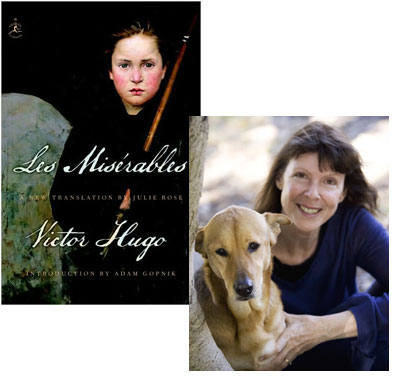

What Julie Rose Adds to Victor Hugo

When I began conceiving of the “In Translation” series of essays last year, one of the first translators I wanted to invite was Julie Rose, as her mammoth new English-language version of Les Misérables had just been released. I finally took the opportunity earlier this year, when I learned that she was among the finalists for the French-American Foundation’s annual translation prize; we began corresponding, and eventually a gap came up in her schedule (as she notes early on, she’s kept very busy translating modern French literature!) when she was able to share her thoughts on tackling Victor Hugo’s most famous novel. The appearance of this essay coincides with Rose’s first visit to the United States; in fact, if you follow Beatrice on Facebook, early next week you’ll get the inside scoop on a small gathering we’ll be having in New York City. I’m looking forward to meeting her in person, and I hope I’ll see some of you there!

I have four new translations out there on the shelves at the moment, all published in the last fourteen months.

The most mammoth of these is Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables, published by Random House (New York) and Vintage (London) in hardback last year—now out in paperback. At the opposite end of the spectrum is André Gorz’s slim but relentless letter to his wife of 58 years, Letter to D., published by HarperCollins (Australia) last year and by Polity Press in the US and UK recently; and French-born, Sydney-based Catherine Rey’s Stepping Out, an autobiographical portrait of the artist as a young—and not so young—woman, published by Giramondo (Australia) late last year.

The fourth book, Film World, is a collection of interviews with celebrated filmmakers recorded over decades by French film critic Michel Ciment. That was an interesting project, since Ciment had recorded a number of the interviews originally in English, which he speaks, before translating them into French. I then had to translate them back into English, without, in most cases, anything to go by, since the tapes had been trashed and most had never been published in English before. It was fun ‘playing’ 25 wildly idiosyncratic cinematic geniuses.

There would normally be a splendidly hybrid book by cultural critic Paul Virilio, as well. He turns out one a year and I’m never too far behind; though not yet out, University of Disaster is coming soon. And I’ve just finished a draft of an intricate theoretical work by Jacques Rancière, Politics of Literature. I myself am dazzled by the scope of this list of fabulous books. Hugo, Gorz, Rey, Ciment, Virilio, Rancière: writerly biodiversity in action.

Such a list presents vast differences in style, emotional register and temperament, context and resonance and intellectual tone—all those qualities that go to make the thing we call ‘voice’. Some people talk about texture, flavour, music, taste, colour. These are all sensory metaphors for the same thing. I prefer to call it ‘voice’ to suggest the theatricality not only of the embodiment of personality in writing in the first place, but the whole performance of re-embodiment that the process of translation entails. Translation is rewriting—as someone you imagine the writer to be.

A writer’s ‘voice’ in this sense is as unique as the thing produced by their vocal chords, no matter how codified shared language and the rules of writing might be. It is ‘voice’ that a translator worth her salt is always trying to mimic.

Translation as an art is an art of listening that means getting into ‘character’ and staying there, convincingly, from start to finish. In so doing, of course, you produce your very own distinct voice, with its very own timbres and energies. Which is one reason why re-translating is a potentially endless field. The original text stands immutable, but its potential translations are potentially infinite.

For me, there’s a golden rule here which is that, the more distinct that ‘second’ voice—the voice that you the reader, who needs the translation, receives—the more intensely and successfully I, who don’t need the translation, have managed to ‘get’ the original.

The ‘successful’ translation is the one where I, the translator, am completely invisible. A translator’s glory lies in their own disappearance. Nothing could be more satisfying. For others. Of course, every word is mine as much as his or hers. It is a double act, after all.

1 September 2009 | in translation |

Charlotte Mandell: Living Inside The Kindly Ones

The publication of Jonathan Littell’s The Kindly Ones has created what amounts to the biggest controversy among American book reviewers since Alice Sebold’s The Almost Moon—as with that book, it’s almost not enough to have an opinion about the story, you’re also compelled to formulate a moral argument for or against it as well. But what does the woman who’s probably read the novel more closely than anybody else in the United States have to say about it? I asked Charlotte Mandell, who translated the novel from the French, to discuss her reactions to the text as she was translating it, and she was kind enough to send this essay in response.

People talk about ‘free translation’—and they usually mean something that I’d judge sloppy or pretentious. For me, my real freedom as a translator is to follow strictly, alertly, joyfully, the moves and rhythms of the original text. I want the reader to know exactly what the author thought—and when he thought it. That means I want the translation to present ideas, images, events in as close as humanly possible to the order in which those ideas, images, events occur in the original. I want the reader to hear the author think.

And to do that, I have chosen to translate right from the start of the text: I do not read ahead. I don’t read the book before I translate it. I don’t want to know what it means before I go through the actual formation of its meaning word by word. In that way, I not only try to keep the reader in mind (so that if I come to a puzzling passage I can guess the reader will be puzzled too, and I’ll try to find the best words to make the passage clear), but I also have the tremendous experience of, so to speak, accompanying the author in the act of composition. I follow at his pace, and go through his discoveries.

(Of course, once I’ve finished my first translation, I revise extensively, so that I end up with three or four complete drafts of the text before I’m happy with the final version. I also save most of my research till the end. In the case of The Kindly Ones, Jonathan had generously sent me a DVD that included interesting archival material—recordings of Eichmann’s speeches, footage of some of the camps after they’d been liberated, articles that appeared during WWII—so I studied that after I’d finished my first draft.)

So as I started translating The Kindly Ones, I came right away at the opening phrase, Frères humains… human brothers. And while a lot of reviewers have (rightly enough) been reminded of Baudelaire’s “hypocrite reader, my likeness, my brother,” Littell’s first words themselves echoed the first words of one of the most famous of French poems, François Villon’s Ballad of the Hanged: “Human brothers who live after us / Don’t harden your hearts against us / but pray to God that He may pardon us.”

Villon’s poem speaks in the voice of a felon on the gallows. Littell’s use of this phrase, making it the first thing that Max Aue says, turns out to be a rich anticipation of two important themes in Aue’s account: confession and exculpation. Villon’s felons about to be hanged are guilty, that’s why they’re on the gallows, but they are our brothers, and need our compassion and forgiveness. So we can anticipate that Aue will be avowing his crimes—but also in a sense excusing them by appealing to what is finally a major premise of his story: There is no such thing as inhumanity, there is only humanity.

14 March 2009 | in translation |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.