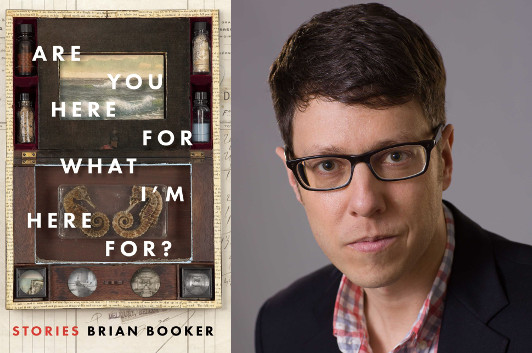

“A Little Something” Haunts Brian Booker

photo: Paul Crisanti

Disease and unease permeate the stories of Brian Booker‘s Are You Here For What I’m Here For? in equal measure. Sometimes, like in “A Drowning Accident” or “The Sleeping Sickness,” the two come together in eerie, unnerving ways, and even the stories where disease and illness don’t play a dominant role, like “Here to Watch Over Me,” take place in an atmosphere where the world feels just a little bit… off. In this guest essay, Booker talks about another short story where a long-buried secret continues to weigh on the present world, with increasingly disturbing results.

I like stories that make me complicit in their characters’ secrets. We often discover our characters’ deepest vulnerabilities by figuring out what they can’t or won’t say (or what others won’t say in their presence). We’re talking about the unspeakable, which means we’re talking about shame. Shame narratives concern trauma; the unspeakable revolves around a knot in the past, a piece of unfinished business that keeps us somehow stuck, dislocated, stumbling into the realms of the uncanny.

I feel I know the narrator in Dan Chaon’s story “Here’s a Little Something to Remember Me By.” Tom is thirty-six, married with two sons, and home for the holidays. His father has recently died and his mother now lives alone. This scenario is filled with precise evocations of the aches and recognitions of returning home, where the things you left behind are always still waiting for you. But what is really nagging at Tom about this visit are Mr. and Mrs. Ormson. The Ormsons want to see Tom, “just like always.” A worried curiosity has its claws in me.

Tom was the last person to see Ricky Ormson, his childhood friend, who went missing when they were fourteen. The case went cold decades ago. But the Ormsons, Ricky’s parents, “never gave up hope.” They adopted Tom as a kind of surrogate son, and have never let him out of the morbidly sentimental role they’ve curated for him. Obliged to spend an evening making small talk under “their soft magnetic gaze,” Tom senses “their sorrow, their rage, their anguish, all of it glided by murkily, like a shadow of something underwater.” They have decided, this particular year, to present Tom with a box of Ricky’s things. They are giving him something—another piece of the burden—but they also seem desperately to need something from Tom. What?

I think back to that phrase from the story’s first sentence, wanted to see me. It’s loaded, because Tom has become a hidden person—hidden to his family, his wife, even in some sense to himself. His hiddenness is the product of the secret Tom is carrying. Ricky has always been thought to have vanished, as it were, without a trace. But Tom knows more about what happened that day. He hesitates toward it through layers of memory scene. I won’t reveal “the secret” here—not because it’s a spoiler (it really isn’t), but because the content of the secret isn’t ultimately important. What matters is that Tom withheld information that might, or might not, have helped the police in their search for Ricky. It might have had some value for the Ormsons. Or it might have made things worse. What matters is that Tom kept his silence, and silence borne of shame has a snowballing effect: what starts out as “a little lie, probably not so vital,” bloats and crowds out other feelings, evolves into a self-absence that, for Tom, maybe “had ruined my life, in a kind of quiet way.”

What’s interesting in terms of dramatic structure is that Tom has confessed his secret—to himself, to the reader—by the story’s midpoint. In the hands of a lesser author, the story would evacuate its tension here. But the tension only builds. Now we know what’s really eating at Tom. But nobody else quite does. For a character with a guilty secret, anyone who walks onstage is a potential antagonist, any innocuous question a putative challenge. The atmosphere chafes with misreadings, with irony. The story holds us so claustrophobically in Tom’s point of view that we can’t see around him. Chaon makes us experience Tom’s obsession as if it were our own.

Deep down, perhaps, Tom wants to confess everything. Because here’s the elegant counterpoint in characters motivated by shame, who move through the world feeling like actors or fakes: they fear being seen through, yet they yearn to be seen for who they are. That’s the only way to love and wholeness. We know the emotional stakes, for Tom, couldn’t be higher. But we don’t know what the consequences of exposure would be. And we don’t know what Tom—’by accident or by choice—is going to do.

7 August 2016 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.