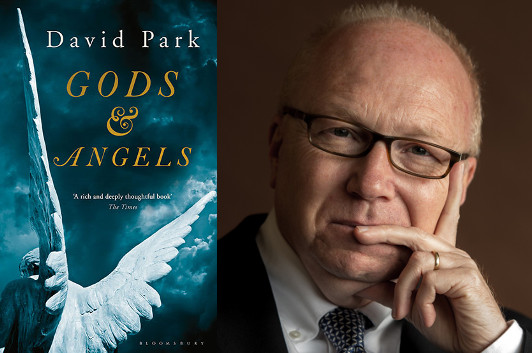

Life Stories #88: John Kaag

I spoke to John Kaag about his memoir, American Philosophy, shortly after the 2016 presidential election, so although we did spend a fair amount of time talking about his personal story, and how a rare book collection tucked away in an old building in the woods of New Hampshire helped Kaag make his way back from a profound, life-questioning despair, we also discussed what American philosophy can do to give solace to those of us who were shocked by what looked (and still looks) like the triumph of wrong over right, of evil over good. Philosophy, I think, offers us a guide to how we can live our lives, how we can best respond to the world around us, by getting in touch with what others have called “the better angels of our nature.” Kaag had some thoughts on that:

“One thing [philosophy] can do is to [help us] actually understand the gravity of the situation, so we can clarify how bad things actually are—and they’re bad. And William James actually had a good sense of this… James struggled with personal depression for most of his life, but he was also very touched by the political workings of imperialism, and James directly fought back against those forces.

I think that philosophy gives us a way of understanding what to do in the face of desperation or desolation. Sometimes Americans aren’t the best at this, but I’m thinking about Rilke. There’s this amazing story about Rilke in The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge… a story about a guy who’s facing utter desolation; he thinks that the world possibly is meaningless. But he also says if that is possible, it’s also possible that he himself, as an individual, might have the ability to do something about the meaninglessness. And I think that that’s actually a line that runs through American philosophy as well.”

Kaag also recommends essays by James and Henry David Thoreau as starting points for readers interested in what the American philosophical tradition, with its emphases on pragmatism and renewal, can tell us about how to move forward. And he hints at future writings on his part that might follow in those footsteps: “I think that there are lots of times in the history of philosophy where philosophers have had to stake a great deal on their thoughts, and I think that we might be entering one of these times,” he says. “I’m in the process of writing another sort of memoir like this one, but… it will have to be in some ways politically oriented, or socially oriented, because I think it’s wholly unacceptable for philosophers to ascend into the ivory tower when things are going really nasty.”

Listen to Life Stories #88: John Kaag (MP3 file); or download this file by right-clicking (Mac users, option-click). Or subscribe to Life Stories in iTunes, where you can catch up with earlier episodes and be alerted whenever a new one is released. (And if you are an iTunes subscriber, please consider rating and reviewing the podcast!)

photo: Rick Bern

18 January 2017 | life stories |

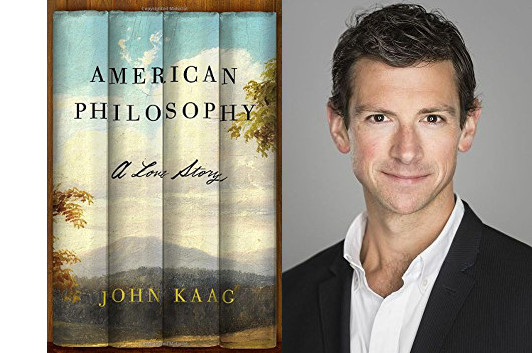

David Park’s Way of Seeing into Lives

photo: Bobbie Hanvey

As I was reading the stories in David Park’s Gods and Angels, I took note of the way he’s able to dig into the emotional lives of his protagonists, whether it’s a teenage boy who’s tired of having to spend the day after Christmas with his estranged (and clinically depressed) mother, or a middle-aged man who’s struggling, during a weekend getaway, to find a way to relate to one of his best mates (who’s also coping with depression). His stories take intriguing turns, like a university lecturer in Belfast who strikes up an uneasy friendship with some retired local toughs, or the retired schoolteacher on a remote (possibly Norwegian) island who uses Skype to keep in touch with his daughter, but they’re almost always rather subdued—less about the events that take place than about the characters’ responses to them. In this guest post, he explains how that approach is rooted in some of the writers he’s most admired.

Despite what others might say, it’s probably not possible to write a short story in Ireland without James Joyce metaphorically peering over your shoulder. In my case he’s actually there, because a small portrait I bought in a local auction hangs behind me on the wall of my writing room. It’s not a shrine and he competes with many other faces and images but I don’t doubt that the influence of his short stories in Dubliners has seeped permanently into my consciousness.

There is the exquisite portrayal of first love’s searing pain in a story like “Araby,” the climactic epiphany in “Eveline” where “all the seas of the world tumbled about her heart.” And of course above all there is the supremacy of “The Dead” that like a stone skims eternally across the creative consciousness and never sinks below the waves, no matter how much time passes or literary fashions come and go.

Beginning with the mundane details of a preparation for a party it moves to establish a social context, then gradually reveals the inner life of the central character until he experiences a life-changing moment that might be called self-knowledge, but in fact is more than this and something for which we have no ready name. The story is constantly rippling outwards until finally it encompasses the universal and time itself with the snow “falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead.”

12 January 2017 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.