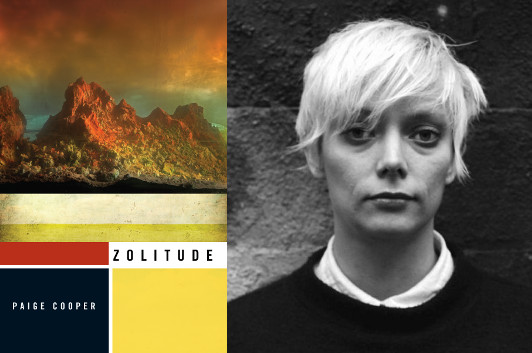

Paige Cooper on Peter Carey’s Fantastic

photo: Adam Michels

The short stories in Paige Cooper’s Zolitude are dark and uncanny, and it takes a while to get adjusted to her world. Even a story like Moriah, which starts off with a woman driving a bookmobile to a remote community of registered sex offenders—a premise that’s odd, to be sure, but still within the bounds of the plausible—may end up taking a sudden turn into fantasy, leaving you to sort out what’s just happened. In this guest essay, Paige talks about discovering another author with a flair for the fantastic, Australia’s Peter Carey. But this is no simple panegyric; Cooper’s nuanced appreciation of Carey’s short stories helps us see certain “gaps,” as she calls them, that we can learn to recognize (as both readers and writers) and face head on.

When we were nineteen my new friend said, “What about Peter Carey, though? Did you read the one where he goes ‘EVERY TIME WE FUCK A HORSE DIES’?” We knew each other from our undergraduate fiction workshop. She was the best writer at the table. This was because she was the best reader. We’d go for spring rolls and cokes at a Vietnamese place off-campus. I never mentioned the demolished copies of George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice & Fire in my dorm room. Maybe I alluded to the uncracked copy of War & Peace. Mostly I wrote down names she mentioned.

“Uh, no,” I said. I cared about fucking, I cared about horses, I liked capslock. I wrote PETER CAREY in my student agenda. A few weeks or months later I was at the discount bookstore downtown where everything was always remaindered or crap and Collected Stories was sitting on top of a bin of low-fat cookbooks. It became the first book of short fiction I’d ever purchased. Plausibly, it became the first contemporary short fiction I’d ever read (despite having already written two or three short stories in order to get into a creative writing program so that I could, presumably, write more.)

If you’ve read Carey, you’ve probably read Oscar and Lucinda, or The True History of the Kelly Gang, or maybe The Unusual Life of Tristan Smith, or one of the more recent ones. He’s got a lot. He’s won two Bookers. My favorite Carey novels overflow grossly, variously gaudy or bawdy, bloated with injustice. Each is giddy and cunning in its own invented or reinvented language. Carey’s short stories are not like that. While they’re as ambitious in premise as his novels, the language is arch, dry, minimal. The stories don’t build worlds, they tack up some scaffolding and walk away.

In the one where every time they fuck a horse dies (a.k.a. “Life & Death in the South Side Pavilion”), the narrator is not sure that his station is still referred to by the Company as the South Side Pavilion, or whether he should still refer to himself as a Shepherd 3rd Class. In a corner of the pavilion there is a bed, a gas cooker, a refrigerator and a television set. There is also a large pool. The rest of the pavilion is occupied by a herd of horses. A woman named Marie shows up sometimes to have sex with the narrator.

The narrator writes letters to unknown superiors, pleading to be relieved of his post because he can’t stop the horses from falling into the pool and drowning loudly and horribly. The narrator knows very little; his world is circumscribed into a bleakly-detailed futurelessness. Reading all this fifteen years ago, I was bewildered then annoyed then excited: the narrator’s constriction was my freedom. I’d never read anything with so many gaps for me to fill. The story forced me to be responsible for it.

Carey could write the fantastic so precisely that it became realism. Other stories that stuck with me from that book: “Conversations with Unicorns,” “A Windmill in the West,” and “The Journey of a Lifetime.” The cave-dwelling English-speaking unicorns living on the line between ignorance and innocence; the fence in the desert on the border of America and Australia; the minor bureaucrat and his fetish for luxury trains: these stories don’t eschew reality so much as opt for a larger one.

Carey was writing realities that could contain the fantastic, and allow it to act as the fantastic does: unpredictably, like emotion. Fabulous or surreal elements defamiliarize the world the same way falling in or out of love does. Reading him, I learned I didn’t have to abandon my imagination and start recording my domestic resentments in order to write literary fiction. (Remember I was nineteen, I liked false binaries.) However, I didn’t learn—not for years and not from these stories—that writing the fantastic doesn’t mean abdicating responsibility for the real.

The stories in the collection were first published in the 1970s, and re-reading these four in particular I see a little Saunders, a little Barthelme, a little Millhauser. I also see one demographic: straight white men clinging to what little social status is left to them, confused and often pathetic. Perhaps this is as it should be: Carey doesn’t appropriate experiences that aren’t his. The problem is that he doesn’t seem to be all that concerned with anyone else’s experience.

There are two female characters in the four stories I’ve been re-reading: Marie and an unnamed sex worker. The woman is professional. Marie is sharp and funny. Both are cannier than their narrating men. Neither does anything but speak a few lines and have sex. Meanwhile, class is central but race is never mentioned. Carey doesn’t even specify the color of the unicorns, because the default for unicorns is also white.

Carey is vigilant about power, class, hegemony, bureaucracy, and morality. However, my suspicion is that, in these stories at least, he cared about injustice only as it affected him. This authorial tightness of scope is a correlate of the narrators’ constricted knowledge. These are minimalist short stories: their ambitions are focused. But if a writer is capable of building a story out of gaps in knowledge, surely that writer can—and would be excited to—make use of gaps in empathy as well.

As a kid I was aware that I read to escape, and I was ashamed. Escapism, I was told, was the opposite of “honest work.” (By this my folks meant homework; though I was also neglecting human connection, which is harder work.) There is a risk, in writing dinosaurs or giant eagles or spaceship romance—all of which I have done, albeit using special literary sentences—that the fantasy-as-larger-reality becomes just a different reality. A straight reality, a white one. Able-bodied, cisgender. An easier reality, where questions of cultural theft, fetishization, the male gaze, white privilege, don’t exist if the author doesn’t want them to.

Part of the work of a fiction writer is necessarily to frame, which requires exclusion. Excluding what’s difficult becomes a kind of escapism that is, yes, legitimately shameful. Let me escape to a place where the only problems are the ones that affect me. You know. Horses, fucking, capslock.

Carey said he didn’t write his latest novel, A Long Way from Home, until now because he had felt it wasn’t his place, as a white Australian, to write about the country’s history of brutal racial violence, but eventually ignoring it became untenable. I can’t speak to his success, but I’d guess there are gaps in that novel. I don’t mean imperfection, which is a given. I mean gaps left open for empathy rather than fact. The process is often painful, the results inadequate. Erect the scaffolding, just don’t walk away. Attend to the gaps gratefully, because the story will make you responsible for it.

4 May 2018 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.