Min Jin Lee: Discovering America’s Communities in Fiction

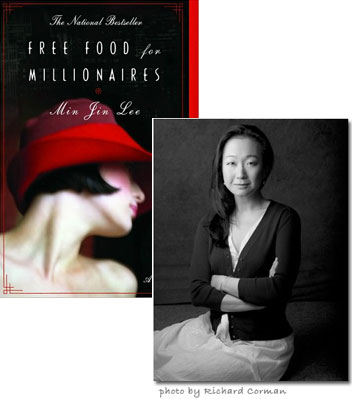

As part of the Beatrice tribute to Asian Heritage Month (see the end of this post for full details), Min Jin Lee was kind enough to let me reprint this essay, which appears in the paperback edition of her debut novel, Free Food for Millionaires.

My parents, sisters, and I immigrated to Queens, New York, in March of 1976. My family was sponsored by my uncle John, a computer programmer at IBM. I was seven years old—two years older than my main character, Casey. Also, like her, I grew up in Elmhurst in a blue-collar neighborhood. We lived in a series of shabby rented apartments for the first five years, and then my parents bought a small three-family house in Maspeth and rented out the other two floors while we lived on the second floor. I learned how to speak English and to read and write in the public schools of Elmhurst and Maspeth, Queens. My sisters and I were latchkey kids. Our summers were spent working in our parents’ wholesale jewelry store and hanging out at the Elmhurst Public Library.

I could not have articulated it in this way then, but my childhood was continually informed by immigration, class, race, and gender. This book features first-and second-generation immigrant characters, and therefore, I believe that it satisfies the definition of an American story because unlike any other country in this world, America has this generative quality due to its immigration policies and early colonial history. With the exception of Native Americans and descendants of slaves, in the United States everyone’s biography is ultimately connected to an immigrant’s journey.

I was a history major in college, and my senior essay was about the colonization of the eighteenth-century American mind. Quite a mouthful. My argument then was that original American colonists from England and the generations that followed felt profoundly inferior intellectually and culturally to Europeans and those back home in their motherland. That idea has affected how I see my own challenges in America as an immigrant. I am not legally colonized—far from it—but an immigrant is like an early colonist (a word currently out of favor), that is, a person who has come from somewhere else, who learns to adapt to her new land with all its attendant complexities with an overall wish to acquire new “territory.”

It is an interesting position to consider since I am venturing to make culture—my crayon drawings of what I see and notice—in the form of fiction. I can be critical of how this country works, but I also respect its ideals of rugged individualism, the Protestant work ethic, and the American entrepreneurial spirit. It is easy to criticize America, but from a global perspective this is an amazing country with tremendous openness. This comment has been made before, elsewhere, by many pundits, and I think it is worth considering: Many who criticize America would still prefer to live here rather than anywhere else. Carlos Buloson, the Filipino American author, titled his rich novel America Is in the Heart. To me —another immigrant from a later time—I, too, possess a complex America in my heart.

Having said that, if you honestly love any object or subject, you will ultimately need to admit to its flaws in the hopes of some idealized love. We recall America’s checkered backstory: the near-annihilation of Native Americans, enslavement of African Americans, Jim Crow legislation, gender inequality, immigration quotas for people from southern Europe, the Chinese Exclusion Act, the internment of Japanese Americans, America’s reluctance to entering World War II, Hiroshima, McCarthyism, Vietnam, and the list continues. And thus, we recognize with both shock and compassion how with every generation, America has transferred its set of insecurities and anxieties to the newcomer.

With all this in mind, I wanted to chronicle the personalities and issues that abound in my village of New York in the form of a novel, because I wanted to reveal these images and thoughts to myself and, hopefully, to my reader. I was profoundly affected by nineteenth-century European novels when I was growing up, and in college, I had the opportunity to read American novelists like Sinclair Lewis, Ernest Hemingway, James Baldwin, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, and Edith Wharton, among others, who made me realize that what you saw and wondered about should be reflected in a literary work with an eye toward integrating emotion, history, insight, and narrative shape.

