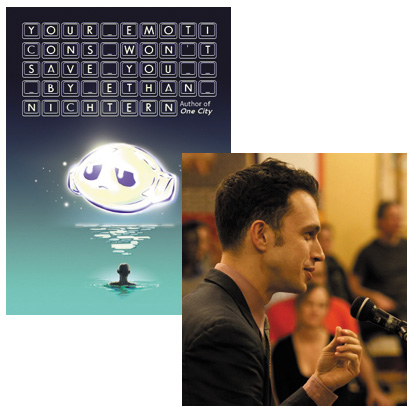

Ethan Nichtern: Poets Are Better Than Poetry

When I got a look at Ethan Nichtern‘s “short novel with poetry” Your Emoticons Won’t Save You, I was intrigued by the notion of writing poems from the perspective of the novel’s main character, so I approached Ethan and asked if he’d be interested in doing a guest essay for Beatrice. He takes a very personal approach to that topic, one that touches upon his own introduction to poetry as a child, and the personal connections he’s made with it as he’s gotten older.

Confession: I like poets more than I like poetry. Always have. My first formal poetry lesson came from Allen Ginsberg, when I was about nine years old. Allen studied with the same Buddhist teacher as my parents. He invited a handful of kids from the community to his East Village apartment and led us through some writing exercises and songs. Of course I had no idea who he was, except for a sweet old dude named “Allen.” I don’t remember much of what he taught; I hadn’t read a word of his writing. I remember his kind demeanor, his fearlessly bad singing voice, his soft gaze of a wild uncle at his kitchen table, and the old-style overhead-chain toilet in his bathroom.

Later, in high school and college, when I actually started to fancy myself a “Wannabe” Poet, I finally read Ginsberg’s work in depth, appreciating the ways his lyrics churned, the way he painted with words, the way his thoughts effervesced out onto the page. But mostly I remembered our few interactions before his death in 1997, and his figure in his apartment, a portrait etch-a-sketched in my mind. Since then, I’ve been around my fair share of poetry and my fair share of poets, both of the written and the performance variety. Something interesting always happens to me when I encounter a poet’s work. If I know the person and know a little of what makes them tick, I find myself leaning into their language with laser-like focus. If I don’t know them, if I haven’t inhabited their life at all, I find my interest in their work waning quickly. Poets, it seems, “do it” for me much more than Poetry.

I wrote a nonfiction book on contemporary Buddhism, One City: A Declaration of Interdependence. It was published in 2007, and was well received, but I always considered poetry and fiction to be, for me, the most resonant realms for exploring all the nooks and crannies of the mind’s wisdom and the heart’s confusion.

Your Emoticons Won’t Save You follows Alex Bardo, the self professed CEO of the Wannabe Poet’s Brigade, through a nostalgic road trip back to an old summer-camp at the end of the summer of 1998, as he’s going on 21 years old. Multiple forms of loss—as well as a tragicomic sense of just plain being lost—converge on him throughout the narrative. He uses poetry, or more precisely, his ironic identity as a Wannabe Poet, to cope with the space of transition in which he lives. For him, the act of writing poetry is one part narcissistic meditation and one part savior of sanity.

For every Actual Poet I have ever met, I have met 1,000 Wannabe Poets. Wannabe Poets do it for me even more than Poets. Wannabe Poets scribble on napkins and press our pen way too hard into those 99-cent camouflage journals. We open WordPress accounts in fits of inspiration and then forget to post anything for months. Wannabe Poets compose horrible love poems when someone breaks up with us, and even more horrible poems when someone returns our text message flirtatiously. Wannabe Poets forget to write anything at all when someone we love dies. We get depressed by failure and solemnly vow to never write again, then wake up the next morning and start scribbling on the closest piece of paper we can find. Wannabe Poets are a dime a dozen (less with inflation), and we even get off a little bit on the cliche of just how ludicrously numerous we are.

Your Emoticons Won’t Save You ends with 12 poems, authored by the novel’s protagonist over the next decade of his life, as life and love and loss have seasoned him a little bit toward that overrated state called maturity.

The premise of Your Emoticons Won’t Save You follows from my early experience with poetry, beginning with sitting in Allen Ginsberg’s apartment as a nervous nine year old. The idea is that if you get to know a poet first through reading his story, you will be more likely to want to read his poetry. Or, in Alex Bardo’s case, the idea is that if the reader gets to know a Wannabe Poet, you will want to read his Wannabe Poetry.

Updated Confession: I like Poets more than I like Poetry—and I like Wannabe Poets even more.

1 March 2012 | guest authors |

Leslie Brody & The Inspiration of Jessica Mitford

You know, we haven’t had a biographer drop by Beatrice in a while, so I’m delighted to share this essay from Leslie Brody about what led her to write Irrepressible: The Life and Times of Jessica Mitford and the inspiration she drew from her subject. I confess I haven’t had a chance to do more than glance at this title yet, for reasons that will become apparent over the next few days, but Mitford’s life sounds fascinating—I’m looking forward to eventually learning more.

I wanted to write a biography about someone who managed to hold on to the dreams of her youth. This elusive art was exactly what Jessica Mitford, as writer and provacateuse, triumphantly practiced all her long and adventurous life.

When I first read Mitford’s memoir Hons and Rebels, I was charmed by her rebellious and funny voice, and delighted to discover that she had left home at seventeen and set off to change the world on a utopian model. My escape at the same age was considerably less dramatic and I was fortunate to find a home in a counterculture that supported my initial wanderings and exercises in journalism.

In the early 1980s, I found work as a part-time librarian at the same San Francisco College of Mortuary Science that Mitford had eviscerated in The American Way of Death (grateful for a job that demanded no credentials). Four mornings a week, I would sit at a gigantic oak desk, inhaling formaldehyde and the must of unopened books, as I revised the plays I’d begun to write. I would filch announcements off the bulletin boards for weekend workshops in “head reconstruction,†and “grief counseling Bar-B-Ques,†and stash these away. Nobody would visit my library for weeks on end, except one young mortician-in-training who desultorily flipped through some books, then finally asked me out. He thought I might enjoy a tour of the building and I did. I saw the classrooms, laboratories, embalming rooms, and in the back yard what looked like twenty plastic gasoline cans full of blood. Once as I was snooping on my own, amid the back issues of “Mortuary Management†and “Casket and Sunnyside,†I found a file folder marked “Jessica Mitford.” I wish I could tell you there were explosive secret documents inside but it was empty. I always thought she’d get a kick out that, but I never met her—that is until I started to research this book.

8 November 2011 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.