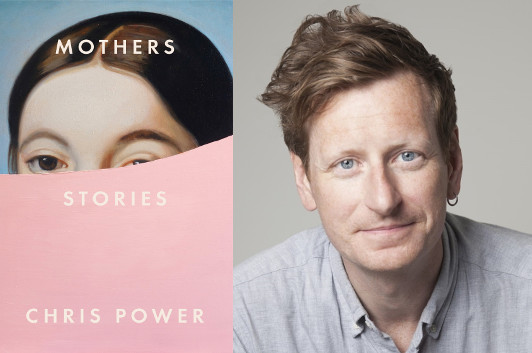

Chris Power: Discovering the Short Story

photo: Claudia Burlotti

A flailing standup comedian keeps his career alive by doing Rodney Dangerfield’s act, but you can just imagine how that makes him feel. A woman recalls growing up in an apartment complex in the 1970s, and the lie she told about one of her neighbors. A seemingly innocuous disagreement between two weekend vacationers over a hiking route turns out to have deep emotional undercurrents. These are some of the worlds of Chris Power’s debut collection, Mothers. One of the reasons I was interested in this collection is that, as he explains in the opening to this guest post, Power isn’t just a creator of short stories, he’s also a scholar of the genre—surely, I thought, he’d have some recommendations for the “Selling Shorts” series that would send me off not just in new directions, but new directions I hadn’t even known were on the map. You know what I mean: There’s a lot of writers we “know” we “should” read, and Power certainly mentions some of those, but there’s also the writers we had no idea we ought to be reading, and Power passes along some intriguing discoveries (for me, at least), too.

Since 2007 I’ve written a column called “A Brief Survey of the Short Story” for the Guardian. Each edition aims to provide an overview of the work of a single author whose work has some significance in the development of the short story form. It doesn’t operate to a strict timetable (it’s been nearly two years since the last edition, which I guess you could call a hiatus), but I’ve written 72 of the things so far, and I still have a list as long as your arm of writers I’d like to include in the future.

When I started the column I sketched a list of writers whose work I already knew pretty well: Chekhov, Kafka, Mavis Gallant, Raymond Carver, Grace Paley, Denis Johnson. But it wasn’t long before the column became my way of exploring the work of writers I knew a little, but not at any great depth. People like Clarice Lispector, Isaac Babel, Lydia Davis, JF Powers. And while this was going on, I was also starting to get reader recommendations of writers whom I’d never read anything by, and in some cases whose names I’d barely heard. All this led to a lot of discoveries of a kind that I think really helped me in terms of my own writing.

The short story covers a vast territory, from realist to fantastical, and I like to think I’m open to anything if the writing does its job and lashes my eyes to the page. My first encounter with the work of Dambudzo Marechera did just that. Marechera, who was from Zimbabwe and died of AIDS-related illness in 1987, aged just 35, described his work as a form of “literary shock treatment,” and you quickly see why. His chaotic stories, responses in part to the civil war that ravaged Marechera’s homeland for much of his life, are full of nightmarish transformations and moments of horror. Doris Lessing said reading him was “like overhearing a scream.” She’s right.

Varlam Shalamov describes another broken society in his stories, or perhaps it’s better to say a society geared towards breaking its citizens. He spent six years in the gold mines of Kolyma—one of the harshest zones of Stalin’s Gulag—and another nine as a paramedic in the penal camps. His stories are unremitting accounts of humans doing whatever they can—sometimes for each other and sometimes to each other—in order to stay alive in a supremely hostile environment.

At college I read Jean Rhys’s novel Wide Sargasso Sea, her incredible, feverish prequel to Jane Eyre, but I didn’t know her stories. When I began reading them I realized she belongs with the very best British story writers of the last hundred years. The work she produced in the late 1930s and early 1940s, much of which wasn’t published until decades later, often describes women attempting to navigate transactional sexual relationships, trying—and most often failing—to secure a degree of independence for themselves.

Rudyard Kipling can hardly count as obscure, but he wrote so many stories in so many different styles that it’s possible for some readers to know one Kipling and be completely ignorant about another. Despite the difficulties he presents—not least his associations with the British Empire and jingoism, neither of which sit well with me—I hugely admire his ability as a writer. I’ve read Plain Tales From the Hills, the Indian-set stories that made his name when he was just 23, since I was a teenager, but it was only much more recently that I explored his twentieth-century work.

In this latter half of his career his writing became denser, and the stories became stranger. “Mrs Bathurst,” from 1904, remains one of the strangest and most confounding stories that I’ve ever read. I’m not going to say more than that, but if you read it and think you’ve managed to figure out what the hell’s going on, please get in touch because I would love to know.

21 January 2019 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.