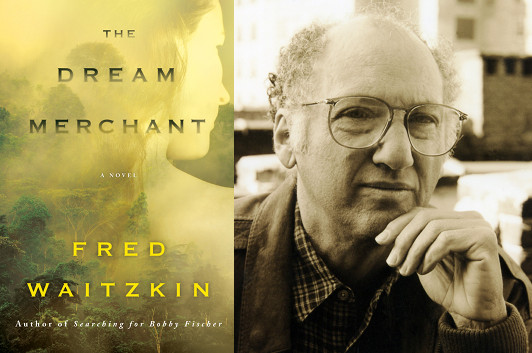

Fred Waitzkin Circles Back to Fiction

photo: Bonnie Waitzkin

Fred Waitzkin’s debut novel, The Dream Merchant, “tells the story of a gifted salesman who can sell anything to anyone,” as he described it when he sent his guest essay along. I say “debut novel,” but Waitzkin’s been writing for years; even if you didn’t read his memoir about raising a chess prodigy, Searching for Bobby Fischer, you might’ve seen the movie—and that’s just one of his books. So why, after all this time, a novel? “It’s a layered question,” he wrote, “and for a semi-coherent answer I should start at the beginning.” (Afterwards, if you want to learn more about Waitzkin’s writing process, he spoke at length to Scientific American blogger Scott Barry Kaufman.)

When I was a 13-year-old boy growing up on Long Island, I dreamed of being a salesman like my dad. I worshipped him and wanted to follow in his footsteps selling fluorescent lighting fixtures for new office buildings. He was a great salesman—he landed a lot of big orders, and like my protagonist, he was not restrained by ethics or fear of hell. And I loved his chutzpah. I learned from Abe Waitzkin the language and ecstasy of the big deal, and ultimately I learned from him the tragedy of a salesman.

My mother, an abstract painter, hated the idea of her son being a salesman. She was always reading me poems and stories. When I was 12 or 13, she gave me Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea. By then I was already an ardent fisherman and Hemingway’s tale of heroic loss and longing written in short rhythmic sentences burrowed itself into my being. On the pages of my earliest short stories Mother would edit my prose with passionate (India ink) suggestions that looked like de Kooning abstractions. Mother would introduce lush metaphors that I had never imagined were in this world. Also, when I was a teenager, she introduced me to jazz and took me into Manhattan for drumming lessons. To this day I still pound out rhythms on the skins. But more to the point, I’ve refined the Afro-Cuban rhythms of my youth, and they are all through my prose. I write tapping my foot.

My parents disliked each other for as far back as I can remember. They were divorced when I was 16, but this dichotomy between my dad who was a meat and potatoes guy, brilliant but darkly pragmatic, and my mother, who thrived in fantasy and was dedicated to art, created a polarity that has guided my aesthetic life to this day.

In my twenties, I spent years working on short fiction and trying to write novels. Back then I believed that for a writer, the novel was the heavyweight champion of literature. I didn’t take journalism seriously. I thought that journalists were hacks. But I struggled mightily in my early attempts to write fiction. It was a gloomy time in my life and my stories were dark, like my mother’s paintings, and not much happened in them. I struggled to get the words out and very few of my stories were published.

In my thirties, I started writing feature journalism for many of the big magazines: Esquire, New York, The New York Times Magazine. All of a sudden I had a mandate to write about real events, real people that did exciting things in the world. I found it liberating to move away from my angst, although when people asked what I was doing I half-slurred the word “journalist.” In this new field I actually earned money from writing. But I applied lessons that I had learned as a short story writer. Even though it was non-fiction, I wanted my stories to have a creative arc. I always wrote in the first person, which was somewhat unusual back then. I put my point of view right in, used irony, hyperbole, slang, whatever felt right, and for whatever reason, my editors often put up with it.

