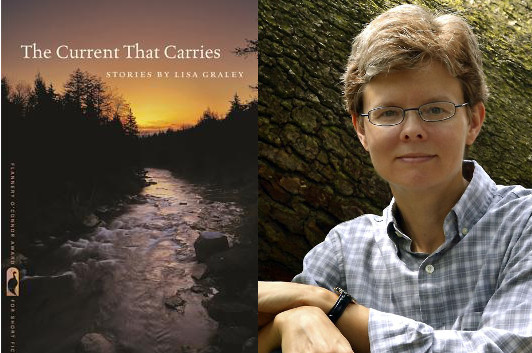

Lisa Graley: When Bad Things Happen to Good Characters

photo: Chelsea Ellison

Last year, the University of Georgia presented the Flannery O’Connor Prize to Lisa Graley for the short stories collected in The Current That Carries. One of the first things you’ll notice about Graley’s writing is her ability to get inside the heads of her characters, like the widower in “Vandalism” who starts out seeking payback against the joyriding teens who’ve been knocking over his mailbox but finds himself drawn into a much more complex emotional drama, or the narrator of “A Wild, to the Rim, Net or Nothing, Oven-Fired Ladling of Love,” reflecting on growing up in ’70s West Virginia, and how she and her grandmother formed an emotional bond watching Kentucky basketball star Kyle Macy. In many ways, Graley’s characters are defined by how to respond to crisis; in this essay, she reveals just how hard it is for her to put her characters in those situations…and how she’s learned to push through her resistance.

The first time I read Gabriel GarcÃa Márquez’s Love in the Time of Cholera and encountered Juvenal Urbino’s death, every thread of my readerly self cried, “Foul! You can’t kill the main character at the end of the first chapter!” I felt such attachment to the chess-playing, parrot-chasing, asparagas-urinating Doctor Urbino. I had invested so much. Hadn’t GarcÃa Márquez, as well?

It seemed as though Garcia Marquez had answered some kind of writer’s dare, loving and lingering over an adored character and then killing him so quickly. What audacity. What confidence.

Unlike Gárcia Márquez, I have a difficult time hurting my characters, much less killing them. Sure, I know pain is for their own good, and death, perhaps, good for some of their fellow characters. My hesitancy, I think, stems from a childhood where my brother and I played with toy guns but weren’t allowed to pretend-kill anyone. Aiming to maim was similarly discouraged.

Of course, characters aren’t people. But then again, they are. When you’re pulled into a story, you read to discover what happens to characters. You become involved—as if you were on an airplane hearing someone relate the true story of himself or herself or an acquaintance. When you’re writing, you tend to identify with characters the same way.

11 October 2016 | selling shorts |

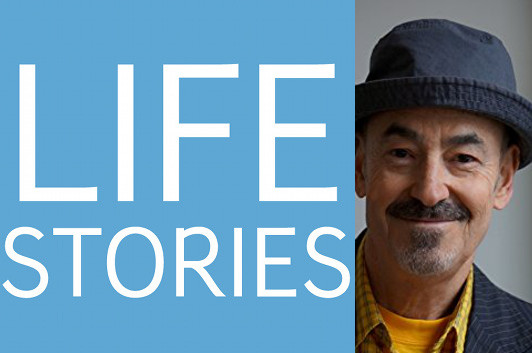

Life Stories #87: Barry Yourgrau

Barry Yourgrau actually lives just around the corner from me in Queens, so it was absurdly easy for us to get together to chat about his memoir, Mess—and the fact that this episode was recorded in my kitchen explains the occasional traffic noises from outside the second-floor window. Anyway, we had a great time talking about why he didn’t let anyone into his working studio—not even his girlfriend, whose apartment it was originally—and what happened when she finally told him to get it together. That led us to the differences between clutter and hoarding, and about how his efforts to create a document of his efforts to finally clear out his apartment sometimes created a “double block,” where he wasn’t writing and wasn’t cleaning. And then I mentioned how Mess foregrounds one of the fundamental qualities of memoir, the way in which it offers the memoirist’s life up for judgment, because that’s something Yourgrau does himself with practically everyone he encounters in the course of his story. Here’s what he said about that:

“To a certain extent, memoir is… people have doors which they—this is my room, don’t go in, a room of one’s own, right? So in a certain sense, a memoir opens that door. So for an artist to go into there is really difficult, a process of tremendous opening up vulnerability. But, on the other hand, the act of writing is a way of controlling.

Nobody’s memoir is the forensic truth… I mean, how many memoirs have you read where people remember conversations in their childhood? You tell me one person who remembers what they said in the kitchen to their mother. I mean, they may generally remember, but if they start offering you dialogue, it’s all constructed. Sometimes constructed with more veracity, sometimes constructed with less veracity…

For me, one of the things that’s interesting is that I’m usually a fiction writer, of, if I may say so, surreal fiction, but it’s surreal fiction like dreams, which means that it’s actually rather revelatory and confessional… I’m known kind of as a fantasist or something, but actually everything is—they’re all based on emotional events in my life that I dress up and change.”

Two collections of his early stories, Haunted Traveller (which is subtitled “An Imaginary Memoir”) and Wearing Dad’s Head, have just been reissued in paperback as well.

Listen to Life Stories #87: Barry Yourgrau (MP3 file); or download this file by right-clicking (Mac users, option-click). Or subscribe to Life Stories in iTunes, where you can catch up with earlier episodes and be alerted whenever a new one is released. (And if you are an iTunes subscriber, please consider rating and reviewing the podcast!)

photo: Charles Raben / Urban Face

5 October 2016 | life stories |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.