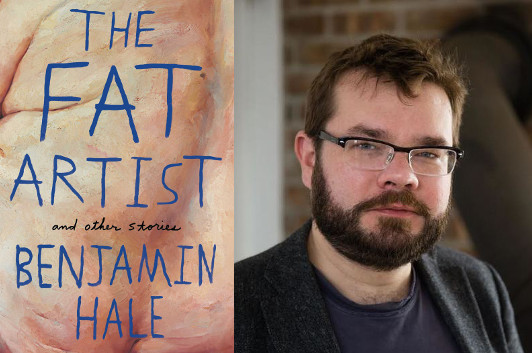

Benjamin Hale & “A Game of Clue”

photo: Pete Mauney

I liked Benjamin Hale‘s The Evolution of Bruno Littlemore, which I reviewed for Shelf Awareness, and I was eager to see what he’d do next. After all, a nigh-Nabakovian novel narrated by an intelligent chimpanzee is a hard act to follow—but The Fat Artist and Other Stories doesn’t disappoint. These stories are more naturalistic… well, okay, “The Fat Artist” exists in that twilight zone between absurdism and science fiction that Robert Sheckley used to detail so masterfully. But there are other great stories in here, like “If I Had Possession Over Judgment Day” or “Leftovers,” that take place in a world as real as real could be, even when events go to their most extreme. One of the things I particularly enjoy about this collection is that Hale gives his stories room to play out; it’s something he talks about in this guest post, in the context of one of his own favorite stories.

Steven Millhauser is one of two writers of whom I can say this: Whenever he publishes a new book, I drop whatever else I’m doing and immediately buy it and read it. (The other is Nicholson Baker.) I discovered Millhauser’s fiction in my early twenties, when someone recommended I read his first novel, Edwin Mullhouse: The Life and Death of an American Writer, 1943-1954, by Jeffery Cartwright. The local bookstore didn’t have it, but they did have The King in the Tree, a collection of three novellas that had just come out. I bought it, took it home, and within a few pages I was beginning to understand that I had opened the work of a writer who spoke directly and with rather uncanny precision to me, who clearly derived the same sort of pleasures from literature as I do.

In Millhauser, I found a very American writer who crafts Borgesian structures out of Nabokovian wit and wordplay, with as much humor and perhaps even more humanity than either Borges or Nabokov. Later, I did read Edwin Mullhouse (I hate hyperbole, but I consider that book to be one of a handful I can think of by living writers that I would call a “masterpiece”), and the rest of his published fiction, too.

Millhauser is a master of both long and short-form prose fiction, as well as a hybrid animal, the longish story/shortish novella. This might be my personal favorite form for prose fiction—both to read and to write. (The Fat Artist contains just seven stories, all of them on the long side, and a few of which are novella-length.) “The problem with stories,” I once heard Charles D’Ambrosio say, “is that they have to be efficient. Stories that aren’t efficient are novels.”

9 August 2016 | selling shorts |

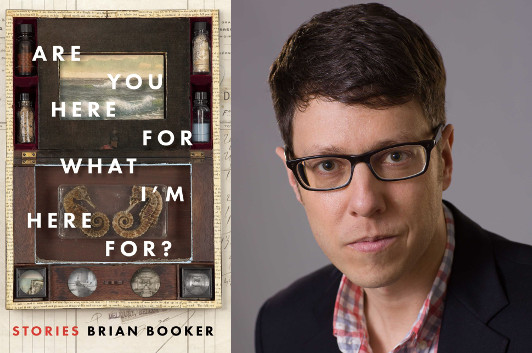

“A Little Something” Haunts Brian Booker

photo: Paul Crisanti

Disease and unease permeate the stories of Brian Booker‘s Are You Here For What I’m Here For? in equal measure. Sometimes, like in “A Drowning Accident” or “The Sleeping Sickness,” the two come together in eerie, unnerving ways, and even the stories where disease and illness don’t play a dominant role, like “Here to Watch Over Me,” take place in an atmosphere where the world feels just a little bit… off. In this guest essay, Booker talks about another short story where a long-buried secret continues to weigh on the present world, with increasingly disturbing results.

I like stories that make me complicit in their characters’ secrets. We often discover our characters’ deepest vulnerabilities by figuring out what they can’t or won’t say (or what others won’t say in their presence). We’re talking about the unspeakable, which means we’re talking about shame. Shame narratives concern trauma; the unspeakable revolves around a knot in the past, a piece of unfinished business that keeps us somehow stuck, dislocated, stumbling into the realms of the uncanny.

I feel I know the narrator in Dan Chaon’s story “Here’s a Little Something to Remember Me By.” Tom is thirty-six, married with two sons, and home for the holidays. His father has recently died and his mother now lives alone. This scenario is filled with precise evocations of the aches and recognitions of returning home, where the things you left behind are always still waiting for you. But what is really nagging at Tom about this visit are Mr. and Mrs. Ormson. The Ormsons want to see Tom, “just like always.” A worried curiosity has its claws in me.

Tom was the last person to see Ricky Ormson, his childhood friend, who went missing when they were fourteen. The case went cold decades ago. But the Ormsons, Ricky’s parents, “never gave up hope.” They adopted Tom as a kind of surrogate son, and have never let him out of the morbidly sentimental role they’ve curated for him. Obliged to spend an evening making small talk under “their soft magnetic gaze,” Tom senses “their sorrow, their rage, their anguish, all of it glided by murkily, like a shadow of something underwater.” They have decided, this particular year, to present Tom with a box of Ricky’s things. They are giving him something—another piece of the burden—but they also seem desperately to need something from Tom. What?

7 August 2016 | selling shorts |

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.

Our Endless and Proper Work is my new book with Belt Publishing about starting (and sticking to) a productive writing practice.