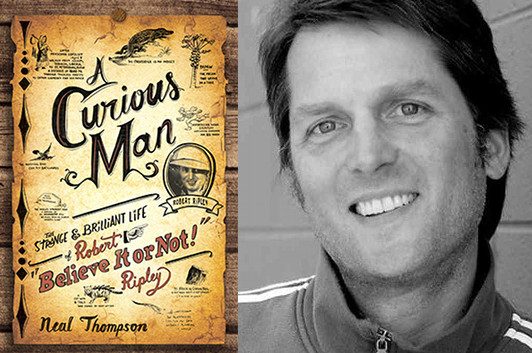

Neal Thompson’s Ultimate Underdog Tale

photo: NealThompson.com

A Curious Man is the story of Robert Ripley, a cartoonist who became not just one of 20th-century America’s most successful media personalities, but actually shaped the nation’s popular speech—the Ripley who made “Believe It or Not!” a catch phrase. Neal Thompson tells us what led him to tell that story—and he’s got a detail of special relevance to this blog. “Beatrice was the name of Ripley’s wife, a beautiful Zeigfeld Follies dancer,” he reports. “Their volatile three-year marriage ended in divorce, but they stayed in touch the rest of their lives. Hoping that’ll be the same for me and you, Beatrice.”

I’ve always been fascinated by the origins of books—mine and others, and especially nonfiction. Over the years, I’ve spend a lot of time meeting with and interviewing other authors, and I always have to ask: Why devote two, three, five years of your life to this person? Why thisstory? Now I get to challenge myself with the same question: Why invest half a decade in researching and writing the life of Robert Ripley?

For me, committing a chunk of my life to a particular life story requires two qualities: a come-from-behind arc, and an aspiration toward excellence. In most cases, my ideas ferment for years before they feel ready to be uncorked. In the case of Ripley, though, it was uncorked love at first site.

Unlike my previous books, I can pinpoint the exact day this story became my inspiration-slash-obsession: August 24, 2007. That’s the day I read a New York Times article about a Ripley’s Believe It or Not museum opening in Times Square. The story included a brief description of Ripley the man, and something clicked. “Oh yeah,” I thought. “There was a real guy named Ripley. I wonder what he was like?” Six years later, I’m still wondering, which is a good sign—I never got bored of this guy.

13 May 2013 | guest authors |

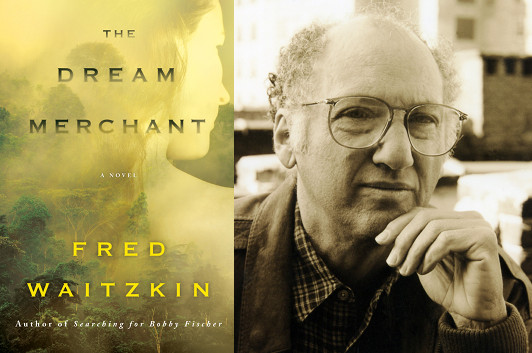

Fred Waitzkin Circles Back to Fiction

photo: Bonnie Waitzkin

Fred Waitzkin’s debut novel, The Dream Merchant, “tells the story of a gifted salesman who can sell anything to anyone,” as he described it when he sent his guest essay along. I say “debut novel,” but Waitzkin’s been writing for years; even if you didn’t read his memoir about raising a chess prodigy, Searching for Bobby Fischer, you might’ve seen the movie—and that’s just one of his books. So why, after all this time, a novel? “It’s a layered question,” he wrote, “and for a semi-coherent answer I should start at the beginning.” (Afterwards, if you want to learn more about Waitzkin’s writing process, he spoke at length to Scientific American blogger Scott Barry Kaufman.)

When I was a 13-year-old boy growing up on Long Island, I dreamed of being a salesman like my dad. I worshipped him and wanted to follow in his footsteps selling fluorescent lighting fixtures for new office buildings. He was a great salesman—he landed a lot of big orders, and like my protagonist, he was not restrained by ethics or fear of hell. And I loved his chutzpah. I learned from Abe Waitzkin the language and ecstasy of the big deal, and ultimately I learned from him the tragedy of a salesman.

My mother, an abstract painter, hated the idea of her son being a salesman. She was always reading me poems and stories. When I was 12 or 13, she gave me Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea. By then I was already an ardent fisherman and Hemingway’s tale of heroic loss and longing written in short rhythmic sentences burrowed itself into my being. On the pages of my earliest short stories Mother would edit my prose with passionate (India ink) suggestions that looked like de Kooning abstractions. Mother would introduce lush metaphors that I had never imagined were in this world. Also, when I was a teenager, she introduced me to jazz and took me into Manhattan for drumming lessons. To this day I still pound out rhythms on the skins. But more to the point, I’ve refined the Afro-Cuban rhythms of my youth, and they are all through my prose. I write tapping my foot.

My parents disliked each other for as far back as I can remember. They were divorced when I was 16, but this dichotomy between my dad who was a meat and potatoes guy, brilliant but darkly pragmatic, and my mother, who thrived in fantasy and was dedicated to art, created a polarity that has guided my aesthetic life to this day.

21 April 2013 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.