Nick Lantz, “Battle of Alexander at Issus”

Off in the mountains a hermit checks

his rabbit traps before returning

to his hut for the night. The rabbits grow

bold near dawn and dusk, the hours

when clouds lower ladders of light

down the mountainsides. The hermit

hasn’t admired this light in decades.

At this time of day he is always bent

low, unfastening the thin leather snares

from around still-warm necks. If he hears

what sounds like thunder in the valley

one cloudless evening as he ties another

limp body to his belt, he thinks only

of returning home to bed, the rabbit fleas

that torment his sleep, the door that never

quite closes against the cold night air.

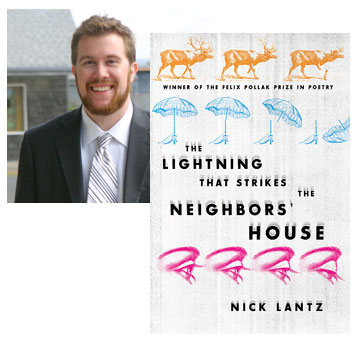

Back in February, I featured another Nick Lantz poem, “Lacuna, Triptych of the Battle,” from the collection We Don’t Know We Don’t Know. The poem above is from the second of Lantz’s collections published this year, The Lightning That Strikes the Neighbors’ House, which also contains “Portmanterrorism” (from The Writer’s Almanac). Oh, and back when I wrote about We Don’t Know…, I didn’t know you could find “Your Family’s Farm, Empty” online, or maybe you couldn’t, then.

Lantz discussed this book in an interview with The Rumpus: “It’s the much-revised remnants of my MFA thesis, and it had been collecting rejection slips since 2005. A poem in that book alludes to the Ship of Theseus, a boat that was supposedly maintained over many years by replacing its parts piecemeal as they deteriorated, begging the question of whether it was still the same ship, and, if not, at what point it ceased being that original ship. That’s how I feel about The Lightning. If you were to dig up my actual MFA thesis (please don’t), you’d see only a handful of the original poems. With The Lightning, I worked from the poems up. I was figuring out what that book was about as I assembled, disassembled, and reassembled it.”

By the way, Rumpus readers were also treated to the premiere publication of another Lantz poem: “How to Dance When You Do Not Know How to Dance.”

7 July 2010 | poetry |

Stephen Dunn, “In the Open Field”

That man in the field staring at the sky

without the excuse of a dog

or rifle—there must be a reason

why I’ve put him there.

Only moments ago, he didn’t exist.

He might be claiming this field

as his own, centering himself in it

until confident he belongs. Or

he could be dangerous, one of those

men who doesn’t know

why he talks to God.

I thought of making him a flamingo

standing alone on one pink leg,

a symbol of discordancy

between object and environment.

But I’ve grown so weary of inventions

that startle but don’t satisfy.

I think he must have come to grieve

a good friend’s death, and just wants

to stand there, numbly, quite sure

the sky he’s looking at is vacant.

But I see that he may be smiling—

his friend’s death was years ago—

and he might be out there to savor

the solitary elation of having discovered

what had eluded him until now.

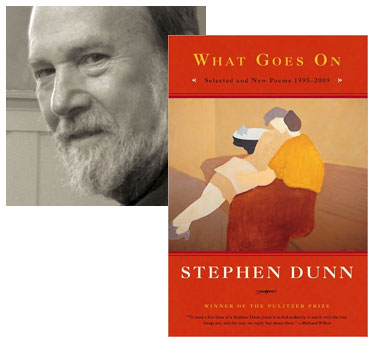

Two years ago, I featured “Madrugada” from Stephen Dunn‘s Everything Else in the World and mentioned that The New Yorker had published a new poem, “History,” that was not in that collection. You’ll find it in What Goes On: Selected and New Poems 1995-2009, along with “Talk to God” (the Poets Out Loud website), “And So” (How a Poem Happens, with commentary from Dunn on the creative process!), and “Zero Hour” (from the collection Different Hours, republished on Beliefnet).

It does not include “If a Clown” (also published in The New Yorker), which is a shame, because that’s a great poem. And maybe it’s a great illustration of a point Dunn made in an interview with Guernica back in 2004: “It seems to me that no matter how perverse or private you might think your attitudes are about anything, if you speak them well there’ll always be a few others nodding,” he said. “My best experiences with literature as a reader have been when something that I thought was freaky about myself, or something odd or private that I hadn’t told anybody, got articulated or enacted in a poem or story or a novel. It simply brings us into the human fold. Literature at its best is communal in that way.”

30 June 2010 | poetry |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.