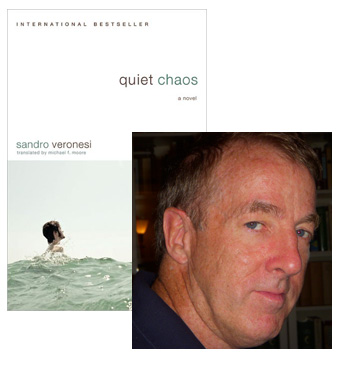

Michael F. Moore & the Voice of Quiet Chaos

Michael F. Moore describes Sandro Veronesi’s Quiet Chaos, which he translated from the Italian, as “driven not so much by plot or character as by a dynamic narrative voice,” and you’ll see what he means soon after you plunge into the opening chapters—much like Pietro Paladini, the novel’s narrator, dives into the ocean to save a random stranger, little knowing the tragedy that awaits him when he comes back home. Pietro’s conversational tone as he describes his slow, awkward adjustment to his life’s new circumstances is key to the novel’s success, and though I don’t have the Italian to compare it to the original, I’m hooked by the voice that Moore coaxed into English prose. In addition to Quiet Chaos, Moore (the chair of the PEN Translation Fund) has also translated The Day Before Happiness, by Erri De Luca, and Pushing Past the Night, by Mario Calabresi. He’s currently working on a new translation of a 19th-century classic, Alessandro Manzoni’s The Betrothed.

I’ve always hated folk sayings, with their easy dismissal of life’s many complexities. My least favorite is one I first heard tossed in my direction: “Guests are like fish; after three days they stink.” In my experience the opposite is true. Fish smells for the first three days, after which you either get used to it or the odor simply goes away. Like most New Yorkers, I don’t always have the patience (which we call “time”) to explain to visitors the ins and outs of my apartment and the city, and I dislike having to tiptoe past slumbering guests in the living room while on my way to work. Worse still are the early birds who interrupt my breakfast regimen of absolute silence and attempt, heaven help them, to start a conversation. But, after three days, this sense that my sacred space has been violated seems to dissipate, as the guests become adept at my rituals and I at theirs. Unfortunately most of them leave before we reach that point.

Translating a book can be like having a house guest who never leaves. I thought of this often when I was translating Quiet Chaos by Sandro Veronesi. A longer read, at 417 pages, than most of the previous works I had translated, it—or rather he—took up residence in my apartment for a good six months and came back for shorter stays of two to three weeks during the revision process. I kept him in the dining room and there he was, waiting for me every morning when I got up, eager to speak. All I really had to do was rub the sleep out of my eyes and, coffee mug in hand, sit down and prepare for a good listen. He was a delightful houseguest, and I fussed over him every day to make sure he had the right look, the right sound, and especially the right verve.

Quiet Chaos, in the grand tradition of Italian narrative (literature and film), is not so much about things happening as it is about stopping time in its tracks and nailing it to one place. After a momentous opening chapter when the narrator rescues a drowning woman only to learn when he gets home that his companion has suddenly died, the plot grinds to a halt. While other people’s words—of condolence, of comfort, even of confession—swirl around him, Pietro seeks a point of stillness. His inward turn is reflected in the language, consisting of long uninterrupted stream of consciousness passages, punctuated by abrupt intrusions from the outside world. He keeps waiting for grief to strike, unaware that he is living his life in its grip.

4 July 2011 | in translation |

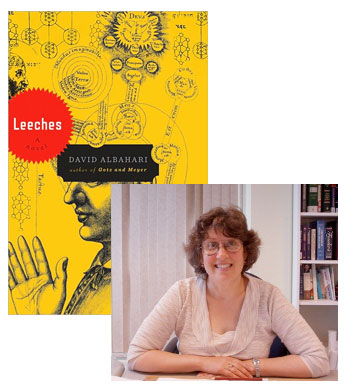

Ellen Elias-Bursac & Albahari’s Amusing Leeches

Ellen Elias-Bursaċ has plenty of experience translating the Serbian author David Albahari—her English-language version of his novel Götz and Meyer won the ALTA Translation Award and was tapped for the Barnes & Noble Discover promotion, which is no mean feat for a translated novel, let me assure you. So when a former colleague sent me a copy of Albahari’s latest, Leeches, I thought it would be interesting to hear from Elias-Bursaċ about what attracts her to Albahari’s stories.

Leeches is a thriller, narrated from an undisclosed location outside of Serbia, reprising events that transpired in the spring of 1998 in wartime Belgrade and building to the months just before the NATO bombing campaign. The narrator’s position of exile links it to much of Albahari’s writing during the 1990s, when he was situating his protagonists in Canada (Bait, Snow Man, Globetrotter) and dealing with the war at a continental remove, but, in contrast, the story the narrator tells us in Leeches is situated directly in Belgrade, smack in the middle of the war.

The suspense generated by the thriller format works well to convey the atmosphere of suspended animation in the year before the NATO bombing. Suspended animation is, perhaps, the best way to describe the bated-breath atmosphere the novel creates. In fact the protagonist (never named) and his best friend, Marko, get stoned at frequent intervals throughout the novel. It’s not only their spacy highs and disjointed conversations, but the actual holding of breath in the process of getting high, that typifies for me the feel of the novel. This sense is further enhanced by the format of a single paragraph for the whole novel.

Spacy highs notwithstanding, the novel does not sidestep the reality it addresses. Unlike Götz and Meyer, which refracts questions of wartime responsibility through World War II, Leeches takes on the Miloševiċ regime and the culture it spawned front and center. His protagonist is a Serbian writer who finds himself embroiled in a mysterious, sometimes mystical, chase after an elusive beautiful woman, Margareta, and a mysterious, regenerating manuscript tied in various ways to the Jewish communities of Belgrade and Zemun (a city just across the Danube from Belgrade), and, perhaps, to the protagonist himself. Not so elusive are the neo-Nazi repercussions to his involvement with Jewish themes: attacks on his person, his apartment, the newspaper he works for, that ensue after he begins writing in his regular newspaper column about the plight of Serbian Jews.

The context of the tense, grim story line makes the fact of the humor of Albahari’s writing all the more striking. It’s the humor that motivates me, as a translator, to translate David Albahari’s writing. His protagonists are often rather solemn, first-person characters, usually urban intellectuals, seldom named. While never bumblers, Albahari’s protagonists are often bewildered by what happens to them and their innocence of the obvious brings a dark laughter to the bleakest of situations.

29 April 2011 | in translation |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.