Evolution of Bruno Littlemore, which I reviewed for Shelf Awareness, and I was eager to see what he’d do next. After all, a nigh-Nabakovian novel narrated by an intelligent chimpanzee is a hard act to follow—but The Fat Artist and Other Stories doesn’t disappoint. These stories are more naturalistic… well, okay, “The Fat Artist” exists in that twilight zone between absurdism and science fiction that Robert Sheckley used to detail so masterfully. But there are other great stories in here, like “If I Had Possession Over Judgment Day” or “Leftovers,” that take place in a world as real as real could be, even when events go to their most extreme. One of the things I particularly enjoy about this collection is that Hale gives his stories room to play out; it’s something he talks about in this guest post, in the context of one of his own favorite stories.

Steven Millhauser is one of two writers of whom I can say this: Whenever he publishes a new book, I drop whatever else I’m doing and immediately buy it and read it. (The other is Nicholson Baker.) I discovered Millhauser’s fiction in my early twenties, when someone recommended I read his first novel, Edwin Mullhouse: The Life and Death of an American Writer, 1943-1954, by Jeffery Cartwright. The local bookstore didn’t have it, but they did have The King in the Tree, a collection of three novellas that had just come out. I bought it, took it home, and within a few pages I was beginning to understand that I had opened the work of a writer who spoke directly and with rather uncanny precision to me, who clearly derived the same sort of pleasures from literature as I do.

In Millhauser, I found a very American writer who crafts Borgesian structures out of Nabokovian wit and wordplay, with as much humor and perhaps even more humanity than either Borges or Nabokov. Later, I did read Edwin Mullhouse (I hate hyperbole, but I consider that book to be one of a handful I can think of by living writers that I would call a “masterpiece”), and the rest of his published fiction, too.

Millhauser is a master of both long and short-form prose fiction, as well as a hybrid animal, the longish story/shortish novella. This might be my personal favorite form for prose fiction—both to read and to write. (The Fat Artist contains just seven stories, all of them on the long side, and a few of which are novella-length.) “The problem with stories,” I once heard Charles D’Ambrosio say, “is that they have to be efficient. Stories that aren’t efficient are novels.”

9 August 2016 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.