Linn Ullmann’s Blessed Child Reborn, in English

Linn Ullmann found the beginnings of her latest novel, A Blessed Child, in the image of a boy running through a landscape similar to that of Fårö, a small island off the coast of Sweden where she spent summers as a child. “Why is this boy running?” she asked herself, and then she linked that image to a popular theme from Norwegian folklore, stories about a king and his three daughters… Exploring the relationships between those two images, she says over tea, led her to the story.

Ullmann was born in Oslo, the daughter of Liv Ullmann and Ingmar Bergman, but she came to the United States as a teenager and stayed for college at NYU (“I’m still missing that essay on Conrad that was going to get me my master’s degree”), so her English is flawless, which led me to ask how active a role she plays in the translation of her novels from Norwegian. She works very closely with Sarah Death, “one of the best translators in Scandinavian literature,” emailing back and forth repeatedly to cover every aspect of the book, from the folksongs to the teenage slang of the 1970s, and to resolve distinctions between British and American English. Then, once an English manuscript had been presented to Knopf, Ullmann went over it again with her editor; “it was almost like writing the book all over again,” she says of the process.

Because her parents were often working on location, Ullmann spent a lot of time as a child with her maternal grandmother, who was a bookseller, and this fueled the young girl’s “ferocious appetite for reading.” Before pursuing her literary aspirations, however, Ullmann wanted to be a dancer, an ambition her father fully encouraged, building her a practice studio on Fårö. She became serious about writing while in college, and during her twenties was a literary critic for the Norwegian press. I ask her if the “crisis in book reviewing” has hit Scandinavia: “There’s still a lot of room for book reviews and articles—even in the tabloids,” she tells me. And, in “one of the wonderful sides of social democracy,” the National Library will order roughly 1,000 copies of any book published in Norway, to make sure Norwegians from one end of the country to the other have access to the same books. That frees publishers to select books for literary quality without purely commercial motivation, she says, “and publishers have the time to build an author… It’s generated a lot of good literature.”

Who’s a Norwegian writer Americans probably haven’t heard of yet but should know? Ullmann recommends Dag Solstad, who has had one book translated into English so far: Shyness and Dignity.

6 October 2008 | interviews |

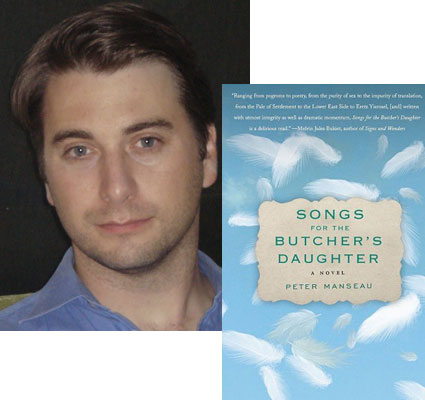

Peter Manseau: It’s Okay to Think This Book Is About Me

“Whenever I’ve attempted fiction, it’s never had anything to do with my life,” says Peter Manseau—but that doesn’t mean he won’t play with the old stereotype of the autobiographical first novel. Like Manseau, the unnamed young co-protagonist of Songs for the Butcher’s Daughter uses the Hebrew he learned in college to organize collections of Yiddish literature at a book depository, and “I don’t mind the association,” he tells me; if readers think he’s that character, he theorizes, it may lend additional plausibility to the story about meeting an aging Yiddish poet, Itsik Malpesh, and translating the memoirs of his childhood in Kishinev and emigration to New York. (It’s a testament to his skill as a writer, by the way, that you can read the entire story and never realize that the character’s name never comes up; he still feels so real in a psychological and emotional sense that it doesn’t matter.)

“Originally I thought the novel was going to be entirely Malpesh’s memoirs,” he explains as we chat at the counter of a Union Station coffee shop near his Washington, D.C. home. “But I felt that there was a point of access for the reader that was missing… It felt like historical fiction of the sort that I enjoy reading but did not want to write.” By adding the perspective of the young translator, Manseau hopes that readers have “a place to stand in relation to Malpesh,” especially when it comes to the revelations about his past in the novel’s later chapters—revelations which radically disrupt Malpesh’s self-presentation.

19 September 2008 | interviews |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.