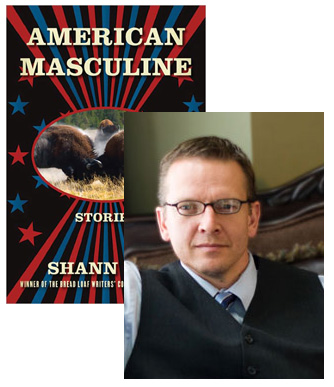

Shann Ray & the Phenomenology of Love

Shann Ray‘s short story collection, American Masculine, is the winner of this year’s Bakeless Prize, presented annually by the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference to support emerging writers. (Last year, I featured a poem by the previous winner, Nick Lantz.) These are some fantastic stories; Ray’s reflections on how we face the raw, brutal hurts life can throw us are never completely dispassionate, but a collection of stories entirely like “The Great Divide” would be hard to take, which is why I’m glad for the optimistic flashes in “How We Fall” or “When We Rise” (which is not to say these latter stories are especially cheery). In this guest essay, Ray tells us about another author who could convey with precise detail the effect of an intense emotion like love on the human spirit.

Some poets, for a time, are lost to us.

Elizabeth Barrett Browning was lost to me, and it was only after some years I found her again in her Selected Poems, a book issued in the Library of Classic Poets series (Gramercy/Random House, 2001). Born in 1806 at Coxhoe Hall, Durham, England, she was the first of twelve children. By ten years old she had read passages from Paradise Lost and a number of Shakespearean plays, among other great works. By the age of twelve she had written her first “epic” poem, composed of four books of rhyming couplets. Yet by fourteen Elizabeth had developed a lung ailment that plagued her for the rest of her life. Doctors administered morphine, which she took until her death. At fifteen, she also suffered a spinal injury.

Despite her physical setbacks, her mind continued to bloom and she consistently sought to bring healing to others through her writing. During her teens she taught herself Hebrew in order to better read the Old Testament. Later she turned to Greek studies, and her appetite for the classics was matched by a passionate Christian faith. At age twenty Elizabeth anonymously published An Essay on Mind and Other Poems. At twenty-two her mother died, affecting her deeply. The ongoing abolition of slavery in England and financial misdirection cut into her father’s income, and in 1832, he sold his estate and moved the family to a coastal town, before settling permanently in London. While living on the coast, Elizabeth’s translation of Aeschylus’ Prometheus Bound(1833) was published.

As her work gained greater audience in the 1830s, Elizabeth stayed in her father’s London house under his tyrannical rule. He began sending her siblings to Jamaica to help with the family’s estates there. Elizabeth bitterly opposed slavery and did not want her brothers and sisters sent away. With her health waning she spent a year at the sea of Torquay accompanied by a favorite brother Edward, whom she called “Bro.” He drowned while sailing at Torquay and Elizabeth came home emotionally bankrupt. Her next five years were spent as an invalid and a recluse in her bedroom at her father’s home.

In the face of despair she continued writing, and in 1844 produced a collection entitled simply Poems. In one of the poems Elizabeth had praised the poet Robert Browning, and he wrote her a letter. Together over the next twenty months the two exchanged 574 letters. Their love was directly opposed by her father, a man who wanted none of his children to marry. In 1846, Robert and Elizabeth eloped and settled in Florence, Italy, where Elizabeth’s health improved and she bore a son, Robert Wideman Browning. Her father never spoke to her again.

27 June 2011 | guest authors |

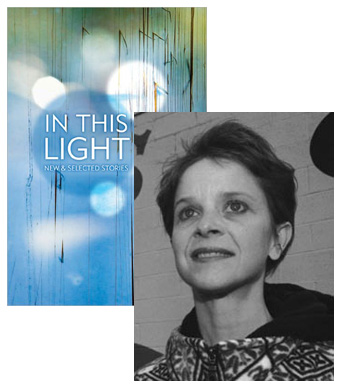

What Melanie Rae Thon Found in John Berger’s Pocket

In This Light takes some of the best short stories from Melanie Rae Thon’s first two collections, then adds three previously uncollected pieces—stories where plot, while not completely abandoned, matters less than a totality of experience. The narrators may not be literally unstuck in time, as Billy Pilgrim was in Slaughterhouse-Five, but their narration shifts between past and present without warning, taking on others’ perspectives without hesitation, as the telling of traumatic moments spirals out to encompass entire lives. I’d asked if Thon would be willing to contribute a guest essay to the “Selling Shorts” series, as I do with other short story writers, but instead she’s revealed how an essay by John Berger has changed the way she sees the world—and, I sense, the way she describes the world in her fiction.

There is no happiness like mine. I am reading John Berger’s The Shape of a Pocket, opening a gate, entering the interstices between my own sensory experience and other possible visible orders, perhaps ones “destined for night-birds, reindeer, ferrets, eels, whales… ”

In the fast flicker of daily perception, we sometimes sense the space between two frames, see or hear or smell in ways that give us a glimpse of life beyond our human limitations. Dogs, he says, are the “natural frontier experts of these interstices.” And no wonder! The average dog has over 200 million scent receptors in its nasal folds, compared to a human being’s 5 million. With mobile ears capturing and funneling sound, a dog can locate and identify the source in six-hundredths of a second. They have co-evolved with humans, learned to communicate with us, to seek our companionship and approval, while staying attuned to a river of sensory stimuli we can only begin to imagine. We train them as rescuers and guides; we trust they will save us.

Berger’s elegant essay gives me new appreciation and wonder as I walk along the river with my own beautiful Talia. She bounds ahead of me, a narrow slash of animal. All these years she’s been trying to teach me what she knows about the world. She senses the white hare sitting still in snow, ears twitching. The great horned owl watches us. He’ll kill a dog, a cat, a skunk, a porcupine—rip the hide off a fallen cow, snatch a coyote. Nothing is beyond his grasp: only the whirling hawk or a congregation of crows makes him flee in frenzy.

16 May 2011 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.