Leslie Brody & The Inspiration of Jessica Mitford

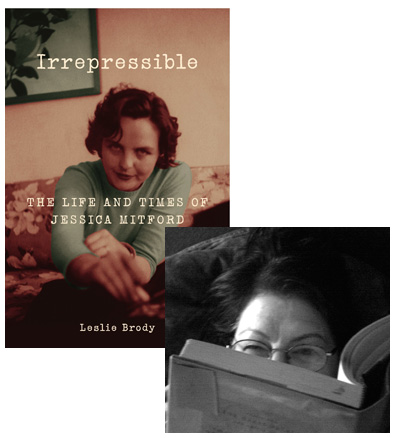

You know, we haven’t had a biographer drop by Beatrice in a while, so I’m delighted to share this essay from Leslie Brody about what led her to write Irrepressible: The Life and Times of Jessica Mitford and the inspiration she drew from her subject. I confess I haven’t had a chance to do more than glance at this title yet, for reasons that will become apparent over the next few days, but Mitford’s life sounds fascinating—I’m looking forward to eventually learning more.

I wanted to write a biography about someone who managed to hold on to the dreams of her youth. This elusive art was exactly what Jessica Mitford, as writer and provacateuse, triumphantly practiced all her long and adventurous life.

When I first read Mitford’s memoir Hons and Rebels, I was charmed by her rebellious and funny voice, and delighted to discover that she had left home at seventeen and set off to change the world on a utopian model. My escape at the same age was considerably less dramatic and I was fortunate to find a home in a counterculture that supported my initial wanderings and exercises in journalism.

In the early 1980s, I found work as a part-time librarian at the same San Francisco College of Mortuary Science that Mitford had eviscerated in The American Way of Death (grateful for a job that demanded no credentials). Four mornings a week, I would sit at a gigantic oak desk, inhaling formaldehyde and the must of unopened books, as I revised the plays I’d begun to write. I would filch announcements off the bulletin boards for weekend workshops in “head reconstruction,†and “grief counseling Bar-B-Ques,†and stash these away. Nobody would visit my library for weeks on end, except one young mortician-in-training who desultorily flipped through some books, then finally asked me out. He thought I might enjoy a tour of the building and I did. I saw the classrooms, laboratories, embalming rooms, and in the back yard what looked like twenty plastic gasoline cans full of blood. Once as I was snooping on my own, amid the back issues of “Mortuary Management†and “Casket and Sunnyside,†I found a file folder marked “Jessica Mitford.” I wish I could tell you there were explosive secret documents inside but it was empty. I always thought she’d get a kick out that, but I never met her—that is until I started to research this book.

I learned that when it came to staring down an authority figure, Mitford was implacable, always dressed and polished. Whatever her inward churning, projecting a fearless appearance was a cultivated habit reaching back to the 1930s; when as the daughter of English aristocrats she’d repudiated their wealth and privilege, and run away to the Spanish Civil War with Winston Churchill’s nephew.

Mitford felt capable of anything and had confidence that she would prevail as long as she kept all her wits about her. She was often so unexpectedly funny she could lull or distract her quarry, like a jaguar. Most people didn’t notice that she’d gone for their jugular until they were gasping. She counted on her opponents being slower, and they almost always were, particularly those puffed up with power. For example, when she ran away from home, Anthony Eden the British foreign minister sent a warship to Spain to retrieve her. She didn’t wish to go home, she wanted to stay and fight fascism. One has only to think of turning a battleship around to get the picture.

Her career as a journalist began in the mid-1950s with a series of reports documenting her work as a civil rights activist in Mississippi. Mitford viewed racial segregation as another version of the fascism she’d opposed since she’d run away from home. After her immigration and settling in Oakland, California, she would find her métier in muckraking: exposing dubious practices in (among other things) the America funeral industry and prison system, correspondence school swindles, and fraudulent medical rackets.

“What I enjoy is the chase,†she said to one interviewer. “One muckrakes because it is fun,†she told another. She was by all reports a scrupulous fact gatherer with a code of ethics that emphasized “being fair and never distorting the facts.†Objectivity, on the other hand, always seemed a bit of a fluid concept. “I really don’t understand what objectivity means,†she’d admit. “I’m not terribly in favor of balance, I may be unbalanced myself.†She hadn’t much use for psychology but she would never underestimate the recipe of idealism, indignation and stamina. Such a fuel might overcome any obstacle. The trick, she’d tell her journalism students, is “just keep going until you get into the mechanism of the brain.â€

“She just felt she could do anything,†her assistant Catherine Edwards said, recalling the time Mitford was on her book tour for The American Way of Birth. She was in her late sixties and hobbled slightly, the result of a recent leg injury. They’d arrived at the station late. And when it looked like she might miss her train, Mitford—dressed in a long red cape—raised her walking stick high in sight of the conductor at the controls of his locomotive and commanded “Stop!â€

He did.

8 November 2011 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.