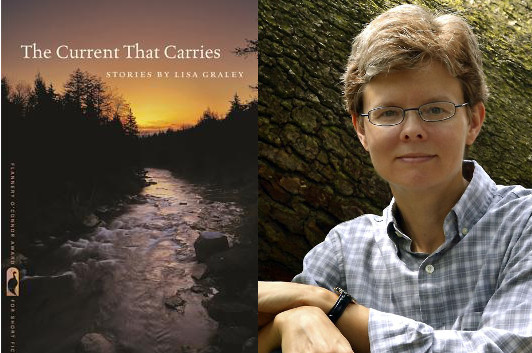

Lisa Graley: When Bad Things Happen to Good Characters

photo: Chelsea Ellison

Last year, the University of Georgia presented the Flannery O’Connor Prize to Lisa Graley for the short stories collected in The Current That Carries. One of the first things you’ll notice about Graley’s writing is her ability to get inside the heads of her characters, like the widower in “Vandalism” who starts out seeking payback against the joyriding teens who’ve been knocking over his mailbox but finds himself drawn into a much more complex emotional drama, or the narrator of “A Wild, to the Rim, Net or Nothing, Oven-Fired Ladling of Love,” reflecting on growing up in ’70s West Virginia, and how she and her grandmother formed an emotional bond watching Kentucky basketball star Kyle Macy. In many ways, Graley’s characters are defined by how to respond to crisis; in this essay, she reveals just how hard it is for her to put her characters in those situations…and how she’s learned to push through her resistance.

The first time I read Gabriel GarcÃa Márquez’s Love in the Time of Cholera and encountered Juvenal Urbino’s death, every thread of my readerly self cried, “Foul! You can’t kill the main character at the end of the first chapter!” I felt such attachment to the chess-playing, parrot-chasing, asparagas-urinating Doctor Urbino. I had invested so much. Hadn’t GarcÃa Márquez, as well?

It seemed as though Garcia Marquez had answered some kind of writer’s dare, loving and lingering over an adored character and then killing him so quickly. What audacity. What confidence.

Unlike Gárcia Márquez, I have a difficult time hurting my characters, much less killing them. Sure, I know pain is for their own good, and death, perhaps, good for some of their fellow characters. My hesitancy, I think, stems from a childhood where my brother and I played with toy guns but weren’t allowed to pretend-kill anyone. Aiming to maim was similarly discouraged.

Of course, characters aren’t people. But then again, they are. When you’re pulled into a story, you read to discover what happens to characters. You become involved—as if you were on an airplane hearing someone relate the true story of himself or herself or an acquaintance. When you’re writing, you tend to identify with characters the same way.

The written story may be imagined, but once a writer is conditioned not to pretend-kill, conjuring a hurricane, or disease, or accidental fall from a ladder is challenging. Usually, I perceive something bad is about to happen because it’s foreshadowed by something I’ve already written—like the aura some people report before a seizure. Still, it’s difficult for me to pull the trigger. Right now, for example, I’m in the early stages of a novel, having walked away for a year because I know what should happen, what everything has led up to, and yet can’t bring myself to draw blood.

Joseph Conrad claimed he liked to push characters as far as possible to see what stuff they were made of. Bad things often reveal character better than good things. In the Bible, Job loses everything and is left to pick up the shards. His relationships—with his wife, with friends, with God—are all strained and tested. In my story “The Sorrows You Can’t Enter,” I found myself exploring a similar loss—though it hurt me to maim my character. If you take away a man’s wife and child and cherished dogs, what pieces are left to pick up? Who can he turn to for help?

In another story, “Burial Ground,” I manage to pretend-kill an elderly farmer whose prized possession was his tractor. His death and his preparations for death allow his son to see him more clearly. This story, in some respects, follows the pattern set in Love in the Time of Cholera where Juvenal Urbino’s life is illuminated in flashback (a form of resuscitation?).

Continually, I have to remind myself that without disaster, we can’t know how the house is built. We don’t know what it can withstand. Did anyone remember to secure hurricane fasteners in the attic? Will the roof survive 120 mph winds?

Here in Louisiana, as I write this, we are digging out from historic flooding. The devastation is so widespread and pervasive that people who don’t normally volunteer are volunteering. The residents whose homes were inundated with water are tested every hour—with news from insurance companies about what isn’t covered, with the musty scents of wet carpet and sheetrock, and with weather reports predicting, of all things, more rain. Mired in mud-stink and a landscape strewn with soggy furniture, people have encountered despair, to be sure. Yet there are also reports of startling rescues in the front buckets of tractors, neighbors giving away free gyros, and unlikely friendships forged in the scurry to remove debris.

Of course, some storms do take down the house. Just as some blows are too severe to recover from—like the one Juvenal Urbino suffers when he falls while trying to catch a sassy parrot in the branches of his mango tree. But death does not have to be final, I keep reminding myself. It is, after all, pretend-death. And there is a consoling luxury in flashback.

11 October 2016 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.