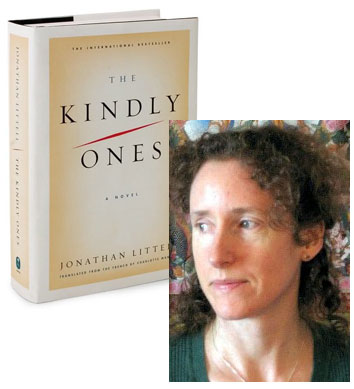

Charlotte Mandell: Living Inside The Kindly Ones

The publication of Jonathan Littell’s The Kindly Ones has created what amounts to the biggest controversy among American book reviewers since Alice Sebold’s The Almost Moon—as with that book, it’s almost not enough to have an opinion about the story, you’re also compelled to formulate a moral argument for or against it as well. But what does the woman who’s probably read the novel more closely than anybody else in the United States have to say about it? I asked Charlotte Mandell, who translated the novel from the French, to discuss her reactions to the text as she was translating it, and she was kind enough to send this essay in response.

People talk about ‘free translation’—and they usually mean something that I’d judge sloppy or pretentious. For me, my real freedom as a translator is to follow strictly, alertly, joyfully, the moves and rhythms of the original text. I want the reader to know exactly what the author thought—and when he thought it. That means I want the translation to present ideas, images, events in as close as humanly possible to the order in which those ideas, images, events occur in the original. I want the reader to hear the author think.

And to do that, I have chosen to translate right from the start of the text: I do not read ahead. I don’t read the book before I translate it. I don’t want to know what it means before I go through the actual formation of its meaning word by word. In that way, I not only try to keep the reader in mind (so that if I come to a puzzling passage I can guess the reader will be puzzled too, and I’ll try to find the best words to make the passage clear), but I also have the tremendous experience of, so to speak, accompanying the author in the act of composition. I follow at his pace, and go through his discoveries.

(Of course, once I’ve finished my first translation, I revise extensively, so that I end up with three or four complete drafts of the text before I’m happy with the final version. I also save most of my research till the end. In the case of The Kindly Ones, Jonathan had generously sent me a DVD that included interesting archival material—recordings of Eichmann’s speeches, footage of some of the camps after they’d been liberated, articles that appeared during WWII—so I studied that after I’d finished my first draft.)

So as I started translating The Kindly Ones, I came right away at the opening phrase, Frères humains… human brothers. And while a lot of reviewers have (rightly enough) been reminded of Baudelaire’s “hypocrite reader, my likeness, my brother,” Littell’s first words themselves echoed the first words of one of the most famous of French poems, François Villon’s Ballad of the Hanged: “Human brothers who live after us / Don’t harden your hearts against us / but pray to God that He may pardon us.”

Villon’s poem speaks in the voice of a felon on the gallows. Littell’s use of this phrase, making it the first thing that Max Aue says, turns out to be a rich anticipation of two important themes in Aue’s account: confession and exculpation. Villon’s felons about to be hanged are guilty, that’s why they’re on the gallows, but they are our brothers, and need our compassion and forgiveness. So we can anticipate that Aue will be avowing his crimes—but also in a sense excusing them by appealing to what is finally a major premise of his story: There is no such thing as inhumanity, there is only humanity.

In the same way, the curious name of the protagonist, Aue (which looks like the Latin word for hail or hello), certainly didn’t strike me immediately as German, but did seem vaguely familiar. Then memory works: Hartmann von Aue, the mediaeval German narrative poet, whose major poem, Gregorius, tells the story of brother-sister love, and their incest, from which a child is born who will go on to find himself, ignorant as Oedipus, years later in bed with his mother. This is, of course, the story that Thomas Mann renewed for our time in his late novel, The Holy Sinner. So meeting Aue’s name already makes the unconscious mind of the translator, and of the reader, stir with anticipations of incest and outrage—the very emotional core of The Kindly Ones, in fact.

I translated my way along, excitedly translating because I was excited by the reading; my agreement with myself that I have to translate as I read made me translate with the same eagerness a child reads an engrossing book. It becomes less an effort than a flight into the text, a journey into the story itself.

So the horrors that Max Aue encounters on the way surprise and shock me as I come upon them, but the shock of discovery becomes the shock of inscription: being shocked into saying these things anew in my native language. In reading through the more horrifying, scarifying parts of the book (Stalingrad, Auschwitz, the underground factories), the revulsion one feels at the gross descriptions is curiously checked, held in suspension, by the immense detail of bureaucracy and administrative chicanery.

Of course there are perils in my way of working, but they are perils the reader shares. For instance, at the outset I was taken in and moved at first by Max Aue’s refusal to apologize, or rather, couching his apologia as a broad statement about humanity, as if he were indeed our brother. But as I went along, I began to realize that his claim of being somehow a representative man actually amounts to Littell’s deepest indictment of him. Aue is not ordinary; he is weird, fated, an exile, a pervert, something of a monster. No ordinary Nazi would tell this story. We need a special kind of perpetrator. If evil were truly “banal” (even in the true sense of that expression: commonplace, ordinary, matter-of-fact), it would need an ordinary man to be the best mirror of it.

But the heightened sensitivity, the intellectual alertness, the keen legal intelligence, the intense sexual reverie of Max Aue—these are not ordinary, certainly not banal. He is the fiercely perceiving witness. What he sees is the horror of the Holocaust, the horror of war and brutalized infancy. And at every step of the way, he makes his moral choices. And that’s where we come in. We witness his choosing or his refusal to choose, and we have to confront his confrontations. Because we come to inhabit him (as we as readers are compelled to travel inside every first-person-narration), we have to make those choices too.

As Littell pointed out in an interview, we have heard the victim’s story over and over. Now we need to hear the perpetrator. We need to try and figure out his motives, his excuses. And what a perpetrator Max is—his keen aesthetic sense constantly lures us into his mind. And then again and again we have to make our own choices, our own abstentions. What a moral workout the book puts the reader through—and that is a large part of its greatness, and my own satisfaction in what could otherwise have been a horror show. This is not the One Good Nazi of the sentimental (and to me disgusting) movies. This is the Evil Nazi, and we are in him for a thousand pages, and have to make our own way out. No consolations, no forgivenesses. I think about Paul Celan’s famous question, and realize we have to become the ones who witness the witness.

14 March 2009 | in translation |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.