There are many kinds of immigrants. When I was growing up in Queens, the immigrants were German, Polish, Irish, Greek, Italian, and Hungarian, as well as Chinese, Korean, and Indian. One of the interesting and perhaps obvious aspects of being a non-white immigrant is that an Asian American cannot “pass” as a member of the majority group as long as his or her phenotypical features remain racialized. Simply put, if your eye shape, nose, hair texture, or your physical body type reflect a distinctiveness compared to the ones belonging to the majority group—for good or for bad—full assimilation may not be possible. This can cause all sorts of interesting problems to crop up even in an open place like America.

Some have argued persuasively that racial minorities may always be immiscible with the majority. Naturally, this theory may cause consternation to many who wish to be a member of the majority culture with all its privileges and responsibilities. In this book, I handed my characters all sorts of gifts: education, good appearances, talents, strong family structures… and I wanted to see what they would do with their ambitions. They also received trials and caused some troubles of their own. Would race, class, immigration, and gender politics affect them? Or you might ask, how could they not? I wanted to know very much what would happen, too.

I believe that the dearth of accurate representations of Asian Americans in the media and in the arts has led to a misrepresentation of Asian Americans. Very often Asian Americans are perceived as highly competent, hardworking, and non-belligerent – that being the “positive” image—or they are represented as devious, inscrutable, and megalomaniacal. Whichever way it is done, these images do not fully represent the Asian Americans I know. If an Asian American, or anyone for that matter, is not given a voice and language with clear expression and evidence of feeling, his humanity is denied. What separates us as humans from machines or animals is our ability to feel, to express, to wonder, to yearn, to regret… I believe that the absence of accurate reflections is effectively a kind of social erasure with grave psychological consequences. The difficulty, however, is in discussing that which is not seen. In my attempt at the community novel, I wanted very much to reveal the complicated individuals who make up the Korean Americans I know. As a writer, I wanted to place the same demands on my non-Korean-American characters as well.

Forgive me for stating what may be to many of you the obvious: A Korean-American man can be romantic, passionate, loving, funny, and he can be troubled, sad, and frustrated. He can be all those things and so much more. A Korean-American woman can have existential questions about her world. He can be afraid. She can be heartbroken. It was extremely important to me that the Korean-American men and women I know and love in my life were given a fair shake in terms of their complexity. I have known Korean men who listen to opera, write poems, worry about losing their hair, and would give every cent in their pockets to their friends. I have seen Korean women ruin their lives through too much sacrifice or self-sabotage. I wanted men and women like that in my story.

It is an ever-present concern for me that in our collective wish to succeed and assimilate, we, as Korean Americans, will not make trouble or not say what we think or feel. That silence or deferral until the time is safe permits others to interpret our characters and lives for us. I cannot speak accurately for all Korean Americans. This book is clearly one person’s limited point of view. Nevertheless, I love being Korean American, and I love my family, my communities, and my history. This love was a kind of filter and a kind of bias. I wanted to honor what I know by telling it as truthfully as possible—with all its flaws and with all its beauty. My goals for this novel were embarrassingly lofty, but at the minimum I wanted the characters to be imperfect and to be gifted, too, because I believe that is how we are all made.

Lastly—but I think, for me as a fiction writer, most importantly—I want to share with you that for all of my life, for as long as I can remember, I have loved to read. A writer is always a reader first. Throughout my life, what has consistently given me great consolation was being able to read. When I studied how to write fiction better, my models were always the books I wanted to read again and again.

Beatrice is helping Hachette Book Group celebrate Asian Heritage Month by running a giveaway of five books by Asian-American authors—in addition to Min Jin Lee, there’s books by Kim Sunée, Jennifer 8. Lee, Frances Hwang, and Ronald Takaki. If you keep an eye on the Grand Central Publishing Twitter stream, later today they’ll ask readers to contact them with the secret word, and the first ten to respond will receive a set of books. For Wednesday, May 27, that secret word will be: “Elmhurst.”

(Note: U.S and Canadian readers only. Neither Beatrice nor Hachette Book Group is responsible for any technical difficulties that may occur when entering the giveaway.)

27 May 2009 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.