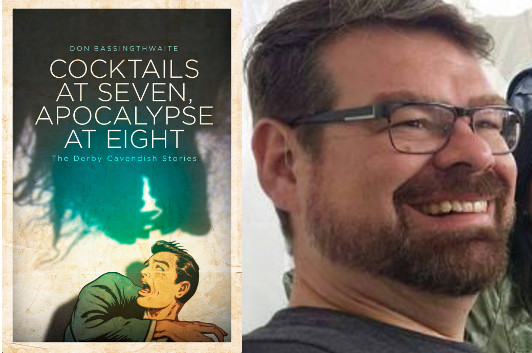

Don Bassingthwaite: Lovecraft Meets Maupin for the Holidays

photo courtesy ChiZine Publications

The stories in Don Bassingthwaite‘s Cocktails at Seven, Apocalypse at Eight are a hilariously campy addition to the tradition of supernatural stories for the holidays. It’s not just ghosts, although there is a ghost with a particularly Saturnalian thirst. Derby Cavendish, Bassingthwaite’s occult specialist, also comes across Krampus, a minotaur, a werewolf who’s also a drag queen, and a otherworldly spirit who manifests in the form of hideous Christmas sweaters. In this guest essay, Bassingthwaite explains how a Lovecraft pastiche that wasn’t quite working got boosted to a whole new level thanks to Tales of the City. Does that sound like a bit much? Well, as he says, “Stay with me on this because it works out.”

The very first incarnation of Derby Cavendish was in a story that I wrote nearly twenty years ago for submission to Strange Tales magazine. “Derby Cavendish and the Thing in the Cellar” was a gay pastiche of a Lovecraft story. It hit almost every Lovecraftian trope—Esoteric allusions! Eerie settings! Warped space-time! Squamous tentacles!—as it followed a dauntless and witty hero facing an Ancient Evil lurking in the basement of a gay bar.

I loved it. Strange Tales did not.

In hindsight, I can understand why. The Lovecraft influences were too strong, too blatant, too—in a word—sprawling. “The Thing in the Cellar” clocked in at almost 10,000 words. It was not a good story and, no, it’s not in Cocktails at Seven. But Derby was a good character. He was smart and confident. He didn’t let anything get in his way. He was magical in a world of secret magic and he was fearlessly flamboyant. He may have grown out of Lovecraft but he needed a better, more vibrant story—and story structure—than a Lovecraft pastiche could provide.

Which is where Armistead Maupin comes in.

If you’re not familiar with the Tales of the City books, they’re a slice of San Francisco life, written and set (at first) in the late 1970s and early ’80s. They’re full of wonderful characters both gay and straight interacting on a personal level and with larger events. They feel real, yet at the same time dramatic and thrilling. More importantly for my Derby Cavendish stories, Tales of the City started as a serial in the San Francisco Chronicle, each installment short and spare but captivating.

I adore Maupin’s magnificent stories and his amazing short form storytelling. His books are also the opposite of Lovecraft in almost every way: light and airy instead of dark and gothic, sparse instead of overblown, and focused on character rather than setting, with allusions that come across more like gossip than the arcana of lost ages. And, of course, they’re gloriously gay.

In 2010, when I was invited by the organizers of the Chiaroscuro Reading Series here in Toronto to read at their inaugural Very Special Christmas Special, I knew immediately that I wanted to revisit Derby Cavendish. The brief for the evening was to read something funny—and short. H.P. Lovecraft had already made a mark on Derby Cavendish, but as I wrote the my new story, I also kept Tales of the City in mind. Short. Fast-paced. Airy. Full of character. Gossipy. Gay I had covered.

The story from that first Christmas special was “Fruitcake,” the lead story in Cocktails at Seven, Apocalypse at Eight, and it was a hit. I’ve been reading a Derby Cavendish story at the Chiaroscuro Series holiday special every year since. I know they wouldn’t have been the same without the dual influence of H.P. Lovecraft and Armistead Maupin. I don’t imagine Lovecraft would be very impressed by them, but I like to think Maupin might.

24 December 2016 | selling shorts |

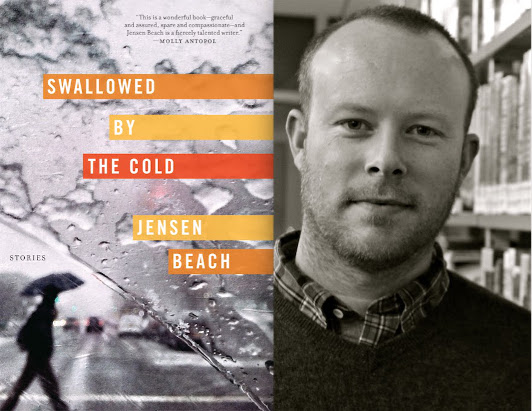

Jensen Beach & Jansson’s “White Lady”

photo: courtesy Jensen Beach

Bad things happen to good Swedish people over and over again in Jensen Beach’s second short story collection, Swallowed by the Cold. A man suffers a fatal accident riding his bike home along a canal; before he dies, he tries to get the attention of a passing sailboat, but the two couples on board simply wave back at him. The young girl who discovers his body will be haunted by the experience, and a neighbor tells her about the time he saw his first dead body. The owner of that sailboat? He’ll later die in a car crash, and the woman who finds him will find her life transformed as well… Of course, not every plight that befalls Beach’s characters is quite so stark, but even the smaller incidents are shot through with a dark emotional undercurrent, a sense that the protagonist’s lives could be upended at any moment, the defenses they’ve built up around themselves torn away. In his guest essay, Beach tells us about another brilliantly atmospheric story from a Scandinavian writer.

I first came to Tove Jansson through her children’s books about a family of troll-like creatures called the Moomins. These books and the television show they inspired are really popular in the Nordic countries. When my kids were small I spent a lot of time reading the books, watching the cartoon, and otherwise immersed in Moominland.

Jansson is best remembered for the Moomin books. But she also wrote five novels and six collections of short fiction. In 2014, NYRB Classics released The Woman Who Borrowed Memories, a marvelous selection of Jansson’s stories and a good place to start if you’re not familiar with her work. My favorite story in the collection, and one I teach so often that I’ve had to buy a second copy of the book because mine is so full of notes in the margins, is called “White Lady,” which first appeared in English in Jansson’s 1978 collection The Doll House.

“White Lady” is about fear and about desire. It’s about aging and, without being explicitly so, about death. Three middle-aged women travel to a small island in the Stockholm archipelago to dine at a restaurant. It’s late in the summer and the restaurant, soon to be closed for the season, is nearly empty. The three women, May, Regina, and Ellinor, arrive by boat, already a little drunk from having had “a drink or two before leaving home.” The restaurant is a “pale gray building […] very pretty in a melancholy way.” During dinner, the women all drink too much, bicker with one another over petty differences, share memories, and meet a group of young people who have come to the restaurant to dance. The evening winds to an end, and the women all leave the restaurant to go back to the dock to wait for the boat that will take them to the city.

12 December 2016 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.