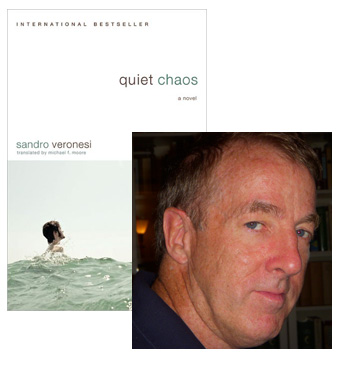

Michael F. Moore & the Voice of Quiet Chaos

Michael F. Moore describes Sandro Veronesi’s Quiet Chaos, which he translated from the Italian, as “driven not so much by plot or character as by a dynamic narrative voice,” and you’ll see what he means soon after you plunge into the opening chapters—much like Pietro Paladini, the novel’s narrator, dives into the ocean to save a random stranger, little knowing the tragedy that awaits him when he comes back home. Pietro’s conversational tone as he describes his slow, awkward adjustment to his life’s new circumstances is key to the novel’s success, and though I don’t have the Italian to compare it to the original, I’m hooked by the voice that Moore coaxed into English prose. In addition to Quiet Chaos, Moore (the chair of the PEN Translation Fund) has also translated The Day Before Happiness, by Erri De Luca, and Pushing Past the Night, by Mario Calabresi. He’s currently working on a new translation of a 19th-century classic, Alessandro Manzoni’s The Betrothed.

I’ve always hated folk sayings, with their easy dismissal of life’s many complexities. My least favorite is one I first heard tossed in my direction: “Guests are like fish; after three days they stink.” In my experience the opposite is true. Fish smells for the first three days, after which you either get used to it or the odor simply goes away. Like most New Yorkers, I don’t always have the patience (which we call “time”) to explain to visitors the ins and outs of my apartment and the city, and I dislike having to tiptoe past slumbering guests in the living room while on my way to work. Worse still are the early birds who interrupt my breakfast regimen of absolute silence and attempt, heaven help them, to start a conversation. But, after three days, this sense that my sacred space has been violated seems to dissipate, as the guests become adept at my rituals and I at theirs. Unfortunately most of them leave before we reach that point.

Translating a book can be like having a house guest who never leaves. I thought of this often when I was translating Quiet Chaos by Sandro Veronesi. A longer read, at 417 pages, than most of the previous works I had translated, it—or rather he—took up residence in my apartment for a good six months and came back for shorter stays of two to three weeks during the revision process. I kept him in the dining room and there he was, waiting for me every morning when I got up, eager to speak. All I really had to do was rub the sleep out of my eyes and, coffee mug in hand, sit down and prepare for a good listen. He was a delightful houseguest, and I fussed over him every day to make sure he had the right look, the right sound, and especially the right verve.

Quiet Chaos, in the grand tradition of Italian narrative (literature and film), is not so much about things happening as it is about stopping time in its tracks and nailing it to one place. After a momentous opening chapter when the narrator rescues a drowning woman only to learn when he gets home that his companion has suddenly died, the plot grinds to a halt. While other people’s words—of condolence, of comfort, even of confession—swirl around him, Pietro seeks a point of stillness. His inward turn is reflected in the language, consisting of long uninterrupted stream of consciousness passages, punctuated by abrupt intrusions from the outside world. He keeps waiting for grief to strike, unaware that he is living his life in its grip.

The novel is therefore driven not so much by plot or character as by a dynamic narrative voice, barreling down a single road from the first page to the last, veering from elation to despondence, dreamy escapism to gritty reality, ironic observation to wistful apology. My challenge was to capture every nuance and bend on that road. I had to create a work in colloquial American English that took flight from the Italian rather than being earth-bound by it. And since the text consists of a single monologue, every word had to sound completely natural.

In addition to being a very cerebral process, translation is highly emotional. We sit down to work with a certain trepidation, struggle through some passages, dash through others, laugh out loud and sometimes groan in frustration. There is always a risk that our own emotions, in art as in life, will cloud our perceptions and color our expressions, overwhelming the original author. But there is no shirking the emotional task of translation. Luckily the line between being over- and under-wrought is not so fine. I did my best—consciously and not—to identify deeply with the emotions in the text, make them mine, and write them out.

There were more than a few dead ends, I have to confess, but the most liberating and energizing moment came when I found out that Veronesi himself had done a translation, and of a truly protean text: Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, by Hunter S. Thompson. And he was a huge fan of David Foster Wallace, going so far as to create a small publishing house just so that Infinite Jest might be translated and published in Italy. With that tidbit of knowledge I put my own fear and loathing behind, buckled my seat belt, and put my pedal to the metal (the keyboard is still smoking).

4 July 2011 | in translation |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.