John Mantooth: Storms as Metaphors & Non-Metaphors

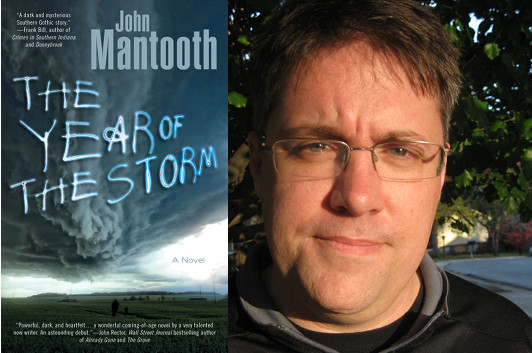

photo: courtesy John Mantooth

Earlier this year, I was asked to review Nathaniel Rich’s Odds Against Tomorrow; not knowing much about the story going in, I was caught off guard by the arrival of a megastorm with strong echoes of Hurricane Sandy, which was still lodged in the foreground of my memory. I had a similar experience with The Year of the Storm, the debut novel from John Mantooth, which I began reading in May, shortly before the tornadoes that went through Oklahoma. When the opportunity to have Mantooth write a guest essay for Beatrice presented itself, I wondered if he might be interested in discussing the power of stories about storms—he took my barely-formed idea and came up with a very effective statement about the potential resonance between fiction and our real-life experiences.

Anytime you write fiction, you run the risk of trivializing another person’s experience. Write about war and the veteran who swallowed the war whole when he was 21 and will die with that same war lodged in his throat, shakes his head, mutters in a disdainful voice, and walks away angry from your book because war just can’t be fiction. Not to him. Write about murder, and someone will read your book whose life has been touched by that act, and she will be turned off, will seek to read other kinds of books, the ones whose storylines don’t hit so close to home. It doesn’t matter how well you write about a topic, someone will always be hurt or turned off or angry. And that’s okay. Fiction must make some readers walk away or it’s probably not worth writing.

My first novel is set in Alabama, and I’ve lost count of how many twisters blow through the woods behind the narrator’s rural home. The book uses these tornadoes as a metaphor of transformation. Storms change things, they pick up the landscape and spin it around, dropping it back in unrecognizable pieces. The storm is a metaphor for growing up, for waking up and finding that the world is actually quite unrecognizable, that the very place you spent your childhood playing is really another place. It’s a book I’m proud of, and a metaphor that I think works.

But in real life, a storm is not a metaphor. It’s a soul-crushing jab to the solar plexus from nature’s tightly balled fist. Except hitting the solar plexus is completely random. Next time, nature might whiff entirely, and she won’t give a damn. She’s indifferent, and indifference is the cruelest emotion there is. Attaching significance to where and when she’ll strike is an exercise of backward religion or fiction.

The tornadoes that came through Tuscaloosa in 2011 were a knife through this state. They left a gaping wound that has only just begun to scab over. I wrote about storms, but not those storms. Mine were guided by an author’s hand, and they largely confined themselves to rural parts of the state, where they spun out their fury on trees and cotton fields. The ones in Tuscaloosa cut a swath through the town a mile wide. An entire street was savaged, destroyed, blown the hell away. Forty-three people were killed. There’s no metaphor here. Just cold, hard, indifferent facts. I wish they were fiction, but they’re not.

I’m sure some people—especially those in Alabama and other areas who have been affected by tornadoes—might walk away from my novel, and I could never blame them. I won’t pretend to understand their grief, their wounds, their anger and despair. I’ve been lucky. I’ve grown up in Alabama. I’ve crouched in hallways, hidden under crawlspaces, and been emotionally stricken by storms for as long as I can remember, but I’ve never had my life transformed by a storm that swept away not only landscapes, but lives. So I recognize that it is with the privilege and luxury of the safe and high ground that I write about them.

We need metaphorical storms for the same reason we need all metaphors: to understand the world around us. Without metaphor, without fiction, the storms that blew through Tuscaloosa in 2011 are even more horrible. Not because they hurt the people who were in the path any worse, but because they strike free from context, out of a bleak and cold sky, one that offers no judgment or benevolence. Fiction allows us to shape that sky, to shape that storm, and to sometimes even shape tragedy into something meaningful because, metaphors—stories—are all we have to make sense of the world. It’s all we’ve ever had. But I think that’s enough.

21 July 2013 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.