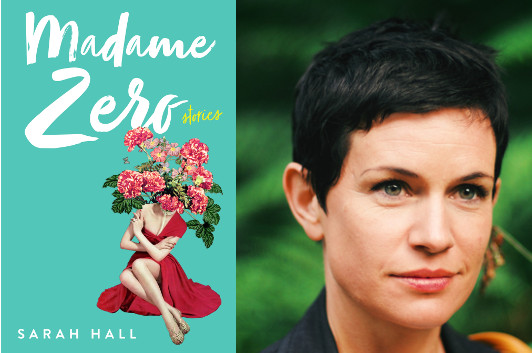

The Short Stories That Haunt Sarah Hall

photo: Richard Thwaites

I’ve been a fan of Sarah Hall for about a decade now; she’s even been a guest for a literary event I curated back in the day. So I was very excited to see her new short story collection, Madame Zero. From the outright fantasy of “Mrs. Fox” to the emotional turbulence bubbling under the clinical detachment of “Case Study 2” to the grim, twenty-minutes-into-the-future premise hanging over “Theatre 6,” these stories are staying with me, and I expect I’ll be thinking about them—and the other six stories, as I finish them in turn—for some time to come. In this guest post, Sarah talks about some stories that have stayed with her through the decades.

My earliest memories of short stories are from infant school—sitting on the blue carpet of the tiny library, aged six and utterly spellbound as the headmaster recounted by heart a series of Lake District folk tales. The Windermere Ferryman. The Hairy Toe. The Cappel (a large, flame-eyed, ghost dog): This was mind-twisting stuff in the late 1970’s, before you weren’t allowed to terrify small impressionable people, or suggest to them that at any moment life could be thrown out of kilter.

The power and atmosphere of those uncanny goings-on had a lasting effect. I look for the same primordial qualities in short fiction now—the sense of being haunted, literally, emotionally, or philosophically, the idea of human mutability, the world’s mutability. As a teenager, I remember reading “Hunters In The Snow” by Tobias Wolff and feeling a similar toe-curling dread, at the awful drama and the solipsism of the characters. I remember panicking internally, thinking, stop, stop, he’s going to die, while the events moved in opposition, regardless. That was my first understanding of the mental bifurcation short stories can create.

Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber And Other Stories also contained appealingly unsettling scenarios, sexual subversions, and the all-important animal motifs (I was a rural kid). They were a perfect continuation of those childhood tales, but with a thrilling new sensuality and linguistic verve that, as a young adult, blew my mind. I still love her work.

Later, I studied poetry and short stories on the creative writing program at St. Andrews University. The notion that short form was dependent on very careful construction and select materials, like a poem, was tantamount. On the course, I encountered Flannery O’ Connor, J.D. Salinger, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Edgar Allan Poe: an elite posse of experts, capable of beautiful and excruciating metaphysics. I also met a lot of American students and began to understand how respected the form is in the United States, how important a space in literary history it occupies, and how committed to its study and practice contemporary writers are.

Like poetry, short story apprenticeships can take time. For a long while, I couldn’t produce anything even approaching decent. I didn’t understand what was required—the fictive legerdemain necessary to compress and distill worlds and meaning into microcosm, calibrating component parts, alluding, omitting, creating that duality of surface story and undercurrent, dismounting normality. I didn’t know how to do it.

But I kept reading: Anton Chekhov, Nikolai Gogol, Katherine Mansfield, Richard Brautigan, Edna O’ Brien, Tessa Hadley, James Salter, George Saunders, Ali Smith, Jon McGregor. Exacting though the form is, it’s wonderfully accommodating of experiment, modernity, and adaptation. There are many more writers of the past I could cite, but I’m most excited by writers today whose work reflects the form’s finest traditions and its evolving possibilities, gender revolutions, science fictions, constructivism, and cutting-edge psychology.

I think Junot Diaz is one of the most daring and intelligent contemporary writers, unafraid of difficult cultural, political or behavioral terrain, and capable not only of producing brilliant individual pieces, but collating them in such a way as to create larger narrative, meta-story. This Is How You Lose Her is a phenomenal piece of work. To traverse the unforgiveable acts of the philandering serial narrator, Yunior, as he pathologically lies and cheats on women, is quite an experience for a reader. But the dehumanization and humanization processes of the characters involved is so finely expressed and examined, the damage is so purposeless while the narrator’s journey is so instructive, that by the last story the reader arrives at a very unexpected place—not redemption, exactly, but amnesty. Diaz is a writer who understands that the form is a remarkably stable item wherein incalculable destabilization might occur, human conflict, undoing, and restructuring. We are not what we are, but what we become.

Though they formed the basis of my earliest literary experience, with their calling cards of disquiet and otherness, and they still hold that essential resonance for me, short stories now seem more about companionability in a complex adult world. We are never immune from chaos and change. We never lose the ability to be stupefied. What I like best about short stories is that no artificial consolation or solution to our (problematic) existence is offered.

Instead, they challenge and question civility and regulation, they disrupt peace of mind, and they frequently remind us of our mortality. They deal forthrightly or subtly in the business of life’s insolvency and our transitional selves. Don’t get too comfortable sitting on that blue carpet, little girl, they suggest, because at any moment it might be pulled out from under you.

25 July 2017 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.