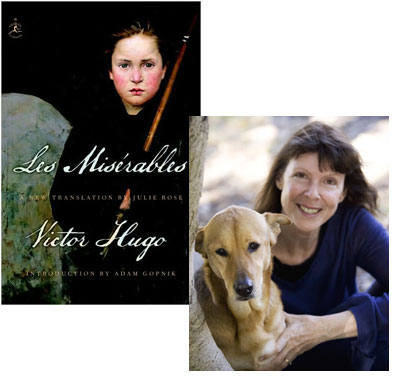

What Julie Rose Adds to Victor Hugo

When I began conceiving of the “In Translation” series of essays last year, one of the first translators I wanted to invite was Julie Rose, as her mammoth new English-language version of Les Misérables had just been released. I finally took the opportunity earlier this year, when I learned that she was among the finalists for the French-American Foundation’s annual translation prize; we began corresponding, and eventually a gap came up in her schedule (as she notes early on, she’s kept very busy translating modern French literature!) when she was able to share her thoughts on tackling Victor Hugo’s most famous novel. The appearance of this essay coincides with Rose’s first visit to the United States; in fact, if you follow Beatrice on Facebook, early next week you’ll get the inside scoop on a small gathering we’ll be having in New York City. I’m looking forward to meeting her in person, and I hope I’ll see some of you there!

I have four new translations out there on the shelves at the moment, all published in the last fourteen months.

The most mammoth of these is Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables, published by Random House (New York) and Vintage (London) in hardback last year—now out in paperback. At the opposite end of the spectrum is André Gorz’s slim but relentless letter to his wife of 58 years, Letter to D., published by HarperCollins (Australia) last year and by Polity Press in the US and UK recently; and French-born, Sydney-based Catherine Rey’s Stepping Out, an autobiographical portrait of the artist as a young—and not so young—woman, published by Giramondo (Australia) late last year.

The fourth book, Film World, is a collection of interviews with celebrated filmmakers recorded over decades by French film critic Michel Ciment. That was an interesting project, since Ciment had recorded a number of the interviews originally in English, which he speaks, before translating them into French. I then had to translate them back into English, without, in most cases, anything to go by, since the tapes had been trashed and most had never been published in English before. It was fun ‘playing’ 25 wildly idiosyncratic cinematic geniuses.

There would normally be a splendidly hybrid book by cultural critic Paul Virilio, as well. He turns out one a year and I’m never too far behind; though not yet out, University of Disaster is coming soon. And I’ve just finished a draft of an intricate theoretical work by Jacques Rancière, Politics of Literature. I myself am dazzled by the scope of this list of fabulous books. Hugo, Gorz, Rey, Ciment, Virilio, Rancière: writerly biodiversity in action.

Such a list presents vast differences in style, emotional register and temperament, context and resonance and intellectual tone—all those qualities that go to make the thing we call ‘voice’. Some people talk about texture, flavour, music, taste, colour. These are all sensory metaphors for the same thing. I prefer to call it ‘voice’ to suggest the theatricality not only of the embodiment of personality in writing in the first place, but the whole performance of re-embodiment that the process of translation entails. Translation is rewriting—as someone you imagine the writer to be.

A writer’s ‘voice’ in this sense is as unique as the thing produced by their vocal chords, no matter how codified shared language and the rules of writing might be. It is ‘voice’ that a translator worth her salt is always trying to mimic.

Translation as an art is an art of listening that means getting into ‘character’ and staying there, convincingly, from start to finish. In so doing, of course, you produce your very own distinct voice, with its very own timbres and energies. Which is one reason why re-translating is a potentially endless field. The original text stands immutable, but its potential translations are potentially infinite.

For me, there’s a golden rule here which is that, the more distinct that ‘second’ voice—the voice that you the reader, who needs the translation, receives—the more intensely and successfully I, who don’t need the translation, have managed to ‘get’ the original.

The ‘successful’ translation is the one where I, the translator, am completely invisible. A translator’s glory lies in their own disappearance. Nothing could be more satisfying. For others. Of course, every word is mine as much as his or hers. It is a double act, after all.

1 September 2009 | in translation |

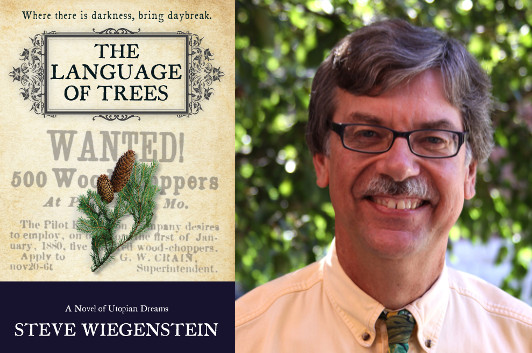

Steve Wiegenstein: Utopia & Me

photo: Kaci Smart

The Language of Trees is the third in Steve Wiegenstein‘s series of novel about Daybreak, a fictional utopian community in 19th-century Missouri. I’d not come across the previous two, Slant of Light and This Old World, but it doesn’t matter; you’ll be able to dive into the world Wiegenstein’s created and sort out the relationships between the various characters easily enough—and chances are you’ll get hooked by the story of how the community deals with the arrival of a lumber and mining company looking to acquire the natural resources within Daybreak’s boundaries and the surrounding landscape… which makes this a very timely story indeed. (And, he says, there’s already a fourth novel in the works, which will bring Daybreak into the twentieth century.) Here, he talks a bit about some of the historical inspirations for these novels.

In 2006, I awoke one morning with what I thought was a great idea for a novel.

Before I go any further, let me give you some background about myself. I am a longtime teacher at the college level, and over the years have been fascinated by the utopian movements of the 19th century. There were lots of these communities across the United States in the 1830s and 1840s; the Shakers, Brook Farm, New Harmony, Oneida, are just a few of the most familiar names. I also have a background in creative writing, although in 2006 I had not pursued that interest for quite a while.

The idea I woke up with that April morning was to combine these two interests and create a fictional utopian community in the Missouri Ozarks, the area where I grew up, in the years before and during the Civil War. I figured that the clash of a group of idealists with the troubles of the times would provide lots of opportunity for drama. So I started to write, and for the past eleven years I have rarely gone more than two days in a row without spending time working on the books that have grown out of that initial idea.

12 December 2017 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.