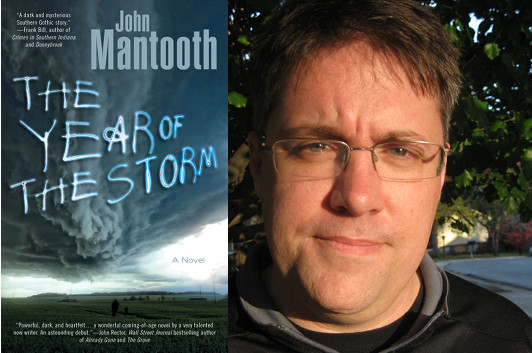

John Mantooth: Storms as Metaphors & Non-Metaphors

photo: courtesy John Mantooth

Earlier this year, I was asked to review Nathaniel Rich’s Odds Against Tomorrow; not knowing much about the story going in, I was caught off guard by the arrival of a megastorm with strong echoes of Hurricane Sandy, which was still lodged in the foreground of my memory. I had a similar experience with The Year of the Storm, the debut novel from John Mantooth, which I began reading in May, shortly before the tornadoes that went through Oklahoma. When the opportunity to have Mantooth write a guest essay for Beatrice presented itself, I wondered if he might be interested in discussing the power of stories about storms—he took my barely-formed idea and came up with a very effective statement about the potential resonance between fiction and our real-life experiences.

Anytime you write fiction, you run the risk of trivializing another person’s experience. Write about war and the veteran who swallowed the war whole when he was 21 and will die with that same war lodged in his throat, shakes his head, mutters in a disdainful voice, and walks away angry from your book because war just can’t be fiction. Not to him. Write about murder, and someone will read your book whose life has been touched by that act, and she will be turned off, will seek to read other kinds of books, the ones whose storylines don’t hit so close to home. It doesn’t matter how well you write about a topic, someone will always be hurt or turned off or angry. And that’s okay. Fiction must make some readers walk away or it’s probably not worth writing.

My first novel is set in Alabama, and I’ve lost count of how many twisters blow through the woods behind the narrator’s rural home. The book uses these tornadoes as a metaphor of transformation. Storms change things, they pick up the landscape and spin it around, dropping it back in unrecognizable pieces. The storm is a metaphor for growing up, for waking up and finding that the world is actually quite unrecognizable, that the very place you spent your childhood playing is really another place. It’s a book I’m proud of, and a metaphor that I think works.

21 July 2013 | guest authors |

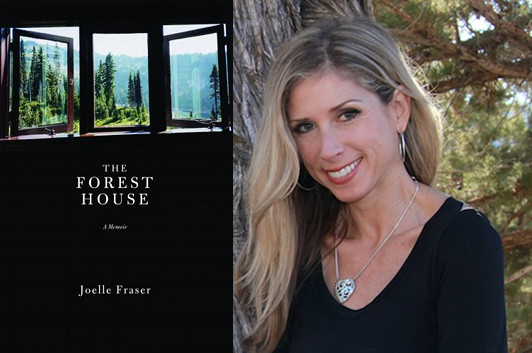

Joelle Fraser & the Return to Memoir

photo: JoelleFraser.com

In The Forest House, Joelle Fraser writes about life after the breakup of her marriage, when she moved to a remote town in California because it was as far as she could get away while still being close enough to make joint custody of her son workable. It’s the second time that Fraser’s put her life under the literary microscope, and in this essay she discusses what it’s like to re-subject herself to her own scrutiny—and, ultimately, of course, the scrutiny of others—and why, in the long run, she couldn’t stay away.

After my memoir, The Territory of Men, was published by Random House in 2002, I swore I’d never write another. Writing that book—a sprawling coming of age chronicle of my childhood in the wild California of the 1960s and ’70s and its effects on my adult life—nearly killed me.

Naively, when I turned in the final draft, I thought I was done with the hard part. I wasn’t prepared for the surreal pendulum effect of the memoir: after years of solitary, grueling self-reflection—you’re then hauled out into the public eye for months of astonishing exposure.

That’s the difference with memoir—sure, the fiction writer has the private/public dichotomy as well, but the memoir writer herself is just as much on display as her book. And so I discovered—as did my family—that reviewers often focus on the life rather than the writing of the life. (For instance, one well-known critic described my multi-married parents as “cancer cells uniting and dividing.”)

There’s really no way to prepare for the judgment—both good and bad—from the world. Writing can be hypnotic, can’t it? While bent to the page you can forget that most people don’t write books—especially not in the genre of memoir, which for the average person is akin to flashing yourself on Main Street.

Another uncomfortable discovery: at readings, I found that memoir writers tend to attract the lost and the needy, who sometimes see you more as a therapist than an artist.

Why would I put myself—and my family—through all that again?

20 May 2013 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.