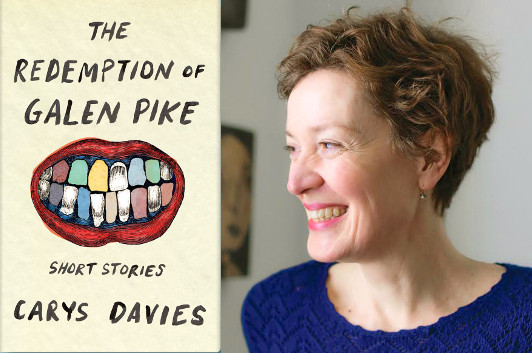

Carys Davies’ Brief Drama of the Soul

photo: Emily Atherton

The Redemption of Galen Pike, the Frank O’Connor International Short Story Award-winning collection from Carys Davies, takes readers to a lot of different places. The title story is set in a Colorado frontier town, where a virtuous Quaker woman comes each day to the cell where a murderer awaits his execution; other stories show readers a tense encounter between two isolated souls in the early days of Australian settlement, a lonely man who tells Queen Victoria the lurid story of his marriage’s end, a tragic scene played out in a Siberian hostel… Davies’ dramas are already stark, but they stand out even more aggressively in these settings, each one hitting home with unerring effect, even if—as will be the case with that title story—you think it’s veering into genre stereotype. In this guest post, Davies explains how she learned to identify the moments in her characters’ lives that make for great short stories.

People ask me all the time what it is I love about short stories, and why I write them.

It all began for me back in the mid-1990s. I was living in Chicago, working as a journalist. I had four small children, life was very busy, chaotic, and one day for a breather my husband and I took the kids to Powell’s bookshop where I came across a copy of Eudora Welty’s Collected Stories. It had a brown 1960s-ish cover and while the children ran amok in the aisles I sat down on the floor and read one of the stories: “Death of A Traveling Salesman.”

I’d never read anything like it. I was transported—by the tension, the mystery, the slow stealth with which Welty revealed things through the salesman’s unseeing eyes, and most of all by the way the story gathered towards the moment when the truth of the situation dawns upon the salesman. I loved how Welty captured the pain of his realization, so sharp and so fleeting—his understanding of everything that had never been and now never would be. The salesman’s revelation—this glimpse of something shattering and profound—took my breath away, and it’s fair to say the experience changed my life.

Unbelievable as it may sound, I hadn’t heard of Eudora Welty; I’m British, and I wasn’t, at the time, a big reader of short stories. I’d always read a lot, novels and non-fiction and poetry but not that many short stories. But I read this, and the other stories in the book, and they were a revelation. They felt like the truest thing I’d ever read.

I started looking for more short stories. I quit my job and in quick succession fell in love with Flannery O’Connor, Carson McCullers, Bernard Malamud, John Cheever; with TC Boyle, with Lorrie Moore, Tim Gautreaux, Amy Bloom and many more.

What I craved was the stories’ intensity, their capacity to take my breath away—to conjure an almost unbearable image or moment or feeling which burned itself into my mind and into my heart: the man and his two boys in Lawrence Sargent Hall’s “The Ledge” waiting, in the rising water, to die; John Cheever’s lonesome swimmer wandering through the gardens of his suburban neighbors until he reaches his own abandoned house; the nightmarish half-skinned steer stalking the old man through the wilds of Wyoming in one of Annie Proulx’s greatest stories; the moment when someone picks up the first stone in Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery”—or when Joyce’s Eveline pulls backs from the barrier and from her young man and from an entire future to stay home in Dublin. Oh I could go on and on! These moments or images were freighted with such extraordinary power and resonance they seemed to drop like stones straight into my heart, the ripples spreading outward as the reverberations and implications of the moment began to take hold.

Ben Marcus says something similar in his introduction to the marvelous New American Stories anthology Granta brought out a couple of years ago. “Once they take hold,” he says, “you couldn’t scrape them out with a knife.” I also like Joseph O’Connor’s image of “the quiet bomb”; and V.S. Pritchett’s phrase that they catch people “at bursting point”—there is definitely for me a feeling of a “breaking-out” from inside this controlled form. I like Colm Toibin’s image, too, of a story as a piece of music which gradually gathers and rises.

If I had to give my own definition? I think it would be a phrase I came across somewhere in the very un-short novels of Karl Ove Knausgaard. I spent last summer enthralled by his novels, and I can’t remember what he was talking about—it certainly wasn’t short stories—but he described something as being “a brief drama of the soul” and I loved that; I thought, yes, that’s what a short story is. It’s a brief drama of the soul—short stories are about our struggle to live and those words of Knausgaard’s convey to me that although a story might be brief it feels somehow huge: an enactment of a piece of a life that reaches into the past and into the future, deep inside us and beyond us.

16 May 2017 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.