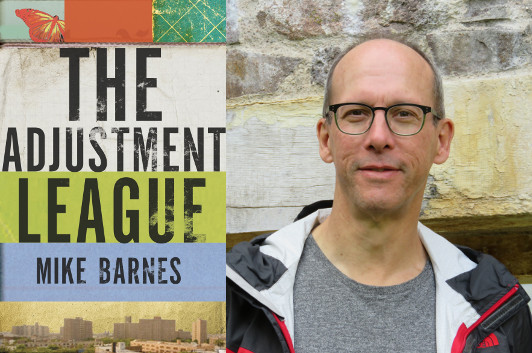

Mike Barnes: A Room in the Dark

photo: Segbingway

As I was reading the opening chapters of Mike Barnes’ The Adjustment League, I was reminded of the private eye novels I’d read in my formative years, real classic hardboiled stuff. Obviously, I knew that wasn’t accidental, but I could also see that wasn’t all there was to it—in addition to the surface familiarity of the genre conventions, there was also this very surreal, almost abstract quality to the first-person narration and the way it depicts the novel’s Toronto setting. The closest thing I can think of to describe it is Godard’s Alphaville, but that’s not really right, because this isn’t a science fiction novel… Anyway, as this guest essay reveals, what I was picking up on was something Mike Barnes had very much in mind as he was writing… and yet, in some ways, it caught him off guard as well.

Why do you write? It’s not a question I’ve given much thought to, in part because the answers seem either obvious or unknowable. Why did the chicken cross the road? The possibilities are endless, and the chicken might just be the last to know.

One reason I’m sure of, though, since it’s grown steadily stronger over time: I write to be surprised. By now, in fact, I lose interest quickly if I sense that what I’m writing isn’t likely to ambush me with things I didn’t know before, or didn’t know I knew. I crave these jolts of breaking news about myself, about writing, about the world.

The Adjustment League was a particularly rich source of such whacks upside the head. Here are a few of the revelations, big and small, it led me to.

13 April 2017 | guest authors |

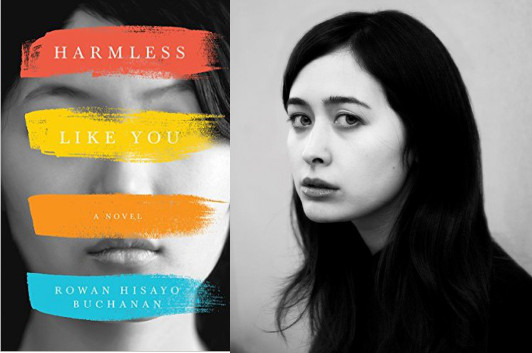

Rowan Hisayo Buchanan’s “NYC Novel”

photo: Eric Tortora Plato

It’s funny: I wouldn’t have thought of Rowan Hisayo Buchanan‘s Harmless Like You as a “New York novel,” exactly, even though, as she concedes in the essay below, a good part of the novel is set there, nearly half a century in the past. Part of my thinking is that it’s such a strongly character-driven novel, but that’s not to say there’s no strong sense of place, because Buchanan’s New York feels very authentic, even though it’s before my time as a New Yorker. Perhaps that’s because of how diligently Buchanan makes her characters, especially Yuki, pay attention to the world around them—the world becomes authentic through her eyes.

A few days ago, a friend called Harmless Like You a New York novel. The book is set in New York, Connecticut, and Berlin, but New York wins by page count. Still, I recoiled inside. I sipped my coffee and tried to keep a reasonable face. A New York novel. The phrase sounded smug as a young banker clinking his martini in a midtown bar. Could I have written such a thing? I just wanted to tell a story about a Japanese American woman who wants to be an artist and who leaves her son.

My first New York was a dream. I was born in London, a city almost as large, and just as written about. My dream New York didn’’t come from Audrey Hepburn standing outside Tiffany’s or the glossy I <3 NY sign. My New York was passed down to me by my mother. It was a home that she missed and I think, by telling stories, she rebuilt the city in our kitchen. It was the New York where she’d played with the Catholic kids and wandered into Mass by mistake. It was the New York where, as a little girl, she’d sat with Greta Garbo on a park bench. It was the New York where her mother left her in the Metropolitan Museum with museum guards for babysitters.

When I was eighteen, I moved to New York. I walked the Brooklyn Bridge eating lychees on a hot August night. I fought with a friend and sat out on his fire escape to sulk. Slowly, I stopped thinking of these scenes as New York moments. They just became moments. I had a grocery store, a bodega, a subway stop that I thought of as mine.

20 March 2017 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.