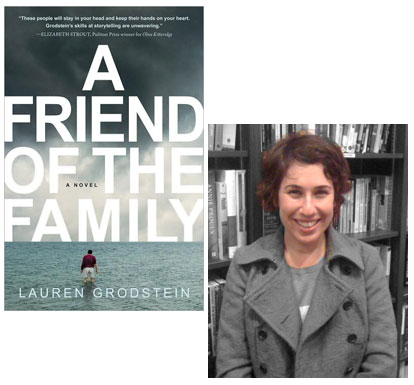

The Voice That Freed Lauren Grodstein from a Narrative Dead End

Starting in 2004, Lauren Grodstein recalled, “I spent three years writing a book that went nowhere. The bigger it got, the worse it got.” After a six-month period of “questioning everything,” she woke up one morning with a new character’s voice in her head. “I knew he had done something wrong,” she explained to me, “but I didn’t know what.” So she wrote what she heard all morning, took herself out to lunch, then came back, looked at the pages, and liked what she saw. Three and a half months later, Grodstein had a first draft of A Friend of the Family, in which Pete Dizinoff reveals to readers (in his own meandering way) just how his life went wrong: “It was like he was sitting on my shoulder, dictating.”

Grodstein was inspired in part by real-life incidents she’d read about in the 1990s, when teenage girls would give birth in public rest rooms or similarly inappropriate places then kill the infants or leave them to die (or be discovered). “Those stories had always haunted me,” she said, and soon she found herself exploring how a girl who would do something like that would intersect with a doctor in his mid-fifties like Pete. (It’s not giving too much away to say that it’s ten years after the incident, and the girl in question, the daughter of Pete’s best friend, is embarking on a relationship with Pete’s college-age son, and Pete’s not happy about that.) The story unfolds after everything has gone to hell, freeing Grodstein to write about the consequences of Pete’s actions while he’s recounting the events, reaching back and jumping forward in his chronology over and over. The non-linear narrative line has drawn some complaints, but “it was never a conscious decision that I would put this digression here, this explanation here,” she insisted, describing the way she wrote it as “just as if I was telling you a story.”

The other complaint some early readers and reviewers have had is that Pete’s an unlikable character—a complaint neither Grodstein or I really quite got, as the point of the novel isn’t that you’re supposed to like Pete, but you’re supposed to recognize the humanity of what he did. Sure, he’s willing to sabotage his son’s romantic relationship, but he’s doing it to protect what he considers to be his son’s best interests, and for that he won’t apologize. “Pete’s a lot more honest than some people,” Grodstein conceded. “Maybe honesty makes you unlikable.” Overall, though, she’s having a great time promoting the novel, her first for Algonquin Books, and observes that “it’s a sad book, but it’s brought me a lot of joy.” Not only did it break her out of that three-year dead end, you see, but her agent was able to sell it, fifteen months ago, the day after the birth of her son.

1 December 2009 | interviews |

Lauren McLaughlin Cycles Back to Jack & Jill

Late last week, I went out to Brooklyn to chat with Lauren McLaughlin about her two YA novels, Cycler and (Re)Cycler, which are about a teenage girl, Jill McTeague, who instead of getting a period transforms for several days every month into a boy, who has established a separate identity for himself as “Jack” despite (or maybe beacuse of) the efforts of Jill and her parents to keep him contained. I started out by asking McLaughlin about the ways in which, after essentially behaving as pure unreconstructed id in the first novel, Jack begins to develop a more nuanced personality in (Re)Cycler…

It’s fairly easy to interpret the two novels as an extended allegory about teens struggling with queer identity in general and trans identity in particular, but McLaughlin observes that many other teen readers could identify with Jill’s turmoil in the first novel, as she’s fundamentally “a girl who is desperately trying to hide a secret” about herself that causes her shame and, like any adolescent, “[she’s] not complete yet. She’s still in the process of inventing herself.” She admits, though, that Jack was her favorite character to write; with Cycler especially, “Jill, as the main point of view character, was harder for me to know. It took several drafts before I felt like I understood her.”

Could that mean, I suggested, that if she were to return to the characters, later novels could bring Jack even further into the foreground than (Re)Cycler? It’s a tricky question, she said, and not just because it would mean tampering with the biological link to Jill’s monthly cycle that defines their relationship. She’s given the various possibilities a lot of thought, and it’s an almost “existential” problem: “If I were to combine them into one character,” she offered, pondering one option, “does that mean that one of them is no longer part of the story? Or could they become somebody else entirely?”

I also wondered if McLaughlin was a Ranma 1/2 fan, but she swears she’s never seen it. “People have been asking me about it more and more, though,” she said. “I really need to catch up with it at some point.”

(By the way, this was the penultimate stop on a week-long blog tour for McLaughlin; if you want to read more, be sure to check out some of her other appearances.)

23 November 2009 | interviews |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.