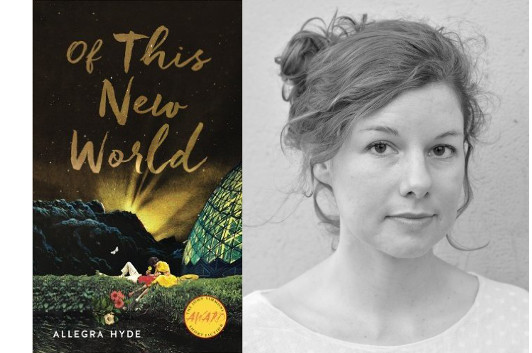

Allegra Hyde: The Beautiful Messiness of Deb Olin Unferth’s “Pet”

photo: Molly O’Keefe

I was delighted to learn that Allegra Hyde is a fan of Deb Olin Unferth, whom I’ve admired for years. And as I’ve been reading the stories in Hyde’s John Simmons Award-winning debut collection, Of This New World, I’m becoming a big fan of hers as well. Her stories have a strong knack for getting into the heads of emotional outcasts, like the teenage girl who’s extracted from her parents’ commune and sent to live with her grandmother in “Free Love” or the severely injured Iraq War vet obsessing over his twin brother’s encounter with his ex-girlfriend halfway around the world in “VFW Post 1492.” Like the Biblical Eve, who’s given a new voice in “After the Beginning,” Hyde’s characters have often jolted out of what should be a happy world, or walking in it but not quite able to make themselves of it, no matter how hard they strive.

I have owned many pets over the course of my life: a pet cat, a pet tree frog, a pet rock, pet Sea-Monkeys®. To quote George Eliot, “Animals are such agreeable friends—they ask no questions, they pass no criticism.” However, though our pets may ask no questions or criticize (at least most of them), they still reveal things about us in the way we interact with them.

Deb Olin Unferth knows this and uses it to great effect in “Pet,” which was originally published in Noon and later selected for the 35th Pushcart Prize collection. Among the many short story writers I admire, Unferth stands out for her ability to elegantly fuse scenes of daily existence with both humor and poignancy. In “Pet,” a woman’s son adopts a pair of turtles. The turtles must be cared for—which turns out to be rather strenuous. The ensuing turtle drama reveals the story’s deeper concern: the woman’s relationship with her son. Both narrative threads work in tandem, with the turtle problems speaking metaphorically to a struggling mother’s parenting efforts.

These two threads are conspicuously bridged in a climactic scene toward the end of the story. Here’s a passage from that scene that shows the stream of consciousness feeling to Unferth’s writing style, swaying and bending with the emotional movement of the protagonist:

So she goes and buys some drain cleaner, the really powerful stuff. She pours it in and waits (You didn’t mention the man, says her son, didn’t say a word. Well, she does have other concerns on her mind right now) and the drain explodes. Turtle feces all over the tub and wall and the curtain and the window because that is the kind of place she lives in with her only son, a basement apartment with cheap drains in a bad neighborhood because her husband divorced her and left, even through she stopped drinking, and he never calls his son, not even on his birthday, never sends enough money, and there is turtle shit on the wall and she has to be up early, and meanwhile years are going by, her son growing up and she fading further from his mind.

So here the story approaches a narrative peak in two ways: the turtle situation has escalated to the point of feces in the bathtub, and the mother-son situation has escalated to a disagreement over the mother’s romantic autonomy. Both situations present an ultimatum of sorts. Both are situations that cannot be ignored. Also noteworthy: the son-related thread initially appears as a parenthetical in the passage, inserted among the turtle stuff like an unwanted thought spearing into the protagonist’s mind. The use of this parenthetical emphasizes the way the two issues are explicitly coming together. The son situation butts against the turtle situation, both situations conspicuously running together, so that when the drain explodes we can sense that our protagonist’s relations with her son have also exploded (In the next paragraph the son says, “There is turtle shit everywhere… And you’re bringing home drunks,” a piece of dialogue that again explicitly unites these two threads). Along with descriptions of a literal mess in the above passage, our protagonist uses this passage to reveal the messiness of her life: the terrible ex, the drinking, the lack of money. Chaos is everywhere.

To speak a little more on Unferth’s prose style, this passage is also interesting with regards to its use of dependent clauses. In Virginia Tufte’s fabulous study of grammar, Artful Sentences: Syntax as Style, she points out that a dependent clause, when used correctly, “gives added weight, creates parallel rhythms and… a cadence.” Tufte gives examples come from political texts—texts meant to instill people with feeling, to move them—and it make sense that Unferth might want to move people at this moment in the story with a sentence that builds open itself, stacking up with misery and disaster. “Turtle feces all over the tub and wall and the curtain and the window,” she writes, then “a basement apartment with cheap drains in a bad neighborhood.” The story’s two primary interests compile here, but more importantly, they connect, fusing into a single notion of messiness.

I’ll add one last comment: Unferth’s short story collection, Wait Till You See Me Dance, is slated to come out in March 2017. No doubt it will be fantastic.

28 December 2016 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.