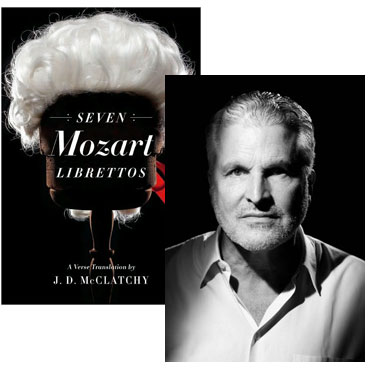

J. D. McClatchy on Translating Mozart’s Librettos

In Seven Mozart Librettos, the poet J.D. McClatchy translates (forgive me for being obvious here) the librettos to seven operas Mozart composed during the last decade of his life, aiming—as he writes in this essay, drawn from the nearly 1200-page volume’s introduction—to help readers “hear the verse, but listen to the drama.” My familiarity with opera in general, and Mozart in particular, is still fairly limited; I’ve only seen productions of two of the works included in this collection. But, as McClatchy notes later in the introduction, “perhaps the best way to read each opera is with a recording of it playing,” and since Mrs. Beatrice has a fairly decent collection of opera on CD, it looks like I’ve got a great opportunity ahead of me…

A libretto is not a poem or a play. It lacks the former’s structural intensity and elegance, and the latter’s depth and intricacy. It has a very specific non-literary function—to make the composer want to write music. Yet throughout opera’s history there have been librettos of superb finesse and polish. A great composer can make them into an unparalleled dramatic evening. But what is it that draws a composer—Mozart, say—to want to set a particular text?

One problem with the existing translations of Mozart’s operas is that, for all their earnestness or cleverness, often they don’t really give you what the characters are actually saying in the original, or they distort the tone of delivery. Take the opening lines of Don Giovanni, with the Don’s manservant Leporello impatiently waiting out in the cold while his master is enjoying a lady’s favors inside. The Italian goes this way, in a kind of shivering staccato that emphasizes each syllable:

Notte e giorno faticar,

Per chi nulla sa gradir;

Piova e vento sopportar,

Mangiar male e mal dormir.One of the more literal translations now in print translates this as

I work hard day and night,

And he never thanks me.

I endure winds and rain,

Poor food and little sleep.Granted, that is the gist of Leporello’s complaint, but hardly gives the flavor of his witty, if whiney, sense of life’s unfairness. Even the amateur can hear in the original the tetrameter line with its abab rhyme scheme, and pick up the sense of parallel pairs of terms (notte e giorno [night and day], piova e vento [rain and wind]). When W. H. Auden and Chester Kallman translated the opera in 1957, they wisely took a freer hand, and observed the Italian’s pattern of images and rhymes in a fluent English verse:

On the go from morn till night,

Running errands, never free,

Hardly time to snatch a bite;

This is not the life for me.One appreciates the slang (“on the go,” “snatch a bite”) that adds color to the moment and allows the singer to elicit a smile from the audience. But, presumably in an effort to add some background and prepare for what’s to come, the second and fourth lines here are entirely made up; and the problem is not that Leporello eats hurriedly, but that he eats badly. My own version tries to keep the verse scheme of the original as well as accurately carry over into English everything the Italian is saying, while still trying to brush up the character’s grumbling personality:

Always working, night and day,

And not a word of gratitude.

Wind and rain, come what may,

Never a nap, and rotten food.

29 December 2010 | in translation |

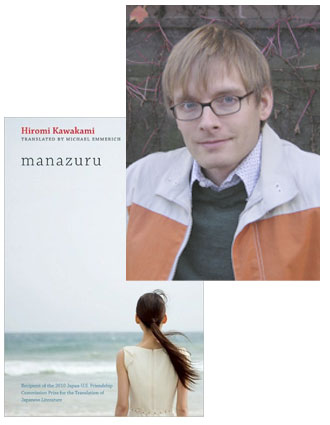

Michael Emmerich & The Manazuru Tuning Fork

The biggest reason for people in the U.S. to read more translations is that there’s a hell of a lot of amazing stuff being written… all around the world,” Michael Emmerich told The Quarterly Conversation a while back. “Most of us have, at least one point in our lives, come across writers or books that really changed the way we think, or feel, or what we like or something else about us. There are a lot of terrific writers working in English, of course, but there are even more writing in other languages. Who knows, maybe a book has already been written in some other place, in some other language, that would really change my life and the way I look at things, if only I knew about it?” It could even be that Manazuru, the latest of Emmerich’s translations of contemporary Japanese literature, could be that book. Hiromi Kawakami’s novel is a (haunting? unnverving?) story about a woman who’s still working through the disappearance of her husband twelve years earlier, drifting through her present relationships and occasionally becoming unmoored from the world around her. It’s not, as Emmerich explains in this essay, an easy novel to translate, but he’s found a very powerful solution.

From a translator’s perspective, not all books are equal. Some are a joy to translate, some are not. Some books seem to struggle with all their might against being rewritten in English, while others seem almost to have been waiting for a translator to appear, to complete a metamorphosis that has already begun, in some mysterious way, in the language of the original. It is not always easy to tell beforehand which type, or combination of types, a certain book will be: extremely difficult to translate and not at all fun, or difficult and rewarding, or easy and dreadfully dull.

Translating Hiromi Kawakami’s Manazuru was a startlingly easy joy. I remember that when I first read this novel, before there was any discussion of my translating it, I found myself thinking that it would be all but impossible to create an English echo of its terse, resonant, and subtly strange prose. Kawakami has a penchant for words that don’t sit easily in modern Japanese—classical vocabulary that feels slightly odd, that refuses to blend in, and yet somehow also feels precisely right. The Japanese language has a long history, and every so often Kawakami will use a thousand-year-old word that is recognizable, if it is recognizable, only because of the slight family resemblance it bears to a modern descendant. In Manazuru, Kawakami also uses unusual punctuation: she puts commas and periods in places where one would not normally expect to find them, and leaves out expected quotation marks. She also exploits to the full the inherent tendency of Japanese prose to drift effortlessly back and forth between what would usually be thought of, in English terms, as past and present tense.

Manazuru‘s prose was odd and wonderful. It urged readers to read slowly, and rewarded them if they did. A good translation, I thought, would have to create a voice in English that breathes the way the prose of the Japanese does. It would have to be quirky and unsettling, but at the same time convincing. It would be hard to pull off, especially given the culture of translation in the English-speaking world, in which many readers and reviewers seem to expect translations to be written in some fantasy “standard English.” In order to translate Manazuru effectively, one would have to create a voice in English so compelling, so alive, that even readers accustomed to faulting translators for each and every apparent “irregularity” in their English rewritings of foreign texts would be persuaded to accept the odd rhythms, startling word choices, peculiar punctuation, and sudden shifts in tense. They would have to be convinced to see the strangeness, not as a lack of smoothness, but as part of what makes this novel, Manazuru, so rich.

9 October 2010 | in translation |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.