What Sara Shepard Talks About When She Doesn’t Want to Talk About Her New Novel

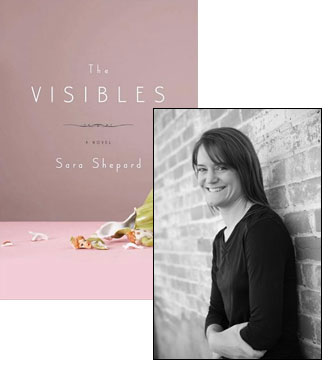

I’m still in the middle of—and very much admiring—The Visibles, the first “adult novel” by Sara Shepard, a writer who already has a strong track record with YA fiction. In fact, when I first approached her to write an essay for Beatrice, I suggested she discuss her transition from one market to the other—and though she gave that subject a go, what she ultimately found herself writing was something much more personal.

Those who have read The Visibles often ask, “What inspired you to write this story?” It’s a fairly common question—I get it for my young adult novels as well—but this time around, it trips me up. The information I think a lot of people are looking for makes me uncomfortable. The Visibles is about a girl coming of age in Brooklyn and Western Pennsylvania, DNA, secrets, prejudice, cancer, and depression—and the depression part of the novel springs from incidents in my own life. But it’s not exactly something I want to get into.

Fiction and memoir are two different things, obviously, but as a fiction writer, I can’t help but draw from what I’ve experienced firsthand. When reading someone else’s novel, I similarly wonder why the author chose to go in such-and-such direction, when there are so many avenues from which to choose: Is it because she’s drawing from her experiences? Did she have a husband who fathered a child with someone else? Did she have a wayward brother who’d been molested by a family friend? It’s not always the case, of course: I’ve written enough fantastical plotlines—in my young adult series, Pretty Little Liars, anything from student-teacher affairs, near-fatal blindings, hit-and-run accidents, and appearing and disappearing dead bodies prevail—to know that events need not happen to you for you to make them your own. You approximate, you empathize, you work the passage over and over until it feels right. The nut of The Visibles didn’t emerge from some sort of cosmic abyss in a bolt of blind inspiration, though—it emerged from a personal experience. Something I’m reluctant to talk about when someone asks me that question after they’ve read the novel.

I was very close to it back when I was writing the first draft of The Visibles. Back then, the book was set in the Outer Banks of North Carolina, and Summer Davis, the main character, was in her thirties with two children, teaching biology and falling in love with an awkward but precocious student. Flashbacks to Summer’s previous life in New York, caring for her ailing father, kept poking their way in, invading each passage. The flashbacks, which related to my own life and were probably a therapeutic way by which to work it out, began to take over the novel, more or less stealing the show. I used up all my energy to write them; I took a week off work to pound out the flashback section so that I could be done with it and never return to it again. Following Summer’s flashback to its end was cathartic. I’d written it down; I’d gotten it out of my system.

14 June 2009 | guest authors |

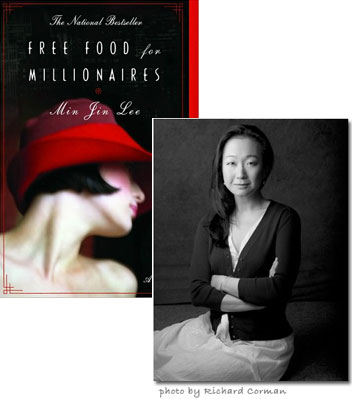

Min Jin Lee: Discovering America’s Communities in Fiction

As part of the Beatrice tribute to Asian Heritage Month (see the end of this post for full details), Min Jin Lee was kind enough to let me reprint this essay, which appears in the paperback edition of her debut novel, Free Food for Millionaires.

My parents, sisters, and I immigrated to Queens, New York, in March of 1976. My family was sponsored by my uncle John, a computer programmer at IBM. I was seven years old—two years older than my main character, Casey. Also, like her, I grew up in Elmhurst in a blue-collar neighborhood. We lived in a series of shabby rented apartments for the first five years, and then my parents bought a small three-family house in Maspeth and rented out the other two floors while we lived on the second floor. I learned how to speak English and to read and write in the public schools of Elmhurst and Maspeth, Queens. My sisters and I were latchkey kids. Our summers were spent working in our parents’ wholesale jewelry store and hanging out at the Elmhurst Public Library.

I could not have articulated it in this way then, but my childhood was continually informed by immigration, class, race, and gender. This book features first-and second-generation immigrant characters, and therefore, I believe that it satisfies the definition of an American story because unlike any other country in this world, America has this generative quality due to its immigration policies and early colonial history. With the exception of Native Americans and descendants of slaves, in the United States everyone’s biography is ultimately connected to an immigrant’s journey.

I was a history major in college, and my senior essay was about the colonization of the eighteenth-century American mind. Quite a mouthful. My argument then was that original American colonists from England and the generations that followed felt profoundly inferior intellectually and culturally to Europeans and those back home in their motherland. That idea has affected how I see my own challenges in America as an immigrant. I am not legally colonized—far from it—but an immigrant is like an early colonist (a word currently out of favor), that is, a person who has come from somewhere else, who learns to adapt to her new land with all its attendant complexities with an overall wish to acquire new “territory.”

It is an interesting position to consider since I am venturing to make culture—my crayon drawings of what I see and notice—in the form of fiction. I can be critical of how this country works, but I also respect its ideals of rugged individualism, the Protestant work ethic, and the American entrepreneurial spirit. It is easy to criticize America, but from a global perspective this is an amazing country with tremendous openness. This comment has been made before, elsewhere, by many pundits, and I think it is worth considering: Many who criticize America would still prefer to live here rather than anywhere else. Carlos Buloson, the Filipino American author, titled his rich novel America Is in the Heart. To me —another immigrant from a later time—I, too, possess a complex America in my heart.

Having said that, if you honestly love any object or subject, you will ultimately need to admit to its flaws in the hopes of some idealized love. We recall America’s checkered backstory: the near-annihilation of Native Americans, enslavement of African Americans, Jim Crow legislation, gender inequality, immigration quotas for people from southern Europe, the Chinese Exclusion Act, the internment of Japanese Americans, America’s reluctance to entering World War II, Hiroshima, McCarthyism, Vietnam, and the list continues. And thus, we recognize with both shock and compassion how with every generation, America has transferred its set of insecurities and anxieties to the newcomer.

27 May 2009 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.