While working for the magazines I learned how to research a story. I learned to get at the core of a plot. But, most importantly, I was learning the importance of “story” in stories and how to write them in lean affecting prose. In a way, I suppose you could say I was learning to “sell” a story—my dad’s side of my writing life. Though it might sound crass, a great novelist is by definition a cracker-jack salesman—he wants his reader to buy what he is selling. What I didn’t understand in those years was that journalism is great training ground for a novelist.

During and following my journalism years, I wrote three memoirs, including Searching for Bobby Fischer. Each of these books required research and the management of a great deal of “story.” And the last of them, The Last Marlin, took liberties in both style and structure, as if it were a novel—in fact I was tempted to call it a novel. You see, my movement from non-fiction to fiction was not abrupt at all; it was something I was learning how to do all the while. I had wanted to write a novel as a young man, but I wasn’t ready.

When I began The Dream Merchant 12 years ago, many of the basics were already in my core. Like my dad, my protagonist is a super-salesman who crossed lines to close deals. Unlike Abe Waitzkin, who was sickly for his entire life, Jim is a physical powerhouse. He is a lusty man who needs beautiful women for energy and inspiration as well as sex. He is charismatic and charming but also unstoppable in business—a killer.

What would happen to such a man when doors suddenly begin closing in his face? What would he do when everything he’d built, a family and business empire, is suddenly taken from him? What would he be willing to do get it back and more? And how would the most radical and violent change of life imaginable change his character? Those were some questions I wanted to explore in my novel.

In 1984, I read an article in Time describing illegal gold mining in the Brazilian Amazon. Chiseled into the deep jungle there were camps called garimpos—and more of them were cropping up all the time. They were in fact, tiny lawless kingdoms cut off from civilization by impenetrable terrain, marauding bandits looking to steal gold, and vicious jaguars.

Virtually the only way out of these enclaves was by small plane. Each of the camps had a landing strip and a small barracks for a militia of gunmen who were employed to defend the gold operation from bandits. There was also a dining hall and a brothel with beautiful young working girls. The mining itself was done by garimpierros, who dug in mud pits around the camp searching for nuggets and gold dust. They slept at night beneath the trees and some were attacked and eaten by jaguars.

The men did this work in the hope of bringing a fortune back to their families in the city. But this rarely happened. At the end of a month of filthy, exhausting work a miner would wander into the garimpo lured by the sounds of romantic music crooning into the rainforest broadcast from big speakers. He would feel entranced by the music, the smell of good food but most of all by the beauty of the young women. He would spend all of his gold on one night of desire and wander back into the jungle the following morning to begin digging anew. It was a Sisyphean enterprise and the only ones who made substantial money were the owner of the garimpo and the working girls.

At some level, I percolated about the Amazon for years while I was writing my three memoirs. Eventually I travelled there with my son Josh. We spent nearly a month in the jungle south of Manaus, sleeping in hammocks beneath the trees, or hardly sleeping for worry about hunting jaguars and snakes that might crawl into our hammocks. We swam in the rivers even with knowledge of piranhas and a tiny fish called a candiru that can swim up a man’s urethra and become lodged there with spiked fins. We visited abandoned gold mining camps and witnessed the rare beauty of the rainforest—the utter intoxication of the place.

When I began writing The Dream Merchant, I was aiming to put Jim into the Amazon as the leader of an illegal mining camp. This was my home run idea—to turn Willy Loman loose in Kurtz’s world. I wanted to give my Jim a new and much darker palette and see where it would lead him and me. What would happen to this engaging charismatic selling man in a world where instant wealth, violence, and greed were the predominant language? How would this world change him? Could he survive it? Could he return to the prior life and continue as if he’d never lived in the jungle oblivious to mores and morality?

But even in the 1980s, while I was still writing feature magazine journalism and working on Searching for Bobby Fischer, I was already musing about the idea of a salesman attempting to refashion himself in the jungle—I was preparing myself to write The Dream Merchant.

21 April 2013 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.