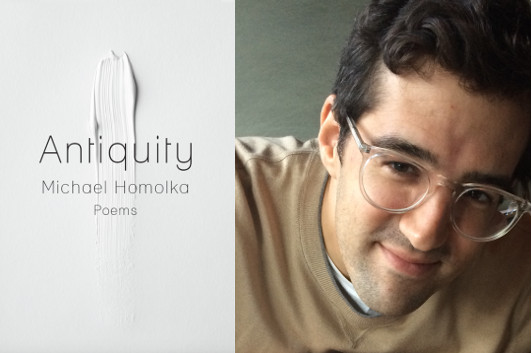

Michael Homolka’s Room Full of Rilke

photo:Tamara Arellano

Michael Homolka’s Antiquity is the recipient of the 2015 Kathryn A. Morton Prize for Poetry. (Longtime Beatrice readers may recognize the Morton Prize, as a previous winner, Jordan Zandi, shared his love for Szymborksa with us.) Homolka’s poems play with classical forms, sometimes reminding me of Stephen Burt, but always with an emotional tone that feels uniquely his own. In this guest essay, he talks about two poets who helped him find his voice.

Summer 2006. Bennington College MFA residency. A second story classroom with bugs and foliage out the window. Major Jackson finishes reading Rilke’s “You who never arrived” out loud to the group of ten students he and Timothy Liu are co-teaching, of which I am one:

And sometimes, in a shop, the mirrors

were still dizzy with your presence and, startled, gave back

my too-sudden image. Who knows? perhaps the same

bird echoed through both of us

yesterday, separate, in the evening…If it is said that poets traffic in silences, the silence in the room after that last word is equal parts deadly and transcendent. Major sums it up: “That’s a love poem, folks.”

I’m twenty-six years old at the time, ambitious to the point of hostility, jealous of every poet, jealous of every teacher. I’ve been working in book production in New York City for a few years; I go home every night and stay up until two or three in the morning revising drafts. So far I write only narrative poems. This June in Vermont marks the second of five residencies toward my degree.

It’s rare to see Tim Liu around campus without more books than he can reasonably carry, a conversation buddy or two, and the joy of literature written all over his face. He dances with students in groups when there’s music at night. He challenges others on the contents of lectures in his cargo shorts, hair flopping everywhere. I begin inwardly to refer to his way of being as “spiritual levity.”

What lingers in my brain just after Major’s reading are the more abstract fragments like “I have given up trying / to recognize you,” “the far-off, deeply-felt landscape,” and “all rise within me to mean / you, who forever elude me.” I don’t see it coming when Tim singles out “An open window / in a country house.” To my sensibility at the time, this is the most mundane detail—certainly one that didn’t need Rilke to write it.

…Must loss be sullied

by our need to love whatever survives?

Why give voice to any of that?…

How can Tim write lines like these (from For Dust Thou Art) yet bounce around campus lighter than helium, happy? What the hell makes Tim—Tim? I want to know. I ask him about halfway through the residency if he would like to go for a walk and talk poetry that afternoon after class, and he agrees. A few hours later we meet at one of the trailheads, wander for a while, and find a place to sit in the grass. He takes out all ten poems I brought for the workshop, and they are covered in pen. “You thought we were here to relax? No—we’re here to work.”

The statement comes out somehow warm and welcoming. The next 45 minutes sees him go through, poem by poem, and explain why he has crossed out more than two-thirds of the words on almost every page. Had I been Rilke, he would have crossed out all my you, who forever elude me’s and left only the open window[s] / in a country house. I don’t know what clicks at that moment, but my eyes are suddenly opened to the lyric power of concrete objects. Tim’s method and way of seeing becomes an addiction. Whenever I run into him the rest of the week, I show him my latest revision and hope that he’ll cross out less than he crossed out last time.

“This”—Major is searching for the word—“cutting.” He turns to Tim after Tim has salted the earth of another student’s poem and left only a few substantive lines. I’m not sure Major ever finishes the sentence, but it’s clear he wants to know what is behind Tim’s approach—and he wants the class to know too. “The poem moves by image,” Major has said once or twice over the course of the residency. From his collection, Leaving Saturn):

Johnny Cash had a love for transcendental

numbers & explained between puffs resembling

little gasps of air the link to all creation was

the mathematician…It doesn’t get more image than that. I have come to think of Major’s strategy as additive and investigative, and Tim’s as more subtractive, like a sculptor chiseling away excess. Tim answers, “I imagine each poem like you’re at a party. If there are too many people at the party, you can only ask people to leave. You can’t bring more.”

While Tim and Major co-taught for those ten days in Vermont, Major was my instructor by mail during the six months until the next residency (closing each correspondence “In art & life, Major J”). I ultimately found their approaches to revision two sides of the same coin. Major might isolate a few flattish lines from a poem and suggest I try to develop them more. I remember I wrote a poem that centered on some thoughts while walking. Major pointed out “the poem doesn’t feel like a walk.”

On the surface, revising according to Major’s approach would have meant examining why the poem didn’t feel like a walk, meditating on it, writing on it, and trying to develop the poem so that it did feel like a walk, whereas Tim’s approach would have entailed slashing the inauthentic lines to oblivion and then trying to transform the lyric energy with the remaining words. But it was never that simple. I almost always took Tim’s slashings and tried to replace them with lines he wouldn’t slash next time.

The air in the classroom felt tense sometimes as Major’s and Tim’s seemingly distinct approaches wavered side by side, gently sparring. There were those who were not receptive, and those who were. Then there was Rilke, too, of whose poems everyone in the class, at least for that day, could honestly say they are “all / the gardens I have ever gazed at.”

2 September 2016 | poets on poets |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.