Virginia Pye: Black Tickets & Feminist Poets of Another Time

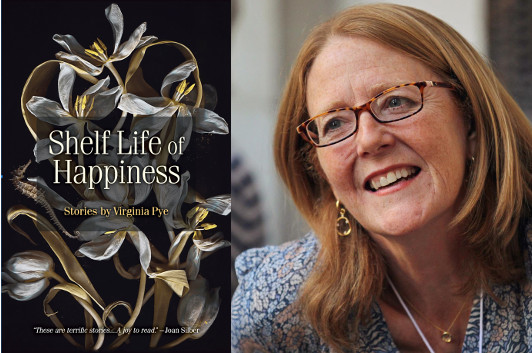

photo: Tennessee Photography

I met Virginia Pye at a book festival down in Richmond ages ago, so I was delighted to hear that she’s got a new short story collection, The Shelf Life of Happiness. In her stories, you’ll see how an elderly painter being courted by a rich young art collector and a teenage skateboarding enthusiast embarrassed to be driven to the skate park by his dad are fighting similar battles. You’ll also spend time with a man who’s accompanying his old friend from college, who’s now dying of AIDS, as he gets married in a remote town that’s little more than a few stores and a motel lining either side of the highway, and a woman who’s struggling to make sense of a brutal murder that stuns her small community. In this essay, Pye shares some thoughts about a story collection, and the poems that preceded it, that helped her clear a path to writing about characters struggling to figure out, let alone assert, their identities.

When I was twenty, Black Tickets, the story collection by Jayne Anne Phillips, with its hard-edged prose about hard-edged people, hit me hard. I’d read Hemingway’s short stories. Fitzgerald and Chekov, too. Isaac Babel and Isaac Bashevis Singer, and that one about the yellow wallpaper that everyone had to read. Unlike novels, short stories seemed the place to start for an aspiring young writer. Stories were like small sculptures, carefully shaped and refined, seemingly comprehensible with a single walk around.

But when I tried to write them, mine tended to sprawl into an unruly mess. My pages grew dense and overwritten as I attempted to say too much. Then I read Black Tickets and saw that when you used restraint, you created meaning in a more powerful way. If you kept it minimal, you could leave your reader aching for more, at least that was the hope. But it wasn’t just Phillips’ style of writing that I admired and wanted to emulate. Her stories hit home because they were about women and girls, not unlike me.

Even before Black Tickets became my anthem and guide, I had tucked poems by Anne Sexton, Denise Levertov, and Adrienne Rich into my backpack and carried them like talismans with me wherever I went. In high school, I memorized their lines and copied them out into notebooks for what reason I wasn’t sure. All I knew was that I loved those poems, loved the many lines that revealed the secret, passionate inner lives of women.

From Anne Sexton’s “For My Lover, Returning to His Wife”:

Climb her like a monument, step after step.

She is solid.

As for me, I am a watercolor.

I wash off.Denise Levertov”s “The Good Dream”:

Rejoicing

because we had met again

we rolled laughing

over and over upon the big bed.

The joy was

not in a narrow sense

erotic—not

narrow in any sense….It was the joy

Of two rivers

Meeting in the depths of the sea.And Adrienne Rich’s “Natural Resources”:

“The phantom of the man-who-would-understand,

the lost brother, the twin—

for him did we leave our mothers,

deny our sisters, over and over?”These women wrote about many subjects, often political, but what captured me most was the way they teased out the tangle of love that I both longed for and feared. Stoked by their fury and sorrow, and as importantly, by the precision of their words, I prepared myself for the battle for selfhood I sensed every woman had to endure.

Their feminist ideas resonated because they were expressed so potently through poetry. I was learning from them not just about life, but about the power of words and their careful doling out. I sensed that a killer line—one that resonated deeply, even though I might not fully understand it—was armor against a difficult world. The urgency of their language took my breath away and made me want to someday write something as forceful and real.

It was no wonder then that when Annie Dillard, my writing teacher in sophomore year at Wesleyan, praised a powerful collection by a young woman writer, I quickly tracked down a copy of Black Tickets. In Phillips’ pages I soon discovered the powerful combination of story telling and poetry that I had been searching for. Her sentences were as tough and clean as Raymond Carver’s, whose work Dillard had also recommended, but Phillips wrote about girls and young women in narratives that suggested lives far beyond the page. I felt a thrill of recognition in these tales that unmasked the struggle of ordinary female lives.

Phillips’ “Home” felt like one I’d been trying to write for years without knowing it. The story lacked sentimentality and yet was full of nostalgia for a stolen childhood. It showed a grappling with growing up and a recognizable tension between a mother and daughter. She said so much by saying so little. The short, declarative sentences left room for the reader to fill in the blanks with emotion, in a way familiar to me from the poetry I had long admired.

Soon Levertov, Sexton, and Rich were replaced in my backpack by Black Tickets, which I then carried with me everywhere. When I sat down to write a short story for that first-ever fiction writing class with Dillard, I had my copy splayed open on the desk, as if I could somehow will Phillips’ smarts and style over to my pages.

In looking back, I feel grateful to these women writers for exposing female lives with such fierceness and brilliance. I’ve spent the years ever since trying my best to follow their example.

23 October 2018 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.