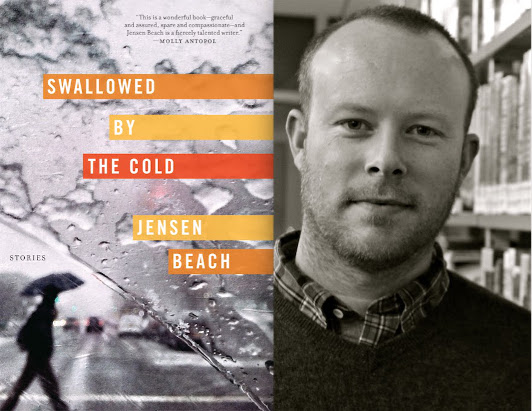

Jensen Beach & Jansson’s “White Lady”

photo: courtesy Jensen Beach

Bad things happen to good Swedish people over and over again in Jensen Beach’s second short story collection, Swallowed by the Cold. A man suffers a fatal accident riding his bike home along a canal; before he dies, he tries to get the attention of a passing sailboat, but the two couples on board simply wave back at him. The young girl who discovers his body will be haunted by the experience, and a neighbor tells her about the time he saw his first dead body. The owner of that sailboat? He’ll later die in a car crash, and the woman who finds him will find her life transformed as well… Of course, not every plight that befalls Beach’s characters is quite so stark, but even the smaller incidents are shot through with a dark emotional undercurrent, a sense that the protagonist’s lives could be upended at any moment, the defenses they’ve built up around themselves torn away. In his guest essay, Beach tells us about another brilliantly atmospheric story from a Scandinavian writer.

I first came to Tove Jansson through her children’s books about a family of troll-like creatures called the Moomins. These books and the television show they inspired are really popular in the Nordic countries. When my kids were small I spent a lot of time reading the books, watching the cartoon, and otherwise immersed in Moominland.

Jansson is best remembered for the Moomin books. But she also wrote five novels and six collections of short fiction. In 2014, NYRB Classics released The Woman Who Borrowed Memories, a marvelous selection of Jansson’s stories and a good place to start if you’re not familiar with her work. My favorite story in the collection, and one I teach so often that I’ve had to buy a second copy of the book because mine is so full of notes in the margins, is called “White Lady,” which first appeared in English in Jansson’s 1978 collection The Doll House.

“White Lady” is about fear and about desire. It’s about aging and, without being explicitly so, about death. Three middle-aged women travel to a small island in the Stockholm archipelago to dine at a restaurant. It’s late in the summer and the restaurant, soon to be closed for the season, is nearly empty. The three women, May, Regina, and Ellinor, arrive by boat, already a little drunk from having had “a drink or two before leaving home.” The restaurant is a “pale gray building […] very pretty in a melancholy way.” During dinner, the women all drink too much, bicker with one another over petty differences, share memories, and meet a group of young people who have come to the restaurant to dance. The evening winds to an end, and the women all leave the restaurant to go back to the dock to wait for the boat that will take them to the city.

The three women share a certain set of fears and desires. That is, they are, in their individual ways, afraid of growing old. They long for the past, for sexual vibrancy, for adventure, for beauty, for health, for professional successes long since lost to the years. Regina continuously reminisces about a trip to Venice she once took; May’s obsession with health speaks to her own fears distinctly; and Ellinor, who is a writer, appears to have run out of ideas and surrendered to her frustrations. The entirety of the story—its events, characters, sensual details—all arrange around this complicated but totally recognizable emotional center.

Partly, Jansson accomplishes this with the story’s atmosphere. Fog creeps across the veranda and later into the restaurant itself. Whether it’s this or the fog of alcohol or of memory or the tulle curtains in the ladies’ room, there is, throughout the story, a veil cast over each of its objects and all of its emotional depths, a barrier that is at times thin and translucent, but always there.

This same veil can be found in the way Jansson renders action. Apart from a handful of instances of indirect reported speech, very little of the story is settled in exposition. There are moments—I quoted two of them above, of course, but they are rare. Even gesture and movement are rendered in dialogue. Take the following:

“You know one time in Venice I drank a White Lady, or rather actually it was outside Venice at that casino, whatever it’s called. That was my first White Lady. Cheers, girls! Anyway, there I was and I was so young they wouldn’t let me in without an escort. Well, along came this bank director from Fiume—”

This is such a lively passage. There’s not a single moment of expository direction here. And yet in the parentheticals, the self-correction, the double adverb of “rather actually,” the “Cheers, girls!” so much action and movement is obviously present. Regina, in her monologue, becomes a part of the setting. She becomes a feature of the narrative much like the fog creeping in from the veranda, the too-loud music that the young people are listening too, the grin on the waiter’s face. Her movements, though they are only implied, become a part of the story’s visual palette. It’s an effective move because it achieves that neat trick of good fiction. It makes the messy stuff at the center of the story—the fears and desires and pains of the characters—at once startling clear and undefined.

Jansson, who trained as a painter, renders the story with a visual fluency that is remarkable precisely because it is present without being present. It is obscured, and the pleasure of the story, perhaps all stories, is found in being invited to look through this veil and try our hardest to make a coherent shape out of what we see.

12 December 2016 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.