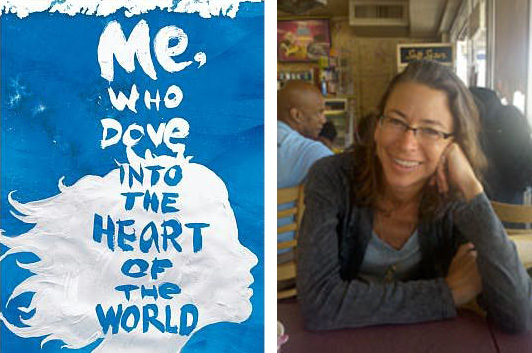

Lisa Dillman: Finding Me‘s Voice

photo via Words Without Borders

Translating a first-person narrator into English from another language can be a challenge under any circumstances, but when that narrator has a non-standard emotional and mental profile like Karen, the autistic protagonist of Sabina Berman’s Me, Who Dove into the Heart of the World, the work gets harder. Lisa Dillman rises to the occasion, though—and, in this guest essay, reminds us that when we think, before we even open a novel, that we know what it and its characters are going to be about, that’s when we’re most likely to be caught off guard by the author’s real plans.

When I first read Me, Who Dove Into The Heart of The World, I became obsessed with the idea of translating it, and a year later I was thrilled to get the opportunity to do so. The novel tells the story of Karen, a highly-functioning-autistic-cum-bluefin-tuna-industry-magnate. She starts the novel as a mute, feral, wild-child eating wet sand in Mazatlán, Mexico and ends up in a Tokyo penthouse surrounded by multiple laptops. In case it’s not immediately apparent, this is a highly unusual novel. And one I fell in love with for multiple reasons.

To begin with, there is Karen’s unique voice. She speaks—and writes—in clipped sentences devoid of “standard human” frippery. Karen is a literalist. When out on a fishing boat with an Italian sailor who claims God gave humans license to kill, she wants to see the license. She lacks inflection and eschews metaphor, euphemism and fantasy, all of which she classifies as lies used by “standard humans” in the name of deceit and self-delusion. Euphemism, for instance, is employed in order to disguise a terrible thing as a good one. Providing a run-down on her classes at college, where she studies animal husbandry, Karen gives us one of numerous examples of human idiocy, informing us that “the methods course on killing… animal species was called Meat Industry.” Throughout the novel, readers get the chance to experience Karen’s forthright, direct way of thinking, seeing and feeling the world, and this proves an excellent way to reconceive of our own “standard” modes of action and interaction through fresh eyes.

In addition to providing the narrator’s distinctive voice and unique perspective, Me… is also something of a novel of ideas. Berman examines the “I think, therefore I am” premise of Descartes—whom Karen detests—and contrasts him to Darwin, whom she loves. As a girl who spent the first dozen or so years of her life just “being” (she doesn’t learn to speak at all until she’s about twelve) and not “thinking,” Karen sees Descartes’ philosophy as the supreme expression of human self-centeredness, which leads humans to justify how many terrible things they do to just about every other species. Berman also explores what it means to possess “intelligence”. Karen, for instance, ranks somewhere “between imbecile and idiot” on IQ tests—although in terms of spatial organization she is in the top percentile, has a photographic memory, and can sketch blueprints like nobody’s business. But how and why is it that in order to be considered intelligent, what humans must learn to do successfully is lie, delude themselves and others, and distinguish themselves from the animal kingdom, which never lies?

Finally, Me… teaches readers a tremendous amount about tuna fish and the tuna industry, which is actually a much more fascinating topic than you might imagine. First, we learn the basics of actual fishing practices: how the boats cast mile-long, weighted purse-seines (a type of net) to surround the fish and force them into the tuna boats; how and why dolphins are trapped and then freed during the catch, though other types of bycatch are ignored; the US-Mexico tuna wars. And I challenge anyone to read the description of the kill and its aftermath and not rethink their own eating practices. (Personally, I have become purely a “cucumber roll” sushi consumer since first reading this novel.) Second, the book also delves into the ecological impact and the (lack of) sustainability of tuna fishing, and in particular bluefin tuna fishing. Life in Japan schools Karen—pun intended—in the astonishing cost and distinctions between grades of bluefin sushi and sashimi. It also exposes her to the darker side of animal rights activism. So while the book’s pro-animal stance is clear, it is by no means preachy nor does it let the other side “off the hook”, so to speak

For all of these reasons, translating Me… was thrilling. Putting myself inside Karen’s head to determine how I thought she might express herself in English was not only a challenge but an absolute joy.

17 August 2012 | in translation |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.