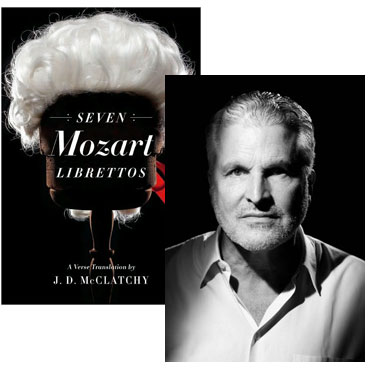

J. D. McClatchy on Translating Mozart’s Librettos

In Seven Mozart Librettos, the poet J.D. McClatchy translates (forgive me for being obvious here) the librettos to seven operas Mozart composed during the last decade of his life, aiming—as he writes in this essay, drawn from the nearly 1200-page volume’s introduction—to help readers “hear the verse, but listen to the drama.” My familiarity with opera in general, and Mozart in particular, is still fairly limited; I’ve only seen productions of two of the works included in this collection. But, as McClatchy notes later in the introduction, “perhaps the best way to read each opera is with a recording of it playing,” and since Mrs. Beatrice has a fairly decent collection of opera on CD, it looks like I’ve got a great opportunity ahead of me…

A libretto is not a poem or a play. It lacks the former’s structural intensity and elegance, and the latter’s depth and intricacy. It has a very specific non-literary function—to make the composer want to write music. Yet throughout opera’s history there have been librettos of superb finesse and polish. A great composer can make them into an unparalleled dramatic evening. But what is it that draws a composer—Mozart, say—to want to set a particular text?

One problem with the existing translations of Mozart’s operas is that, for all their earnestness or cleverness, often they don’t really give you what the characters are actually saying in the original, or they distort the tone of delivery. Take the opening lines of Don Giovanni, with the Don’s manservant Leporello impatiently waiting out in the cold while his master is enjoying a lady’s favors inside. The Italian goes this way, in a kind of shivering staccato that emphasizes each syllable:

Notte e giorno faticar,

Per chi nulla sa gradir;

Piova e vento sopportar,

Mangiar male e mal dormir.One of the more literal translations now in print translates this as

I work hard day and night,

And he never thanks me.

I endure winds and rain,

Poor food and little sleep.Granted, that is the gist of Leporello’s complaint, but hardly gives the flavor of his witty, if whiney, sense of life’s unfairness. Even the amateur can hear in the original the tetrameter line with its abab rhyme scheme, and pick up the sense of parallel pairs of terms (notte e giorno [night and day], piova e vento [rain and wind]). When W. H. Auden and Chester Kallman translated the opera in 1957, they wisely took a freer hand, and observed the Italian’s pattern of images and rhymes in a fluent English verse:

On the go from morn till night,

Running errands, never free,

Hardly time to snatch a bite;

This is not the life for me.One appreciates the slang (“on the go,” “snatch a bite”) that adds color to the moment and allows the singer to elicit a smile from the audience. But, presumably in an effort to add some background and prepare for what’s to come, the second and fourth lines here are entirely made up; and the problem is not that Leporello eats hurriedly, but that he eats badly. My own version tries to keep the verse scheme of the original as well as accurately carry over into English everything the Italian is saying, while still trying to brush up the character’s grumbling personality:

Always working, night and day,

And not a word of gratitude.

Wind and rain, come what may,

Never a nap, and rotten food.

Let me offer another example. Some years ago I was asked to translate The Magic Flute for a new artist’s book. When that edition appeared and came to the attention of stage director Julie Taymor, who was then directing a new production of the opera at the Metropolitan Opera, she asked if I would adapt my translation for the supertitles to be used on seatback screens. And when they proved successful, the Met then asked if I would create a singing translation in a shortened adaptation for holiday presentation. In the opera house and on television, that version has had a success of its own, and the English—along with Taymor’s brilliant stage pictures, and performances of the highest caliber—have brought many new viewers, particularly young ones, into the magical world Mozart created.

While I was working on these various versions, I was continually struck by the need to use English verse in a way to capture the charm of the German (Mozart’s native language but one he used only for comic operas) but also to be convincing as human speech. This is true not only in the famous set-pieces but in the give-and-take between characters. Looking back over older translations was sometimes dismaying. The standard English singing translation, used for years at the Met and elsewhere, was made by Ruth and Thomas Martin in 1941. At point early in Act One, the birdcatcher Papageno has had a padlock put on his mouth when The Three Ladies caught him telling lies. Papageno turns to his new friend, the prince Tamino, and tries to get his help. Here is their exchange—and the moment of his release:

PAPAGENO (points sadly to the padlock on his mouth)

Hm! hm! hm! hm! hm! hm! hm! hm!TAMINO

The poor young lad must surely suffer,

He tries to talk, but all in vain!PAPAGENO

Hm! hm! hm! hm! hm! hm! hm! hm!TAMINO

I can no help or comfort offer.

I wish I could relieve your pain.(Enter the Three Ladies.)

FIRST LADY

The Queen forgives you graciously.

(removes the padlock)

From punishment you shall be free.PAPAGENO

Oh, what joy again to chatter!SECOND LADY

Be truthful, and you will fare better!PAPAGENO

No lie shall ever come from me.THE THREE LADIES

This padlock shall your warning be!In their 1955 translation, Auden and Kallman, having changed the order of scenes and fussily manipulated the opera’s tone and ambitions, had Tamino say to Papageno instead:

His wits, by lack of words unwitty,

Express what he is sentenced to:

By words I can express my pity,

But that is all my words can do.Neither version satisfies, either as verse or as speech. My Tamino first observes from a distance:

The poor man’s punishment is plain.

His tongue is under lock and key.Then, having himself been put under an order of silence, he addresses his friend:

I sympathize but can’t explain,

And have no power to set you free.When the First Lady returns to remove the padlock, the scene continues:

FIRST LADY

The Queen has heard your mumbled plea

And bids us lift her stern decree.

(She removes the padlock.)PAPAGENO

At last! Again! A chatterbox!SECOND LADY

Another lie, and double locks!PAPAGENO

I’ll never tell another lie!THE THREE LADIES

This lock should warn you not to try!Verse will always draw attention to itself, but it needs first of all to draw a reader into the scene and the character, and in ways that may astonish but must always convince. What sounds smart and chiseled in one era may sound stiff and contrived in the next. My own versions, which admire the classical restraint and technical virtuosity of the original texts, strive to appeal to contemporary ears, but to a pair that is familiar with the poet’s task and with the great tradition of memorable verse. I want the reader to hear the verse, but listen to the drama.

29 December 2010 | in translation |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.