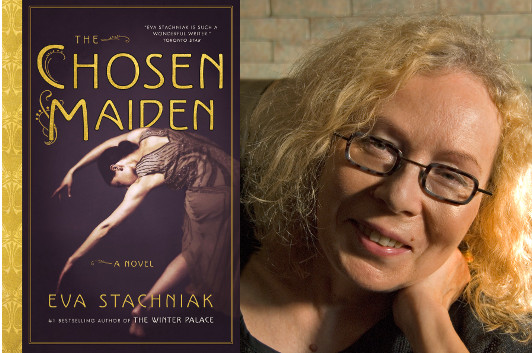

Eva Stachniak’s Fierce Power of Women

photo: StanisÅ‚aw Jerzmański

Eva Stachniak has written several novels, including The Winter Palace and Empress of the Night. Her latest, The Chosen Maiden, has just come out, and it vividly recreates the early life of Bronislava Nijinska, one of the great dancers of the 20th century. (You may have heard of her older brother, Vaslav Nijinsky.) In this essay, Stachniak explains what prompted her to take up Nijinska’s story… and how it ended up being a more personal story than she’d expected.

Having written two novels inspired by Catherine the Great, I wished to explore the time when Catherine’s legacy was coming to its violent end. This time it was not the Imperial court itself that attracted me, however, but the Artists of the Imperial Theatres, the stars of the Russian ballet. One of them was Bronislava (Bronia) Nijinska, a brilliant dancer and choreographer who came of age just as the Imperial Ballet, once an obedient and obliging child of the court, broke into open revolt and began to assert its own vision of what Russian art should become.

What drew me to Bronia? There was, of course, the tantalizing connection to her beloved elder brother, Vaslav, the God of the Dance (he was her mentor but she was the best interpreter of his choreography). There was the Polish connection (both Nijinsky parents came to Russia from Poland and Polish was Bronia’s mother tongue). There were her choreographic visions forged in the cauldron of revolutionary Russian art which secured her a firm place in the history of modern dance. But, in the end, as I pored over the treasures of the Bronislava Nijinska archives at the Library of Congress—boxes of intimate diaries, letters, and snapshots she took of her family and friends—the two main themes of The Chosen Maiden began to emerge: art as the source of inner strength and the steadfast solidarity of the Nijinsky women.

It was Bronia’s passionate belief in the power and importance of art that gave her strength to fight for her own place, first in the Imperial Theatres of St. Petersburg and then in the Ballets Russes where only men were groomed to be stars. Art gave her resilience to stand her ground when others told her she didn’t have the body of a ballerina or that she should content herself with preserving and interpreting her brother’s visions and not bother with her own. Art gave her the courage to resist the repressive regimes determined to engineer her soul. And, in the end, it was art that made her pick herself up after each paralyzing loss life dealt her and to keep on going.

Then there was the fierce power and loyalty of the Nijinsky women.

For as the men are erased from the family story, by choice or by the vagaries of fate, it is the women—Eleanora, Bronia, and Bronia’s daughter Irina; grandmother, mother, and daughter—who assume their place. Proud and strong, steadfast, nurturing and fiercely loyal, they stand by each other, even in the hardest of times. The world around them may be torn apart by wars and revolutionary upheavals, but they know that weakness is the luxury they do not have. The existence of their family depends on them.

Theirs is a story which most Eastern European families, including my own, know by heart.

And so as soon as the plot of The Chosen Maiden began to solidify in my mind, I found myself transported to the arms of the Polish women of my childhood, my own grandmother and mother. They too were brave, nurturing, tough as nails, stoic in their assessment of the dangers and possibilities of salvation, determined to wrench any chance they could from the little that they had. Born in what would one day be called the Bloodlands of Europe, between them they lived through two world wars, a revolution, a Nazi occupation and years of communist repression. Having experienced staggering losses, they still found a way to keep me safe and hopeful.

Pick yourself up and keep going. We’ve come through worse times and we didn’t give up. Resist when fighting is not possible. Remember, we are watching you.

Their voices are still in my head. And I’m still grateful for them.

13 February 2017 | guest authors |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.