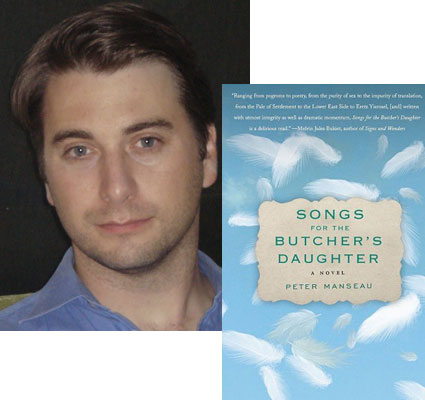

Peter Manseau: It’s Okay to Think This Book Is About Me

“Whenever I’ve attempted fiction, it’s never had anything to do with my life,” says Peter Manseau—but that doesn’t mean he won’t play with the old stereotype of the autobiographical first novel. Like Manseau, the unnamed young co-protagonist of Songs for the Butcher’s Daughter uses the Hebrew he learned in college to organize collections of Yiddish literature at a book depository, and “I don’t mind the association,” he tells me; if readers think he’s that character, he theorizes, it may lend additional plausibility to the story about meeting an aging Yiddish poet, Itsik Malpesh, and translating the memoirs of his childhood in Kishinev and emigration to New York. (It’s a testament to his skill as a writer, by the way, that you can read the entire story and never realize that the character’s name never comes up; he still feels so real in a psychological and emotional sense that it doesn’t matter.)

“Originally I thought the novel was going to be entirely Malpesh’s memoirs,” he explains as we chat at the counter of a Union Station coffee shop near his Washington, D.C. home. “But I felt that there was a point of access for the reader that was missing… It felt like historical fiction of the sort that I enjoy reading but did not want to write.” By adding the perspective of the young translator, Manseau hopes that readers have “a place to stand in relation to Malpesh,” especially when it comes to the revelations about his past in the novel’s later chapters—revelations which radically disrupt Malpesh’s self-presentation.

So if Songs isn’t about Manseau’s life, what is it about? He describes it as a way of explaining to himself why he became so fascinated with Yiddish literature, connecting the stories of those Jewish immigrants to America with his own experience as the son of a former Roman Catholic priest and nun who had tried to walk away from his religious background. “I identified with these guys,” he says. “I felt we had some similar life experiences… they were trying to leave behind their traditions, but found as they wrote that they couldn’t get away.”

At the Yiddish Book Center (“a very vibrant place devoted to this thing that was dying”), he learned to read the language, and frequently came across self-published memoirs by people who considered themselves serious writers… who nevertheless had chosen to tell their stories in “a language they knew their children would never read.” (It was here, too, that he came across the Yiddish translations of the New Testament, one of which plays a central role in Songs.) But though he went on to do some freelance work as a typesetter for new Yiddish-language books after leaving the Center, these days Manseau admits his Yiddish is “not so good.”

19 September 2008 | interviews |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.