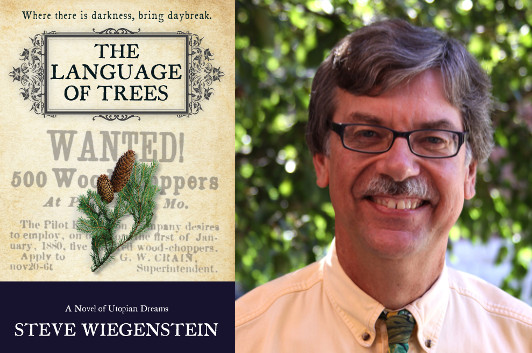

Steve Wiegenstein: Utopia & Me

photo: Kaci Smart

The Language of Trees is the third in Steve Wiegenstein‘s series of novel about Daybreak, a fictional utopian community in 19th-century Missouri. I’d not come across the previous two, Slant of Light and This Old World, but it doesn’t matter; you’ll be able to dive into the world Wiegenstein’s created and sort out the relationships between the various characters easily enough—and chances are you’ll get hooked by the story of how the community deals with the arrival of a lumber and mining company looking to acquire the natural resources within Daybreak’s boundaries and the surrounding landscape… which makes this a very timely story indeed. (And, he says, there’s already a fourth novel in the works, which will bring Daybreak into the twentieth century.) Here, he talks a bit about some of the historical inspirations for these novels.

In 2006, I awoke one morning with what I thought was a great idea for a novel.

Before I go any further, let me give you some background about myself. I am a longtime teacher at the college level, and over the years have been fascinated by the utopian movements of the 19th century. There were lots of these communities across the United States in the 1830s and 1840s; the Shakers, Brook Farm, New Harmony, Oneida, are just a few of the most familiar names. I also have a background in creative writing, although in 2006 I had not pursued that interest for quite a while.

The idea I woke up with that April morning was to combine these two interests and create a fictional utopian community in the Missouri Ozarks, the area where I grew up, in the years before and during the Civil War. I figured that the clash of a group of idealists with the troubles of the times would provide lots of opportunity for drama. So I started to write, and for the past eleven years I have rarely gone more than two days in a row without spending time working on the books that have grown out of that initial idea.

The utopian impulse, in the abstract, is a reasonable response to the messiness and inherent unfairness of life. Everyone agrees to a set of principles that will govern their behavior, and from that point on, everyone gets treated equally. That’s the theory, anyway, but history is littered with examples of how that theory foundered on the rocks of human imperfection. The contrast between ideal and actual provides ready-made tension, which appealed to my instincts as a writer.

Viewing utopian communities entirely through the lens of “failure,” though, is a mistake. Success and failure on whose terms? The more I studied these communities, the more I came to respect and even admire their astonishing levels of commitment, the sacrifices members made to advance the community ideal, and their persistence in the face of hardship and external disapproval. The intensely human dramas of aspiration and love grew in importance, while the mere sociological curiosity faded.

The community that drew me the most was the Icarian community, which was composed mainly of French immigrants and lived in the Midwest. Their founder was a man named Etienne Cabet, a prominent socialist who served for a time in the Chamber of Deputies. His radical ideas got him into trouble, and while in exile, he read the work of Robert Owen and wrote a utopian novel, Voyage en Icarie, which gained him attention and a sizable following.

Scholars generally believe that Cabet wrote his novel as a work of social criticism intended to point out flaws in French society, but to the surprise of many, including Cabet himself, many of his followers took it as a blueprint for the establishment of an ideal society. In 1848, Cabet found himself at the head of a group of colonists sailing for New Orleans.

The rest is a story of optimism, disaster, and determination worthy of Victor Hugo. When the group arrived in New Orleans, they were met by the tattered remnants of their advance guard, which had been sent to secure land in Texas but returned with the news that the land they had bought was impossible to settle. Their initial dream thwarted, the colonists made a deal out of necessity to buy the recently abandoned town of Nauvoo, Illinois. They steamed upriver, losing members to cholera along the way, and settled among the ruins of the Mormon temple with Cabet as their president.

But after a few years, Cabet proved to be an unsuitable leader, impractical and autocratic, and the colonists voted him out of the presidency. The vote caused a split in the community; Cabet led a group to St. Louis, while the remaining members relocated to southwestern Iowa. The St. Louis group persisted after Cabet’s death until the coming of the Civil War broke them up for good.

The Iowa group, by contrast, prospered during the war as their land holdings and proximity to a rail line fostered a lucrative business raising beef for the Union Army. A fairly steady influx of new immigrants kept their numbers up, but these new French communists were more radical than the older generation, and the colony split up again in the 1870s, with “New Icaria” occupying part of the acreage and “Young Icaria” the other.

The final dissolution of the colony came in 1898, marking the end of a fifty-year experiment in communal living for the Icarians. Those who have read my first novel will recognize some elements of the Icarian story in my fictional Ozark utopia of Daybreak.

As a native of the Missouri Ozarks, I’ve always been steeped in the history and culture of that region. In popular literature, movies, and TV shows, the Ozarks tends to be portrayed as a hotbed of hillbillies, meth cookers, and throwbacks, but I know it as a much more complicated place. It’s a part of rural America, with all the culture and struggles of rural America, and it also has a distinctive history.

The Civil War history of Missouri is incredibly tangled and not well known; it was characterized by Federal occupation of significant towns and cities, with intermittent and savage guerrilla warfare throughout the rural parts of the state. Large-scale battles were few, but nearly everyone outside St. Louis lived in a constant condition of uncertainty as roving bands of fighters, some affiliated with one side or the other and some simply using the war as an excuse, traveled the countryside engaging in warfare on a brutal, person-to-person level.

Combining these elements—a utopian community, the distinctive landscape of the Ozarks, and the experience of Missouri in the Civil War—I couldn’t resist the opportunity to create a novel series that began in that era and is still under way.

12 December 2017 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.