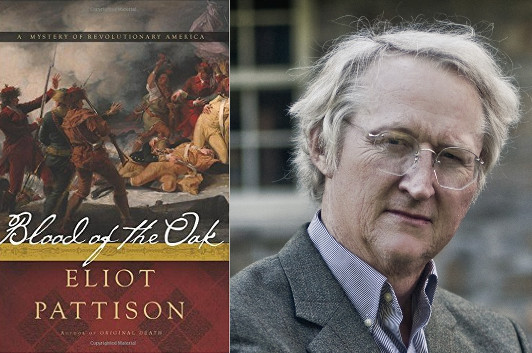

Eliot Pattison: The Power of the Historical Novel

photo: Ted Ferguson

If you’re a fan of hardboiled detective fiction, I’ve got a left-field recommendation for you: Eliot Pattison‘s Blood of the Oak is a historical novel, set in pre-Revolutionary America. It’s the fourth novel in a series featuring Duncan MacCallum, who came to the colonies as an indentured servant but now lives on the edge of Britain’s penetration into the New World. In this story, he’s compelled by both a request from a dying Iroquois friend and an attack on a British comrade to investigate a series of brutal murder and, much like our modern private eyes and single-minded police, slowly but surely finds himself wading into deep tides of corruption and evil. I’m as engrossed by this plot as I’ve ever been by a Robert B. Parker or Michael Connelly novel, and Pattison’s fantastic at making 1760s America feel simultaneously strange and familiar. Which, as he explains in this guest post, is something he works hard to accomplish…

America has misplaced her history. Studying our past has been dropped from many required curricula in our schools, and our students score lower in history than any other subject—which should come as no surprise to anyone who has turned the sterile pages of modern texts. Those pages squeeze the life out of history, rendering it an arid dump of dates and statistics, as if the story of mankind were just a scientific experiment of interest only to technicians.

But we are not composed of dates and data, we are not constructed of factoids to be reduced to graphs and charts. The DNA that makes us possible was bestowed on us by people who lived incredible lives, who endured unspeakable adversities, engaged in staggering adventures, suffered abject tragedies and celebrated boundless joys. We all swim with them in the same great ocean of humankind, separated not so much by beliefs, appetites, and interests as by technology and time.

Stories of our forebears and tales of the struggle to be human have been a vital part of every culture. They are part of our spiritual DNA, and our institutions have failed us by ignoring them. We are diminished by losing that connection with our ancestors. Our cultural gurus preach self-awareness but how can we be self-aware if we don’t even understand the legs we stand on? If you don’t know history, novelist Michael Crichton once observed, “you’re just a leaf that doesn’t know it is part of a tree.” We have historical novels because our history books and our history classrooms are just not good enough.

27 March 2016 | guest authors |

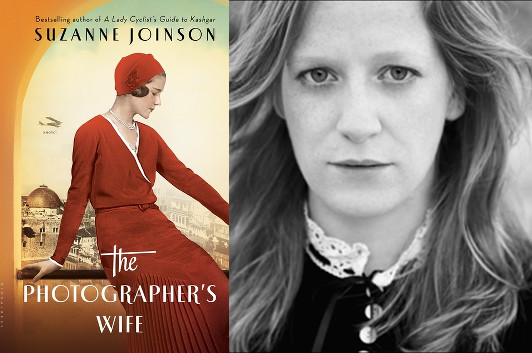

Suzanne Joinson’s Writing Takes Wing

photo: Simon Webb

I first met Suzanne Joinson back in 2012, when Bloomsbury held a reception to introduce her to book review editors and literary journalists shortly before the publication of her first novel, A Lady Cyclist’s Guide to Kashgar. When I found out recently that she had a new book, The Photographer’s Wife, coming out, I was eager to read it, and I’m happy to report that I’m currently riveted by the story of 11-year-old Prue, the daughter of an English architect who’s in charge of an ambitious development project in Jerusalem in the year 1920, and how she gets caught up in the intrigues of the adults around her—and, then, seventeen years later, back in England, some of those mysteries return to intrude upon her life in decidedly unwelcome ways. It’s still early stages for me, and I’m not quite sure how it’s going to turn out, but I’m looking forward to learning. Meanwhile, in this guest post, Joinson talks about what it took for her to be able to arrange her day-to-day reality in such a way that she could create this vivid world of imagination.

What must it feel like to be a wingwalker? Balancing on the wing of an aeroplane as it loops and swoops in the bright blue sky? The idea for The Photographer’s Wife came to me in the middle of a windy airfield at a vintage bi-plane show. The crowd went crazy when the brave wingwalkers appeared in their blue and yellow costumes, blazoned with their sponsor’s logo: UTTERLY BUTTERLY: I CAN’T BELIEVE IT’S NOT BUTTER! All young, glamorous women, they looked like cheerleaders from another era as they climbed into insane contraptions on the top of the aircrafts.

In the end there are no wingwalkers in my book, nor is there a reference to my day of standing in the airfield, but it was the beginning. Shortly after, I organised becoming a writer-in-residence at a 1930s art deco airport in Shoreham, England where I rummaged in the not-very-well-kept archives. I found secrets and letters and photographs of pilots who were given five hours flight training and then sent to far-off cities: Salonika (now Thessaloniki), Jerusalem, Cairo. A story grew in me, coming up from the bones of the land, about the place as well as the people, driven by my desire to understand its web of connections across the world.

11 February 2016 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.